Venture Catalysts: Scouting for angels

India's biggest early-stage startup investment firm is looking for them across smaller towns, even as the segment enters a phase of a prolonged funding freeze

“ We have been democratising early-stage investment by roping in investors from smaller towns and cities. And the gambit has paid off handsomely”

Apoorv Ranjan Sharma, co-founder of Venture Catalysts

As a startup evangelist, Divya Pritwani has his task cut out. The easy part is talking about the cause. The tougher part is getting people to support his mission. “Why should I invest in startups when I know it’s a disproportionately high-risk game,” argues Kushal Vaswani, director of Raipur-based steel manufacturer Vaswani Industries. The death rate among startups globally, including India, is more than 90 percent. Vaswani, 30, has seen enough fickleness in his listed company over the last decade to try his luck in the startup world.

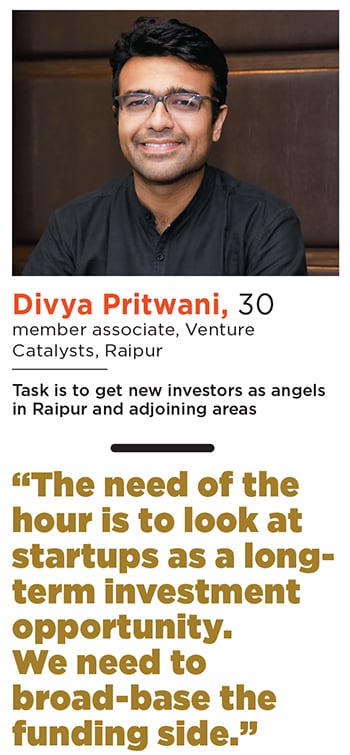

“Are startups not too hyped?” the second-generation entrepreneur lobs another query at Pritwani, host of an informal meeting at Courtyard by Marriott in Raipur in early December. His agenda is to hunt for potential angel investors in smaller towns and cities. “I would rather play safe than flirt with high risk,” avers Vaswani. Pritwani retorts: “You have to play the game to hit a jackpot.” The rewards, he grins, are equally disproportionate. The need of the hour, he lets on, is to look at startups as a long-term investment opportunity rather than a gamble. With the momentum of venture capital (VC) exits gathering pace in India—$4 billion worth of exits in 2017, which skyrocketed to $20 billion, largely because of the Flipkart buyout in September 2018—this is the right time to jump in. “The sooner one gets in, the better,” says Pritwani, a member of Venture Catalysts, India’s largest early-stage startup investment firm. Vaswani ponders. “No harm exploring,” he mutters, as Pritwani manages to seed the idea.

Cut to Dehradun. Apoorv Ranjan Sharma, co-founder of Venture Catalysts, is addressing a group of Uttarakhand investors, exhorting them to invest in startups as angels. “Look at Adurcup,” he says during his Masterclass in December. As he elaborates on the positives of the startup, which works with hotels, restaurants and caterers, the audience learns about the business model and dynamics of the Delhi-based online restaurant procurement platform. After the Masterclass—a session to pitch startups to potential angel investors across tier II and III towns—Adurcup manages to raise $500,000 from a bunch of investors in Dehradun.

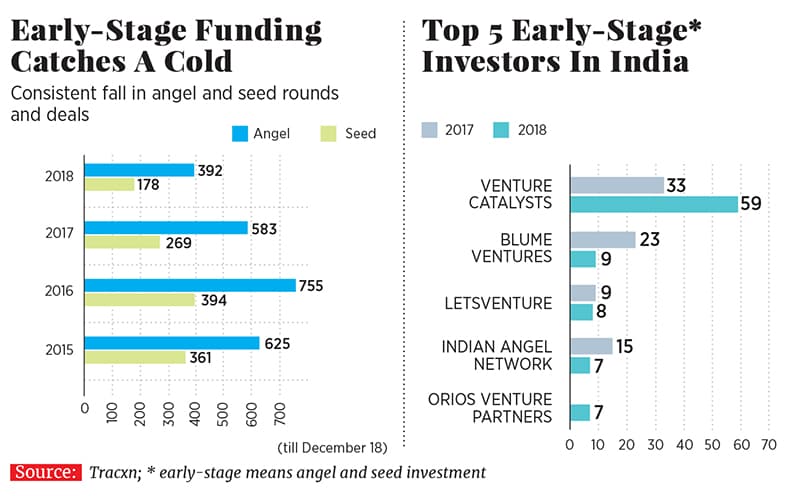

In spite of a steady fall in volume of early-stage deals in India over the last three years, Venture Catalysts, which typically invests ₹2 crore to ₹7 crore in startups, has managed to grow manifold. From ₹15.6 crore invested in startups in 2016, Venture Catalysts has leapfrogged funding to ₹172 crore in 2018. The number of deals jumped from 12 to 59 over the same period.

Contrast this with the overall early-stage deal scenario, and you see how tier II and III towns have helped Venture Catalysts trump the industry. From 361 rounds of angel funding in 2016, the number dipped to 178 till December 18, 2018, according to data from Tracxn, a startup data platform. Seed rounds, which typically follow angel rounds, too, have fallen by over 40 percent, from 625 to 392 during the same period. In fact, the total deals logged by Venture Catalysts this year are more than what the next nine players could manage collectively. The magic clearly has been the small-town push.

WHEN SMALL IS BIG

Over 60 percent of investors in Venture Catalysts are from tier II and III towns. From a mere 821 investors in 2016—most from tier I cities—the Mumbai-based early stage investment firm has taken its investor count to 3,647 as of mid-December 2018.

