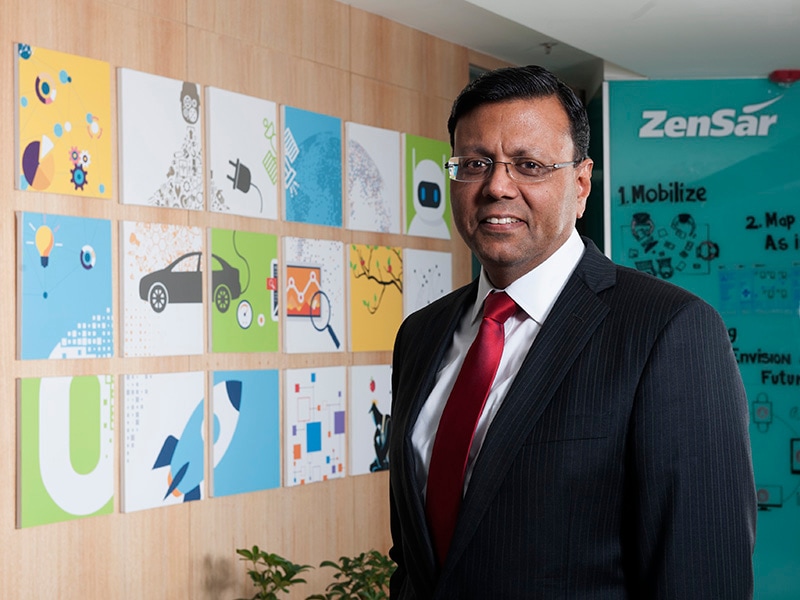

'The new wave of productivity will come out of data and new age technologies'

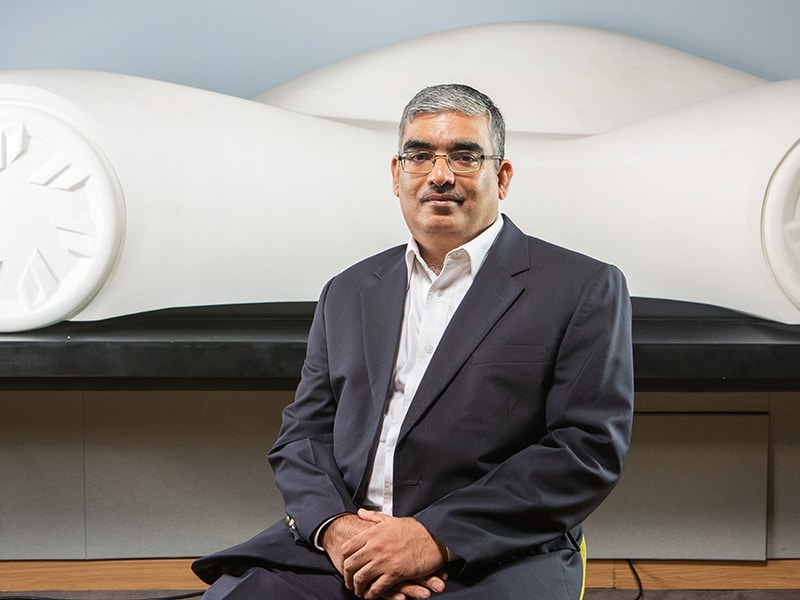

.jpg) Image: Aditi Tailang

Image: Aditi TailangForbes India in conversation with Rajesh Jejurikar, President of Mahindra & Mahindra's Farm Equipment Sector, on how the Rs 21,988-crore business unit is evolving from being a tractor manufacturer to a technology-driven company in the shared services economy.

1. Let's start with the Mahindra & Mahindra vision of Farming 3.0. What was the genesis of this?

As we think about food needs of the world and what's going to happen 20 or 30 years later, we realise that food production needs to go up globally by around 70%. Most of the arable land has already been cultivated, so there is a limited amount of arable land. Hence, productivity will drive food needs of people. And we believe we have a significant role to play in enabling productivity. And a lot of the new wave of productivity will come out of data, analytics and new age technologies around digitisation.

