Inside Naspers' big bet on India

How a single $32 million wager transformed Naspers from a traditional newspaper business in South Africa, and how the India portfolio ties in with its global tech investments

“We look for investments that can have the greatest societal impact.” Bob van Dijk, chief executive, Naspers

“We look for investments that can have the greatest societal impact.” Bob van Dijk, chief executive, NaspersOn a sunny September morning in Amsterdam, Naspers’s executives huddled together on the trading floor of the Euronext exchange. Seconds later, they broke into a rapturous chant: “Ten, nine, eight, seven…” On the count of one, Bob van Dijk, chief executive of the South African media and internet conglomerate, struck the opening gong. A burst of applause followed.

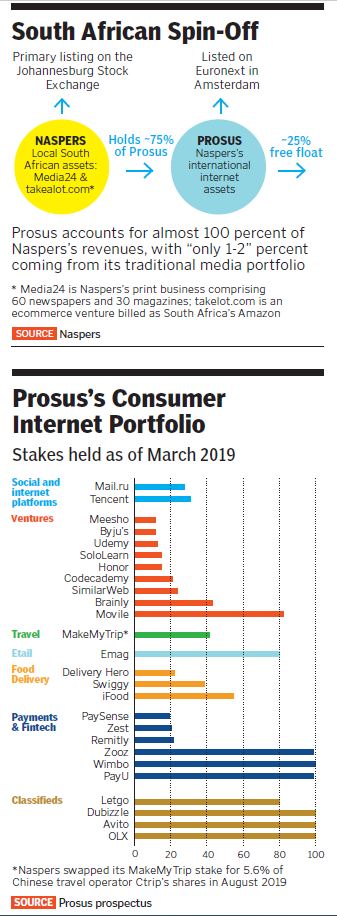

Prosus, a spin-off of Naspers’s global empire of internet assets, including a prized 31 percent stake in Chinese gaming and WeChat giant Tencent, marked its debut. And stock market investors were charmed. They traded the stock at €76, well above its reference price of €58. Prosus’s value soared to €125 billion or $138 billion on the day, making it the largest company to trade on the Euronext after Royal Dutch Shell (€209 billion) and Unilever (€200 billion). At the time of going to press, its stock price was €67.

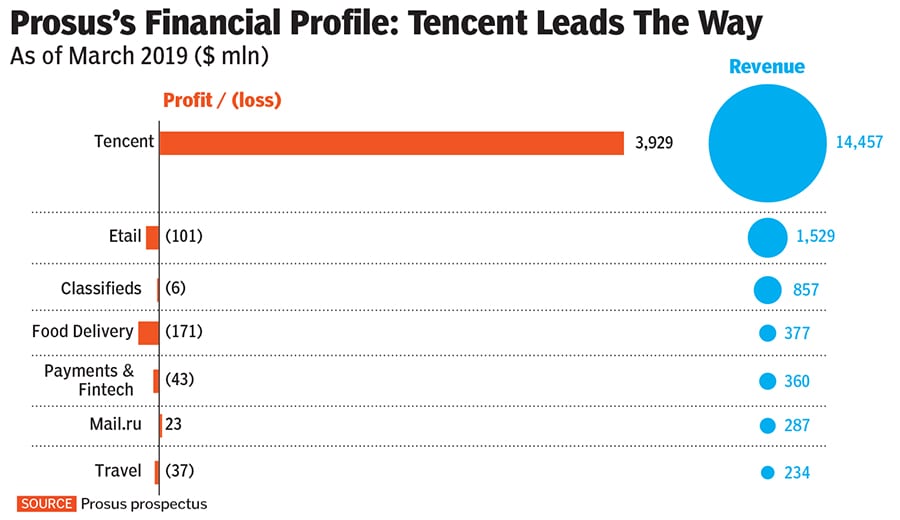

But that’s not the only reason. In March, when Naspers announced its decision to spin off its internet assets into a separate holding vehicle, its market cap was just shy of $100 billion on the Johannesburg bourse. But the value of its Tencent stake alone was $133 billion. The yawning gap meant investors ascribed zero value to Naspers’s other interests, including its 20 classifieds businesses that serve 340 million people every month across five continents, its operationally profitable global payments arm PayU, and its food delivery bets that span 40 countries.

Moreover, the rise in Tencent’s value over time made Naspers too big for the Johannesburg stock exchange (JSE): It had risen to 25 percent of a share-weighted index of the top 40 companies, up from 5 percent in 2013. Local investors were forced to sell Naspers’s shares to keep their portfolios diversified, further deepening the share price discount.

