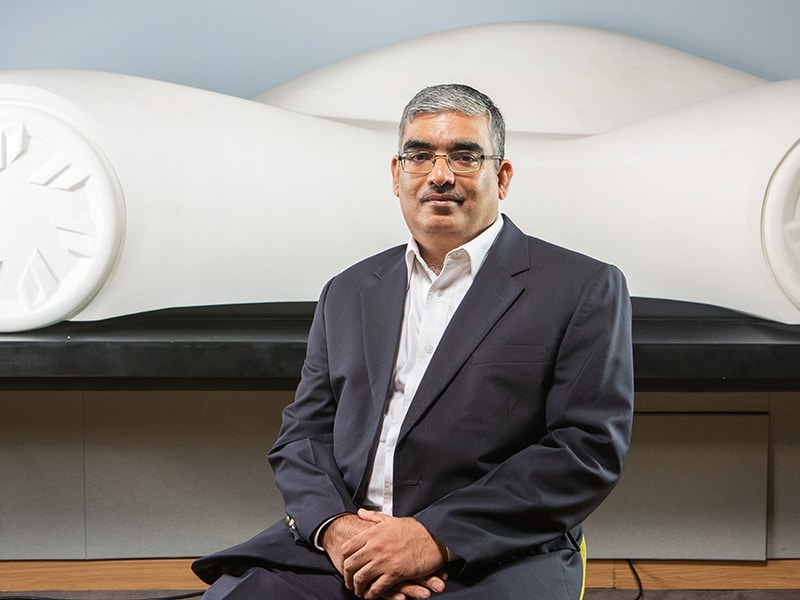

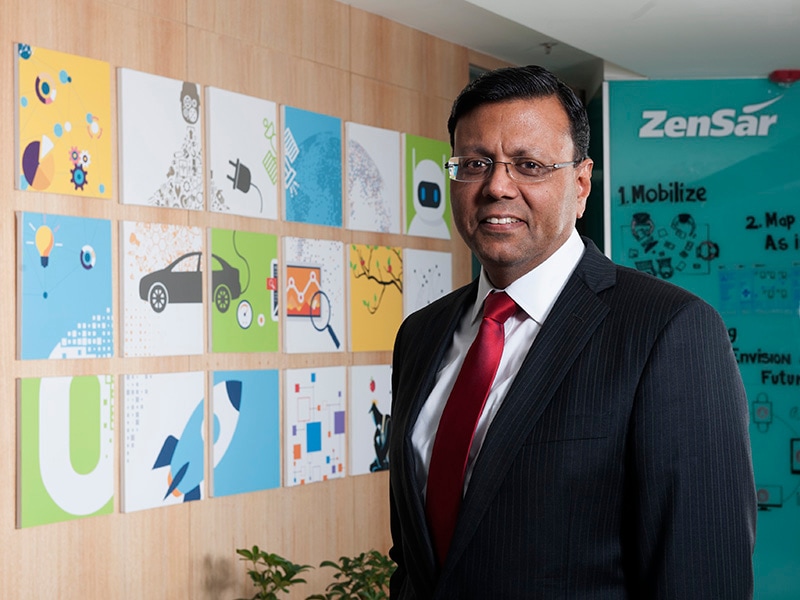

Tata Motors is prepared to play in the electric market: Guenter Butschek

Tata Motors' business head Guenter Butsche

Tata Motors' business head Guenter ButscheGuenter Butschek heads Tata Motors' businesses worldwide, except Jaguar and Land Rover. His focus, since getting appointed as the CEO and managing director in 2016, has been to bring flexibility in taking vehicles to a dynamic market. In 2018-19, Tata Motors sold almost 6.8 lakh vehicles—16 percent over the previous fiscal even as the Indian market became sluggish. In this interview with Forbes India, Butschek explains how the Rs 301,938-crore automaker grew in India, while navigating changes in technology and moving to Bharat Stage (BS) VI regulations for cleaner vehicle emissions.

Q. Tata Motors actually grew its volumes in what was a tough financial year for the industry. What contributed to the positive performance?

It was our best year in the past decade. The foundation was largely put in place in the first half of FY19, where at least commercial vehicles (CV) performed strongly across a range of products. In passenger vehicles (PV), the first quarter was an exceptionally good one, but we saw weaknesses towards the end of second quarter [September 2018] in particular. This was during the beginning of the NBFC (non-banking financial companies) crisis—and the consequent constraints on liquidity.

The second half of the fiscal year did turn out to be a challenge, but not to the extent that it wiped out the strong first half. It gave us a good indication that the industry might not grow as per initial expectations, and that we would face significant structural challenges in PV as well as CV for different reasons.

Q. What transpired in the 2020 fiscal?

In the first quarter, we consistently asked ourselves every month if the problem had bottomed out. Was the worst behind us? Until July, the market got worse. It came as a surprise, though the first signs of subdued demand were visible in late 2018—first in commercial, then cargo and construction.