When we started thinking about Farming 3.0, we were building a strategy that is not about being here to just sell tractors. We are here to sell a solution, which takes our customers towards an outcome. This whole journey is of moving from being a company, which is a manufacturer—as you like to call us—to somebody who will help our customers achieve their outcome. It means defining the boundary of outcomes as improving yields and productivity. That's the journey we are on.

2. When did this journey begin and how has it evolved?

Farming 3.0 has multiple legs of how we will use technology. It comes from the vision of democratising technology for farmers with small land-holdings. There are many new technologies that are deployed in the 1,000-2,000 acre farms around the world. What can we draw out of those new technologies and make them affordable for and accessible to small landholding farmers?

So, that is the vision: getting these farmers technologies that help them get better produce without having to spend money beyond what they can afford.

3. How is digital adoption playing out in the interiors of India? Have 4G and affordable mobile handsets actually begun to impact M&M's business strategy?

Clearly, there is a very, very high internet usage now in rural India, estimated at around 25% which is pretty high. People say that in the next two or three years, there will be as many rural consumers of internet as urban. So, internet penetration has grown dramatically, especially in the past two or three years. Mobile players as well as improved and affordable bandwidth have made that possible: to create a new segment.

The question is: what are the primary uses today for rural internet customers? The first is entertainment, second—believe it or not—is Facebook and third is WhatsApp. So, these are three things that today rural consumers are using the internet in humongous quantity.

Let me give you an example from two or three years ago: consumers who wanted to exchange tractors and needed to quote a price. So, the dealer salesman would take photographs and then WhatsApp the photographs, to the dealer salesman on the other side. He could get an agreed-upon exchange price. This helped them discover price right then just using photos on WhatsApp. So, a lot of video content. Facebook is the other social media, which has pushed us to work on social initiatives like 'Prerna' to empower women farmers. For this, we have used a lot of Facebook and YouTube videos to create awareness around women's empowerment.

Clearly, the internet wave right now is around entertainment and communication. Has it reached a stage where the rural base is going to do e-commerce? Not yet. There is a journey to traverse, but we believe the building blocks are in place.

4. For a manufacturing company, how does technology play out in terms of Mahindra & Mahindra's factories getting smarter?

You must come to our Zaheerabad facility in Telangana, where you will experience a factory that is smart and technology-enabled. It is actually now a paperless plant, using so much of technology there. We have created our own system using sensors and IoT (Internet of Things) that create alerts. We believe that it will reduce breakdown time by 30-40% with dramatic reduction in repair and maintenance costs because we have built in the alerts.

Predictive analytics tells us in advance what could break down. We proactively fix that, so we don't have breakdown time and cut back on repair costs. We know what to maintain at what stage, depending on how it is being used or worn out. There is tremendous value that we are seeing digitisation play in the way manufacturing is done. We are going to seamlessly connect this to front-end, supply chain, so on and so forth.

5. How have you had to reimagine talent and hiring to become a technology-driven manufacturer, considering the mass-manufacturing mantra a decade ago?

We are hiring a very different kind of talent. That still constitutes a small proportion of our workforce. So, it is not like the workforce is completely changing. But what we realise is that these are specific skillsets. We have to curate or incubate them differently in an organisation. In the latter, people are more digitally savvy and are able to make the connection with agriculture. That's one way in which we have brought in talent.

The other way is to work with start-ups, for which we have done some interesting tie-ups. One of our investments is in a company in Canada called Resson Aerospace. It is into predictive analytics for precision agriculture. We are doing pilots with them here, but Resson is also doing a lot of work with leading players in potato and other crops in the US and Canada. That is also a source of talent for us because, maybe, we can't hire that kind of talent or that kind of talent may not want to work with us. But leveraging the global and local talent ecosystem is how one will have to create access to talent that can deliver these kinds of technologies. So, we shouldn't always have the mindset that this talent is going to rest in our company and our premises.

We have invested in a start-up that began at IIT (Indian Institute of Technology) Bombay called Carnot Technologies. They now have 20-30 people. Then, we have started an Ag Tech Center at Virginia Tech Corporate Research Center in the US, again towards advanced technologies in this area. We created a talent pool there. We have had to find different ways to prepare the organisation to deliver different kinds of outcomes.

6. Tell me about DigiSense, which I understand is a group-wide digital initiative. How has the farm equipment sector benefited from it?

