Bagrry's: Cereal killer

The homegrown company has battled MNC giants like PepsiCo to become India's second-biggest breakfast-cereal maker after Kellogg's

Shyam Bagri does not wish to dilute stake in Bagrry’s or sell out. His son Aditya (right) says the company is in sync with the Indian palate

Shyam Bagri does not wish to dilute stake in Bagrry’s or sell out. His son Aditya (right) says the company is in sync with the Indian palate

Image: Amit Verma

Sometimes a single letter in a word that’s moved around can prove a masterstroke. Like it did for the UK-headquartered fashion clothing brand French Connection, which had its tryst with fame with the FCUK logo during the early ’90s.

Sometimes, though, a single letter in a word can also spell disaster. Like it did for entrepreneur Shyam Bagri, 59, in the early 2000s.

Bagri’s flagship product muesli—a mixture of whole grains, nuts, fruit, berries—was being confused with musli, an aphrodisiac. Consequently, consumers shunned the alien-sounding breakfast cereal product. Bagri’s company Bagrry’s—which could be construed as a metaplasm, or a deliberate misspelling (of Bagri’s name) to give a word a new meaning—in spite of being the first one to launch muesli in India, was losing out to cornflakes.

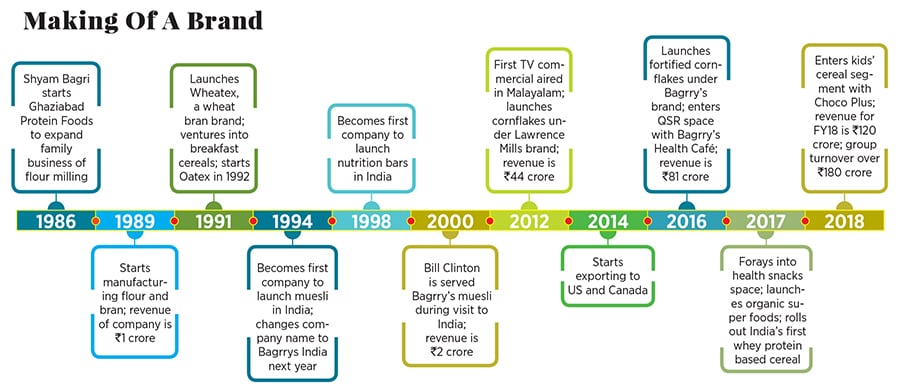

“Both the words not only looked alike but were also pronounced erroneously in a similar way,” rues the Delhi-based second-generation entrepreneur, who launched the Bagrry’s brand of breakfast cereals in 1994. “People knew cornflakes, but muesli had few takers.” That the then US President Bill Clinton was served Bagrry’s muesli during his visit to India in 2000 was of little help in making the cereal popular. What also hurt the brand was the absence of cornflakes from its product portfolio.

The gritty businessman was quick to find a way out: A new pack, a new name—Healthy Crunch—and a new positioning. “The point size of the word muesli was reduced considerably and the word itself was removed from the centre of the pack,” Bagri recounts.

“Bagrry’s is an innovative venture that created a niche for itself against MNC competition,” says brand strategist Harish Bijoor. Like Haldiram’s, Bagrry’s took the family name and ventured out to make a brand of it.

WHEN SMALL IS A BIG PLUS

Although Bagrry’s could never make the most of its first-mover advantage, it has been able to piggyback on the expansion of the market by the MNCs. What could have been Bagrry’s biggest weakness—lack of financial muscle—turned out to be its biggest blessing.

“Our marketing and advertising expenses were minuscule compared to those of the MNCs. This helped us sail through,” grins Bagri, who reckons that deep-pocketed rivals like Kellogg’s and PepsiCo helped the company grow. The nascent breakfast cereal market, he lets on, got a big push in terms of brand awareness and consumer acceptability due to the advertising and marketing blitzkrieg of giants like Kellogg’s. “Educating people was our biggest challenge due to paucity of marketing budgets,” he concedes.

What’s more, packaging, which once threatened to singe Bagrry’s due to the protruding logo of muesli, turned out to be biggest brand-building and awareness tool. Bagri started inserting listicles inside the packs, educating consumers about oat, muesli and bran. The rear of the packs too had information on muesli and oats. “Listicles and packaging made us more familiar, acceptable and increased our reach,” contends Bagri, who traces his roots to Rajasthan.

“As an Indian company, we are more in sync with the Indian palate, and understand what works and what does not,” avers Aditya Bagri, the 29-year-old son of Shyam Bagri. The third generation entrepreneur (Shyam Bagri’s father had founded a flour milling venture in the ’50s) explains how. When Bagrry’s started making oats in early 2000, it shifted its packaging from a tin to a glass jar. The move, claims Aditya, was based on consumer insight. Indian homemakers see more value in jars than tins because they can be reused and preserve products better.