There is a certain seasonality in the Indian market—the first quarter is normally not that strong; the second quarter sees lower demand; the third quarter is the festive season, and the fourth quarter tends to be strong. But none of these patterns played out in FY20. The first two quarters of 2019-20 were an escalation of the problem because the entire industry started taking action. The keyword became block closure—the reduction in (production) capacity and wholesale—because if retail sales aren’t happening and the dealers are short on funding, they will not be able to replenish stocks. This brings the whole working-capital cycle to a standstill.

The whole ecosystem is very sensitive to our capacity planning [In the quarter ended September 2019, Tata Motors reduced stock by Rs 3,400 crore as wholesale declined to 106,349 units]. On the one hand, we have to be aligned with the dealers, and the suppliers on the other. The impact has been huge even for our partners in the value chain. It [market slump] was a serious problem.

Q. So how are you looking to invest for the future while navigating such extreme conditions of the present?

We have to make sure that the way we attack the present problem doesn’t compromise our future. While we hope the next quarters bring change, a single quarter doesn’t change our strategic plan. If these conditions last for a year, it may require a review of our future plans. So far, we have had a strong commitment from the management, reinforced by our Board of Directors. We don’t compromise on the future.

We have started a product offensive. Product launches are a part of a larger play for a profitable core strategy to turn PV as well as CV into substantial cash-accretive businesses. There is a large play around the products at Tata Motors, which goes into culture, people, structure, processes—and the entire value chain. Tata Motors has seen Turnaround 1.0 and Turnaround 2.0, and while external conditions have deteriorated, we believe that we have been able to change our culture. We have brought speed, simplicity and agility to Tata Motors. These are the key ingredients to manage the present challenges and future, decisively and sustainably. The strategic agenda is intact.

Q. What is the portfolio plan for Tata Motors, considering there is competition from technology companies in cab-aggregation, autonomous cars and electric mobility?

We generally call such competition as disruption, which is three-fold—technology, business models and partnerships. As far as technology is concerned, Tata Motors has a strategic technology roadmap. Our product portfolio is well synchronised with and anchored to our strategies for both CVs and PVs. It is also well-synchronised with our vertical for (vehicle) electrification and electric mobility. Technology is just one approach to leverage the market opportunity in India but not enough as a standalone approach. That's why we have the second pillar: business models.

Business models are changing from ownership to car-sharing, which is why we are closely connected with the shared mobility space. Instead of inventing ourselves, we are connecting with startups. For example, we have invested in TruckEasy for freight aggregation for intra-city transport. It is still a small business but gives us valuable insights in the CV sector where we are market leaders. Such mobility concepts will also evolve into businesses from a revenue-sharing perspective.

The third pillar—partnerships—has enabled faster access to the new mobility space and disruptive technologies. For me, these three pillars are an answer for the opportunity we see in India: CESS (Connected, Electric, Shared, and Sustainable) Mobility.

Q. What have the business model learnings been?

In startups, we naturally find speed, simplicity and agility, the key ingredients I mentioned earlier. Startups are not complex, they are simple in structure and processes. It is the best way for Tata Motors to learn from ventures that have a different culture—how do they manage their innovation power on one side, with financing needs on the other? It isn't about putting our culture on them, but imbibing our observations of them back into Tata Motors.

Our play has never been about investing $100 million here and another $100 million there. Instead, we support third parties to leverage technology, enter new business models, and grow these opportunities with changes in demand and customer expectations. It unleashes a lot of potential while working with our partners and within Tata Motors. As a result, it has become a norm at Tata Motors to have ring-fenced and dedicated teams. We select people based on their passion for the task they are assigned to, while being flexible to our working structure.

Q. Are there concerns in electric mobility about how to monetise, and get returns on investment because scale will take time in India?

We need scale. But we need it as an ecosystem. That's where the Tata Group has a good starting point because of the One Tata theme. The group has companies like Tata Elxsi, Tata Power, Tata Motors, Tata Chemicals and AutoComp Systems, Tata Capital, and so on. This is important because, for instance, the Phase II of the FAME India Scheme—Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of (Hybrid and) Electric Vehicles in India—stipulates incentives based on an operating-expenditures model—not a CapEx model.

This means the central government will incentivise state transport units (STU) to buy more electric buses based on the OpEx model adopted by STUs. This provides scope for turnkey solutions: we invest, provide infrastructure for the depot, charging infrastructure to the largest extent possible. Our group has all these capabilities in-house. Even for the PMP (Phased Manufacturing Programme) localisation requirements, we have the willingness and competencies to invest in the ecosystem. This ecosystem approach is important.