While the Amsterdam listing should narrow it, the move is yet another corporate reinvention for Naspers, which began life as a newspaper publisher in Stellenbosch, the wine capital of South Africa, in 1915. De Nasionale Pers Beperkt or the National Press Limited, as it was known then, served as a Dutch-language mouthpiece for the apartheid regime in the country. Quietly, this unknown print publisher transformed itself into one of the world’s savviest technology investors.

*****

To understand Naspers, you have to understand how it went about reinventing its business to keep up with the changing times,” says Ken Rumph, equity research analyst at London-based investment bank Jefferies.

When Koos Bekker—the man responsible for Naspers’s $32 million bet on Tencent in 2001—joined the company in 1985, it was still a traditional newspaper business. Quick to see that the onslaught of television would eat into print advertising, Bekker led Naspers’s foray into pay-TV.

Bekker went on to use the earnings from print and pay-TV to bet on the brewing internet. He invested in a slew of South African digital news sites, while simultaneously scouting for opportunities in China “because over the past 3,000 years, most of the time China was the world’s biggest economy”, says Bekker in the book Non-Bullshit Innovation by tech journalist David Rowan.

But Naspers bungled its early bets in China, including investments in a Beijing-based internet service provider, a financial portal in Shanghai and a sports portal that was at one time the biggest in China. “They were all write-offs—we lost all our money,” Bekker tells Rowan. The mistake, he says, was that Naspers brought in Western executives to run the companies without giving local business culture and knowledge their due. “So we thought, why don’t we do the complete opposite? Let’s go find the most able Chinese management team and instead of telling them what to do, what about shutting up and letting them run the show? That’s when we invested in Tencent,” recalls Bekker in the book.

Tencent was then a loss-making startup but its instant-messaging system QQ had almost 2 million users. Bekker saw a spark in the co-founders and acquired almost half the company for $32 million. As Tencent’s value soared, Naspers’s fortunes soared; “You never lose with Koos” became a popular saying in South African investment circles.

Today Naspers’s 31 percent stake in the Chinese internet and gaming giant is worth a whopping $133 billion. “It is not just Naspers’s best investment to date,” says van Dijk who succeeded Bekker—now the chairman—as CEO in 2014. “It is the best venture investment of all time,” he says. The only other punt that comes close is SoftBank’s $20 million gamble on Chinese ecommerce group Alibaba in 2000. That stake, now worth $132 billion, has turned SoftBank—just like Tencent transformed Naspers—into one of the world’s most powerful investors.

*****

Tencent’s extraordinary rise has allowed Naspers to bet on promising internet businesses around the world. “We look for investments that can have the greatest societal impact,” says van Dijk. Naspers’s classifieds arm is a case in point. People buy more things than they need, and given the planet’s limited resources, they will eventually have to buy and sell used goods, believes van Dijk. With brands like OLX that operates primarily in India and Brazil, Letgo in the US and Avito in Russia, Naspers serves millions of customers every month, making it the world leader in classifieds.

Societal impact may not be what usually concerns venture capitalists (VC), but then again, Naspers isn’t a traditional VC. It doesn’t operate a fund, lacks external limited partners and has no exit horizon. This means that Naspers has no limit on how much to invest in a company and the monies it provides are “long-term” and “patient” in nature, explains Ashutosh Sharma, who leads the activities of Naspers Ventures in India, the arm that invests in fledgling ventures that have the potential to become global businesses.