What also came in handy during the initial phase of struggle was the support from Ghaziabad Protein Foods, the company started by Bagri to expand the family business of flour milling in 1986. After five years, Bagri diversified from the wholesale business to consumer retail by rolling out wheat bran brand Wheatex in 1991. A year later, Oatex, a processed oats brand, was launched. In 1994, the name of the company was changed to Bagrrys India, and the wholesale business became the B2B vertical of the parent group.

Over the next decade, the B2B division started supplying raw materials to big MNC brands. For instance, Nestlé. Apart from being the sole supplier of oat flour for Maggi oat noodles, Baggrys India sells refined wheat flour for Maggi instant noodles, and oat flour for baby food brand Cerelac. The B2B division, which now contributes over ₹60 crore to the group revenue, also has other notable clients. Yum! Brands uses specialised wheat flour of Bagrrys India for KFC products; ITC takes oats for Aashirwad Multigrain Atta and Sunfeast biscuits; and wheat bran is a specialised ingredient in Dunkin’ Donuts burger.

The cushion provided by the B2B vertical also helped Bagri in dealing with a moral dilemma which always tormented him: A trade-off between the ethical (dealing in healthy foods) and the pragmatic (revenue and profits).

Bagri’s first moral predicament was in 2000. Revenue had crawled from ₹1 crore in 1989 to ₹2 crore in 2000, and demand for muesli stayed muted. Driving the market was cornflakes,

a category missing in Bagrry’s arsenal. Reason: Cornflakes have a high Glycemic index—a relative ranking of carbohydrates in foods—which means that they release glucose rapidly. Moreover, cornflakes lack fibre. For a company that started with wheat bran and processed oats, cornflakes was a taboo.

The business reality and market dynamics, however, made Bagri bite the bullet. Bagrry’s cornflakes, along with refined flour (maida), were launched in early 2000.

Though launched with much fanfare, Bagri stopped selling cornflakes after a year. “Cornflakes and refined flour were clashing with the ethos of the company,” he explains. While muesli and bran helped in lowering cholesterol— they have a lot of fibre and are hence healthier—cornflakes were just the antithesis. “We stopped cornflakes and decided to focus only on muesli and oats,” he recounts.

Bagrry’s has grown from ₹2 crore in revenue in 2000 into a ₹120-crore brand. It’s present in 70,000 retail outlets in India

While Bagri made peace with his ‘guilty conscience’, his business side started haunting again after a decade. In spite of all efforts to push muesli and oats, cornflakes were still driving the market and a slew of MNC and local players was making the most of it.

Bagri had no option but to relaunch cornflakes in 2012, this time under the Lawrence Mills brand. The move helped company gain financial heft as sales boomed. Lawrence Mills, which is now a ₹10 crore brand, also helped Bagrry’s in penetrating smaller towns with its economical pricing. Bagri though wasn’t a happy man. “While discontinuing cornflakes was the right decision, restarting it after a long gap of 10 years was probably a mistake,” Bagri avers.

To make amends, Bagrry’s launched cornflakes under Cornflakes Plus after four years in 2016 with the entrepreneur doing his best to make the product ‘healthy’. Fructose and wheat fibre were blended with cornflakes. “We use natural antioxidants as compared to synthetic ones used by others,” claims Bagri. “While Lawrence Mills arose to cater to the demands of the market, Cornflakes Plus arose from our conscience to sell a healthy product.”

Though Bagri has survived odds, the going won’t be easy. The biggest challenge still remains the same: Wide acceptance. Muesli and oat are largely confined to urban India, which has over the last few years seen many other breakfast options, including ready-to-cook breakfast mixes.

“Most Indians still prefer a ‘hot’ breakfast. Ready-to-cook breakfast mixes such as upma and dosa would be Bagrry’s biggest competitor,” contends Ashita Aggarwal, marketing professor at SP Jain Institute of Management and Research. “Saffola oats and Kellogg’s cornflakes, and now muesli, are aggressively wooing consumers.” The real challenge, however, lies in continuously innovating to keep itself differentiated on the health plank. “The breakfast cereal market is ruthlessly competitive. While innovations might take time, deep-pocketed rivals can disrupt the segment,” reckons Aggarwal.

In spite of umpteen acquisition proposals, Bagri is in no mood to either dilute stake or sell out. “The namkeen land of India (Rajasthan) also has a healthy brand: Bagrry’s,” he smiles.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)