We have DigiSense right now on some of our small tractor platform models like JIVO and YUVO. DigiSense is basically an IoT-driven platform device. It helps the farmers get more information about the tractors. Take a technology like geofencing. If I am a tractor-owner with a fleet of 10 tractors, I want to know where my tractor is. Geofencing helps me know if a tractor is moving out of a pre-defined area and how they are being used. This is also useful in our applications like Trringo, where we enable leasing of tractors. It also helps with alerts related to maintenance, usage of implements, and various technologies relevant to the farmers. All of these have come out of DigiSense.

7. How have the strategic acquisitions or alliances in Turkey, Finland and Japan evolved?

Each of these have been done with a purpose. One of the objectives is to create market access for Mahindra & Mahindra brands. The other is to create technology centres. As we have been moving away or moving on from tractors to farm machines, we needed the technology capability to do that.

It would have taken forever if we had to create that technology capability in-house. In a way, we are a late entrant. So we started looking for people and places to build this capability. We have created three global centres of excellence. In Japan, we are looking for the rice or paddy value chain, which require lightweight tractors, rice transplanters and rice harvesters. This product portfolio is developed only out of Japan.

In Finland, we are doing all other harvesters. All our harvester product development is being done from Sampo Rosenlew in Finland. Similarly in Turkey, we are building capability and competence for farm machines development with a company called Hisarlar—products like soil tillage, silage balers and so on. An acquisition like Erkunt Traktor (in Turkey) has been for market access. It is a number three or four brand in a large tractor market. But the first three are for us to leapfrog the technology curve.

8. As technology lifecycles have shrunk, how has your lexicon itself changed from a decade ago?

In the conventional tractor market, customers like continuity. They are looking for assurance rather than disruption. They want confidence that what they use is not going to create problems. Contrast this with our automotive consumer, where we continuously need to introduce features. That is not the case with the tractor consumer. This consumer wants continuity and assurance. Change to new is slow and cautious.

But we believe there's an opportunity through digitisation to create innovation and disruption. So if you look at precision farming, these kind of technologies will create value that connects back to the original question around Farming 3.0. It is around thinking of this business beyond selling machines to 'farming as a service'.

To think about what farming-as-a-service means it is about what we can do to add value? That's why we have the Samriddhi centres. Its role is to become an advisory to the farmer, help them make the change and evolve with technologies to newer practices like precision farming. We also have an advisory app called MyAgriGuru. All these digital initiatives are part of our journey to engage with farmers before their purchase, after or irrespective of whether they have made a purchase.

9. But would you agree M&M Farm Equipment Sector has had a far more patient approach to investing in execution and brand-building on the digital side? Do you need to be more aggressive, compared to start-ups?

In farming, you have to be patient for two or three reasons. One, anything new that you do has to be validated from season to season. We don't have a 12-month validation cycle. There may be a season that lasts eight weeks, so a farmer may do some work in potato cultivation in those eight weeks and then wait for the next season. So, one has to be patient.

Most agri-tech companies don't have a hockey-stick ramp-up because they have to prove their product. It is going to be different in different soil conditions, climate, and they have to adapt. It is not like one product is going to be globally acceptable.

Second, our consumer buying behaviour itself is cautious. So both—the need to prove our technologies and consumers' ability to adapt to the new—are effort intensive. And that's why we think we have a competitive advantage. As a stable and established player in farming, we are here to stay. It's not for somebody who wants to make a quick buck and run.

Take the example of Trringo. There are elements of the business model, which need fine-tuning. We had started off with a franchise-hub business model. Now, we have noticed the franchises may not make the kind of financial returns that is needed. So while I have a customer value proposition, what do I do about the intermediary business proposition? And then though we may start thinking of an initiative that I am going to run it on the outside the main organisation, we also feel we are not leveraging our core assets, which is my dealer network and current customers.

So we are exploring pilots now to bring it more into the mainstream than running it independently. Any business model has to go through an evolution of trial and learn.

Today, the CEO engagement is around seeing how viable my customer proposition is, and then what technologies allow me to do that, and how confident I am of those technologies. We have tech teams and digital teams who then interconnect various digital initiatives like, say, Trringo and DigiSense.

.jpg)