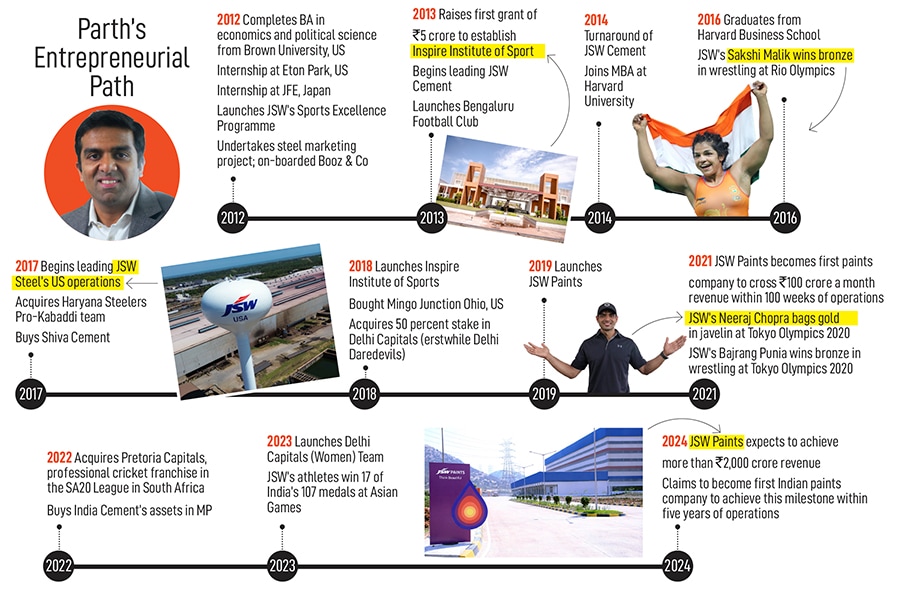

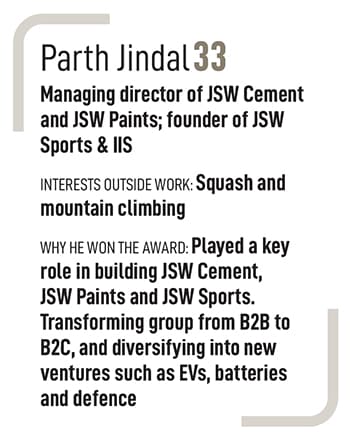

Parth Jindal and the making of an institution of the future

Third-generation entrepreneur Parth Jindal displays nerves of steel, makes concrete plans to create brands out of commodities, and gives JSW Group a sporting makeover with a fresh lick of paint

Parth Jindal, MD, JSW Cement and JSW Paints and founder of JSW Sports & IIS

Image: Nayan Shah for Forbes India

Parth Jindal, MD, JSW Cement and JSW Paints and founder of JSW Sports & IIS

Image: Nayan Shah for Forbes India

Early 2018. Mumbai. Three big guys were seated comfortably at the lunch table. On one of the middling afternoons in February, Sajjan Jindal, Seshagiri Rao and Jayant Acharya huddled for the mid-day meal, which the trio had been having together for years. Usually, the afternoon spread was also the time when the three—group chairman of JSW Group, group CFO and joint managing director and CEO of JSW Steel, respectively—would have something else on their plate: A quick informal, mini update on top business developments.

This Friday, uncharacteristically, the food had taken a back seat, and the mood had turned slightly pensive. “Let us bid higher for Bhushan Steel,” stressed Sajjan, founder of the diversified steel-to-cement-to-energy conglomerate. There was a note of urgency in the voice of the second-generation entrepreneur who started his career with a steel plant in 1982, and over the next few decades, JSW Steel emerged as the biggest steelmaker in the country under his captaincy. Back at the lunch table, he was busy making plans to snap up Bhushan Steel, which was under corporate insolvency resolution process, and on the radar of Tata Steel, which was one of the bidders to acquire the distressed asset. Acharya reckoned the bidding might be a photo finish.

The prospects of a close call made Jindal up the ante. “We just can’t lose that. Raise the bid and let’s be aggressive,” he underlined. Rao, meanwhile, slipped in another query. “Sir, what about Bhushan Power and Steel? What should we do?” the CFO asked, alluding to the impending deadline to submit bids for another bankrupt steel company in Odisha.

A few seconds later, a bold voice interjected the conversation. “Dad, I hate to tell you this, but I don’t think we are going to get Bhushan Steel,” underlined Parth Jindal, the third- generation entrepreneur who graduated from Brown University in the US, worked at a hedge fund in New York for six months, had another quick stint at JFE Steel, Japan’s second largest steel maker, and finally joined the family business in 2012.

Junior Jindal continued with his pitch. “Bhushan Steel is going to go somewhere else, dad,” he said, and offered another plan of action. “We must buy Bhushan Power and Steel,” he underscored, elaborating on the reasons for making a contrarian bet. “If the Tatas are entering our territory—south and west India—then we have to go into theirs, which is east India,” he argued. “We must buy this.” The patriarch was stunned as well as impressed.

Junior Jindal continued with his pitch. “Bhushan Steel is going to go somewhere else, dad,” he said, and offered another plan of action. “We must buy Bhushan Power and Steel,” he underscored, elaborating on the reasons for making a contrarian bet. “If the Tatas are entering our territory—south and west India—then we have to go into theirs, which is east India,” he argued. “We must buy this.” The patriarch was stunned as well as impressed.