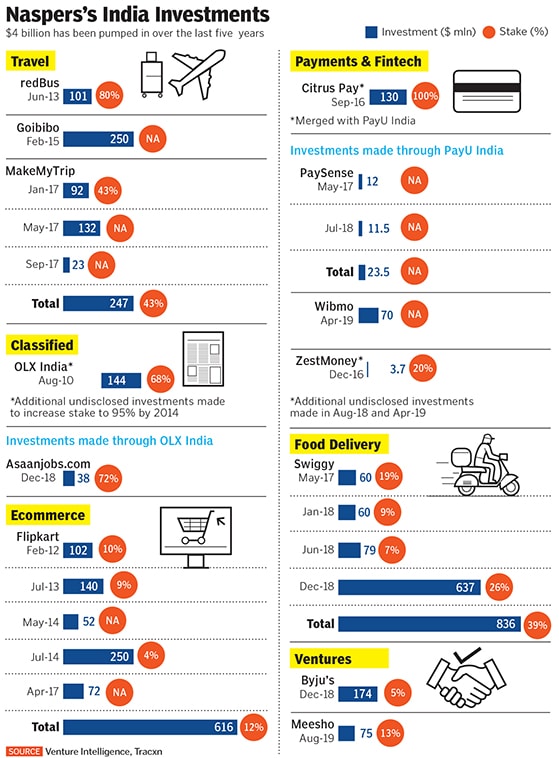

The long-term nature of Naspers’s commitments is most evident in India, where it has pumped in $4 billion over the last five years. “We started investing in India really early on, ahead of the curve,” says van Dijk. Back then, in 2007, mobile internet connections were limited and terribly slow, but the young population and quality of entrepreneurs excited Naspers, he says. In the case of ibibo, Naspers’s first investment in India, the startup pivoted several times before it worked out.

Ashish Kashyap set up ibibo as an incubator that would enable him to invest in and build multiple startups in early 2007. With $5 million as initial capital from Naspers, ibibo experimented with gaming, social media, search and advertising. By 2008, Kashyap established travel portal Goibibo and payments platform ibibo Pay (now PayU) to enable people to pay online for its services. Around the same time, Tencent, already part-owned by Naspers, started backing ibibo too.

Along the way, Naspers launched ecommerce entity Tradus—a British brand it had acquired in 2007—under the ibibo umbrella, but it quietly folded up operations soon after.

Meanwhile Kashyap completely transformed his venture into a travel and payments business by 2011, competing with MakeMyTrip (MMT) and Cleartrip in the former category, and CCAvenue and BillDesk in the latter. “Naspers backed my decision and conviction to solve the travel and transaction problems we had, even though this did not resemble its playbook in any part of the world at the time,” recalls Kashyap.

“Naspers simultaneously wears the hats of investor and operator.” Jitendra Gupta, founder, Citrus Pay

“Naspers simultaneously wears the hats of investor and operator.” Jitendra Gupta, founder, Citrus PayLater, when Kashyap decided to buyout bus ticketing platform redBus for $101 million in 2013, Naspers backed him with the capital. Despite the initial integration challenges, Kashyap was able to “re-engineer” the platform and establish it in international markets like Southeast Asia and Latin America. Meanwhile, Goibibo entered the hotel booking business and quickly started scaling. So much so that by 2014, says Kashyap, ibibo had grown to become the “number one in hotels, number one in bus ticketing and number two in air travel”.

“You can see from its early investments in ibibo, and the redBus acquisition, that Naspers was looking to create market-leading companies,” says Padmaja Ruparel, president of the Indian Angel Network. Sure enough, when ibibo merged with MMT in January 2017, Naspers invested an additional $92 million in exchange for a 43 percent stake in MMT, building the largest online travel agent in India. Shortly after, Kashyap exited and set up fintech venture INDwealth. Naspers pumped another $132 million and $23 million in MMT in May and September 2017, respectively.

“Naspers is a visionary global investor. we’re a better organisation at scale since it has come on board.” Sriharsha Majety, co-founder and CEO, Swiggy

“Naspers is a visionary global investor. we’re a better organisation at scale since it has come on board.” Sriharsha Majety, co-founder and CEO, Swiggy“One learning from our early foray into India is to focus on the entrepreneur… it’s also given us a high appetite for risk,” says van Dijk. He adds that Naspers tends to “double down” on investments in promising ventures. Those that can swiftly scale by drawing on network effects are favoured. As are those that adopt a mobile-first strategy because the “high-growth” markets that Naspers primarily operates in, including China, India, Russia, Central and Eastern Europe, Latin America, Southeast Asia and Africa, largely eschewed desktop computing for mobile internet.

“Naspers is an early pioneer in the food delivery space. We believe it’s still day zero in the food tech space.” Ashutosh Sharma, India Head, Investments and M&A, Naspers Ventures

“Naspers is an early pioneer in the food delivery space. We believe it’s still day zero in the food tech space.” Ashutosh Sharma, India Head, Investments and M&A, Naspers Ventures

Image: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes

True to Naspers’s style of placing an “overweight on entrepreneurs” as Sharma of Naspers Ventures in India puts it, Gupta was appointed managing director of PayU India, while his co-founder Ambrish Rau was made CEO. “The operations were run locally by us,” says Gupta. “Where Naspers added value was in drawing on its experience of running businesses across the world and sharing best practices with us. That’s why they are not just investors, but also operators.”