Success stories of startups from smaller cities have played a massive role in boosting the sentiments of local investors. Take, for instance, Ahmedabad-based fintech firm Lendingkart. Investors such as Singapore’s Fullerton Financial Holdings reportedly pumped in $87 million in Lendingkart in one of the biggest deals outside the main metros in 2018. Ahmedabad, Pune and Surat attracted the most investments during the first nine months of 2018—$183 million collectively. Yet another data point from Tracxn suggests that companies from over 25 smaller cities such as Guwahati and Thiruvananthapuram bagged $293 million collectively from investors during the same period.

Adding to the push is the mushrooming of incubators and accelerators across such towns. Out of more than 210 active incubators and accelerators in 2018, over 38 percent were based in tier II and III towns. “Chances of getting funded increases three times for a startup after becoming a part of an incubator or accelerator,” says the report.

Back in India, there is another strong parallel trend that explains Venture Catalysts’s success in smaller towns. Mutual fund investments, which had largely been confined to the top cities, have been silently undergoing a tectonic shift over the last few years. The country’s smaller towns or B30 (beyond top 30 cities) locations accounted for 14.7 percent of the industry’s total assets under management (AUM) by end of September 2018. Contrast this with the 7 to 8 percent contribution a decade ago. According to the latest CII Mutual Fund Sector report, B30 cities may register much faster growth at 25 to 30 percent, and could potentially contribute 25 to 30 percent of the AUM mix by 2023.

“It’s all about exposure and awareness,” says Sharma of Venture Catalysts. What happened with mutual funds, he asserts, is happening with angel investment now: Democratisation of the investor base.

EXITS BRING MATURITY

In Raipur, Brijesh Thakkar, chief investments officer at Chhattisgarh Investments Limited, a holding company of Sarda Energy & Minerals, reckons that the maturing of the startup ecosystem also nudged smaller investors to turn angel. Thakkar brandishes some numbers to buttress his contention. VC investors in India, he quotes a recent report by Bain and Company and Indian Venture Capital Association, recorded a fourfold rise in exits during the first nine months of 2018: $19.6 billion compared to $4.2 billion a year earlier. Exits are expected to increase, with nearly 80 percent of startup founders expecting investor exits by 2024, says the report.

In spite of the fact that the $16 billion Walmart-Flipkart deal contributed around 80 percent to the exits in 2018, Thakkar is optimistic. “It’s all about sentiment,” he says. “Investing through a specialised body is different from individual investment,” adds Thakkar, who made his first angel investment three years ago and has since then invested in a slew of startups through Venture Catalysts. Angel investment, he says, is no longer ‘spray and pray’ as it used to be. With the startup ecosystem developing in smaller cities, more people are likely to turn angel, he adds. “Startups have grown as an asset class,” he says. Conceding that there are bound to be misses, Thakkar maintains that the risk that comes with startups is similar to that of equity markets. “It all depends on your risk appetite.”

For Sharma of Venture Catalysts, the love affair with smaller towns and angel investing started with the jackpot he hit in mid-2016. Japanese internet and telecom major SoftBank had led a new round of funding in budget hotels startup Oyo Rooms. The amount invested was reportedly ₹413 crore. During the same period Oyo Rooms bought back shares worth ₹60 crore from its early angel investors, led by VentureNursery. The Mumbai-based accelerator had invested about ₹25 lakh in the company in 2012, and reportedly raked in returns of about 250 times.

“Oyo is my biggest success story,” grins Sharma, who was one of the co-founders of VentureNursery. “This made me realise that gold lies in smaller towns, their entrepreneurs and investors,” adds Sharma, who explains why the untapped opportunity in tier II, III and beyond is a blessing for his venture. Smaller cities like Jaipur, Raipur and Jamshedpur are likely to have over 23 percent of high net worth individuals, with a net worth of ₹25 crore and above by 2020-21, according to the Top of the Pyramid report by Kotak Wealth Management.

Angel groups are realising the big opportunity outside top cities. “Opening up a wider base is enabling more investors to explore this asset class,” says Anil Joshi, founder and managing partner at Unicorn India Ventures. “Once established, it will certainly open doors to local startups and reduce dependency on the metros.” Though it would be too early to say if this trend would democratise angel investments, involvement of angel groups is certainly playing a crucial role in educating potential investors, Joshi adds.

Meanwhile in Ranchi, Anupam Tyagi is getting ready to turn angel. Tyagi, who runs an iron ore transportation business, is interested in local agri-startups focussed on mushroom cultivation and silk. “The next unicorns are going to be out of such cities. So it’s always better to catch them early,” says Tyagi, who has created a kitty of ₹50 lakh for startup investments. On his wish list, though, are Zomato and Swiggy. But he’s also a realist. “I know I can’t get a finger into those pies,” he smiles. In its latest ranking of states by the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion, Jharkhand was ranked as an aspiring leader in developing a startup ecosystem, along with Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, and Uttar Pradesh.

The bet on tier II and beyond, though, comes with risks and challenges. The biggest one is of handling the new angels. “If they are not nurtured properly, it could prove to be counter-productive,” warns Joshi of Unicorn India Ventures. Onboarding uninformed angel investors could lead to dissatisfaction among them; confusion about angel tax might also be a deterrent.

Sharma prefers to look at the brighter side. “The opportunity to trigger an angel revolution across the country is massive,” he says. He adds that his Masterclasses are aimed at not only getting new angels but also educating them about startups, as he gets ready to head to Lucknow and Kanpur.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X