We also need to leverage our current assets for customer-centric solutions in India. The Indian customer wants nothing less than the best solution, but it also needs to be affordable. So frugal engineering is key.

We surprised the world at the Geneva International Motor Show in 2019, by displaying the Tata Altroz, which showcased that we can do electrification in a dedicated electric style by leveraging the new architectures introduced—Alfa and Omega—which are ready for electric battery too. In 2018, it was just a statement. We are now about to launch the Altroz in the ICE [internal combustion engine] version. It will also be available with an electric battery underfloor, [battery] range that meets 90 percent of the use-case requirements in India, while providing an affordable solution.

This is possible because we use the architecture that we have already invested in. We use [production] capacity that already exists and suppliers who work with us on components for the ICE variants. So electrification is more of an alternative powertrain solution for us than a completely new invention. Yes, the powertrain is new, technology-wise. But the way we integrate it in the overall passenger-vehicle system leverages electric as a flexible play in line with the market demand. Because, honestly speaking, it's going to be fully integrated.

Do I care if the market adaptation is going to be as fast as 30 percent share of electric cars in 2023? Or 10 percent? At this point of time, we would rather lean on an estimate that is going to be at the higher end than the lower end. By being flexibly integrated, as long as I have the base capacity available with my supply chain—and we have made great progress—Tata Motors is effectively prepared to play as the market moves to electric technologies.

Q As technologies mature fast, you also have a near-term regulatory deadline in April 2020, the Bharat Stage-VI. What has that transition entailed?

It is the single-largest investment on a cumulative basis that Tata Motors has ever performed. The switch to Bharat-VI includes all our powertrain solutions and products. This wasn't just about meeting certification requirements, but also about applications.

From PVs to CVs, heavy trucks and buses, we have the largest range of vehicles. But we whole-heartedly supported the government proposal to move from BS-IV to BS-VI in record-time of just three years. The rest of the world has taken five or seven years to take the same technology steps. We appreciate that the need of the hour is to fight pollution and improve fuel-efficiency, and BS-VI is a step in that direction—of course, the BS-VI compliant fuel should also be available to maximise the impact.

Nevertheless, until then, BS-IV would be the technology frontrunner. In 2014, we developed Selective Catalytic Reduction (SCR) for our medium and heavy duty trucks that have BS-IV compliant engines. It uses less fuel since the engine is tuned to cut nitrogen oxides and can instead be set up for performance and economy. Also, it needs fewer active ‘regenerations’ of diesel particulate filters to burn off soot, which in turn uses less fuel.

This was a marginal and evolutionary step before everyone gets to BS-VI. But we have at least invested in BS-IV to cater to the customers who are familiar with the new technology and are prepared for the next step to BS-VI. Nevertheless, switching to the next emission standard before the hard stop of March 31, 2020 entailed that no BS-IV vehicles can be sold or registered anymore. This is a huge challenge, and even more critical in the current market environment. It's been extremely challenging to tackle subdued demand and slow-moving stock, keeping our capacity employed, while dealing with the ban on selling and registering of BS-IV compliant vehicles.

Q. What was the rationale behind Tata Motors launching so many car models in 2018?

The five passenger-car launches in less than two months ahead of the 2018 festive season brought some surprise to the market and some pride to us at Tata Motors. These launches created some attraction and got attention in the market, despite the subdued demand. It kept us in the market longer, which confirms that the Indian customer is quite keen for new products. Even in a subdued market, new vehicles can create an attraction in India. It was also proof of the agility of Tata Motors, as far as a flexible response to change in demand is concerned. We carefully listen to customers and translate their expectations to new products and variants. As each product has a certain point of time in the market, it comes to five models in two months. We delivered, and there was a great return on it.

Q. How has the hiring and talent management changed with more software content now in vehicles than ever before?

I would put it as talent and skills. The talent pool needs to change in an environment that moves more towards software—hardware to software, vehicles to solutions. With vehicles moving rapidly towards digitisation and experience, there has been a tremendous impact on the required skills.

This starts from the top. As a CEO, it's not good enough for me to be hardware-focused. I need to be tech-savvy, focused on the latest developments in the digital space—data, analytics, artificial intelligence. CEOs are obliged to give direction based on these subjects. The expectations of the executive committee members are the same. Our discussions are shifting more and more to these areas in a highly competitive environment, characterised by disruption.

The problem gets amplified at the lower levels for hardware-oriented companies with good electronic content. Now software stands front and centre. And while we are not a software company, we need to build these skills internally. We need to develop this talent because it's going to change the equipment profile and lead to a lot of training programmes internally for our talented engineers. We need to keep them updated.

At the same time, every opening into the organisation or fresh recruitment from universities and external recruitment for management positions needs to be in line with the new requirements. The management and executive management defines the need, and is focussed on taking the organisation to where we need to be. It's all about anticipation.

.jpg)

.jpg)