PayU India went from being a loss-making entity at the time of the merger to turning a profit last year on revenue of $127 million (`882 crore). In fact, India is the first country to turn profitable for PayU which operates platforms with over 300 payment options in 18 markets worldwide. The successful merger, the rapid scaling up—India accounts for more than half of the 900 million transactions processed by PayU in FY19—and the combined entity’s market leadership are responsible for the reversal, says Anirban Mukherjee, PayU India’s recently appointed CEO. Rau has taken on a larger role at PayU while Gupta exited earlier this year to pursue another entrepreneurial venture.

The setting up of LazyPay, a product of PayU India that provides online shoppers with quick and easy access to micro loans at checkout, has seen “tremendous traction” and was also key to the turnaround, says Gupta, the force behind it. PayU India has since made minority investments in PaySense and ZestPay, startups that provide digital credit using alternative data, as part of a larger strategic foray into consumer lending. Says Mukherjee, “Our ultimate aim is to be a full stack financial services provider.”

*****

Days after Naspers invested $174 million in a $540 million funding round in Indian educational technology startup Byju’s in December 2018, it led a $1 billion series H round in food delivery service Swiggy, where it contributed $637 million. Both sectors, ed-tech and food tech, exemplify Naspers’s twin concerns of addressing major societal needs using technology. And both investments were made alongside Tencent. In the case of Byju’s, the Chinese conglomerate was the first to pump in money in an earlier round, while Swiggy’s latest round saw Tencent follow Naspers’s lead. “We discuss opportunities with our friends at Tencent,” concedes van Dijk.

The difference is that the investment in Byju’s was Naspers’s first brush with the startup. Whereas the Swiggy round saw Naspers “double down” on the food delivery platform, which claims to be India’s largest with 1,45,000 restaurant partners in 500-plus cities, for the fourth time. Its shareholding in the startup is now almost 40 percent.

“Naspers is an early pioneer in the food delivery space,” says Sharma, referring to the group’s investments in iFood in Brazil and Delivery Hero in Germany, which, together with Swiggy, operate in 40 countries and reach 4 billion people. He adds, “We believe it’s still day zero in the food tech space.” In India, for example, the average household orders one meal per year versus 13 in the US and 10 in the UK, indicating potential headroom for growth. Increased mobile penetration, population migration to urban centres and changing consumer lifestyles with a preference for convenience are upsides.

Even so, why the push on a company like Swiggy that’s yet to turn a profit? “We have a strong plan toward achieving profitability,” says Sharma, “but it’s not something we can discuss.” That said, when Naspers first met Swiggy in 2016, the startup’s core markets were unit economic profitable, despite the first-party delivery model it had in place unlike iFood and Delivery Hero that ran on third-party logistics. “The founders’ vision, audacity, hustle and ability to execute set them apart,” says Sharma.

“Naspers is a visionary global investor. It’s the right partner for us from a long-term perspective… we’re a better organisation at scale since it has come on board,” says Swiggy’s co-founder and CEO Sriharsha Majety. Transaction volumes have grown 10x since the first round of funding by Naspers in June 2017, he says.

Naspers’s 2019 annual report shows how effective its strategies have been. The company’s internet investments, housed under Prosus, brought in revenues of $19 billion and a trading profit of $3.3 billion, up from $16.4 billion and $3 billion in FY18. (Virtually all revenues are generated from online activities with Naspers’s traditional media portfolio accounting for only 1-2 percent of revenues.) Its classifieds business turned a profit in aggregate for the first time, its payments arm—led by the India business—became operationally profitable in aggregate, and Naspers sold its stake in ecommerce business Flipkart to Walmart for $2.2 billion at an internal rate of return (IRR) of 29 percent. “We’re still bullish about Flipkart,” says van Dijk. “But we like to be strategic long-term partners. With Walmart coming in we knew that wouldn’t be the case, so we exited.”

In another key move, Naspers swapped its 43 percent stake in MMT for a 5.6 percent share of Ctrip, earlier this year. The transaction saw the Chinese travel operator become the biggest shareholder in MMT with a 49 percent stake, while Naspers netted an IRR of 24 percent. “Naspers has been a great partner,” says MMT’s founder Deep Kalra. “But we both felt the synergies with Ctrip would be greater... Naspers still remains invested through Ctrip.”

Adds Rumph of Jefferies, “You can see [from the transaction] that Naspers’s strategy is to be the last man standing.”

*****

The Prosus listing hasn’t been the only attempt by Naspers to fix its share price discount. In 2018, Naspers trimmed its Tencent stake for the first time, from 33 percent to 31 percent, pocketing a cool $9.6 billion. And this year, it spun off MultiChoice, the pay-TV business Bekker set up in 1985, as a separate entity on the Johannesburg bourse. The discount in Naspers’s share price subsequently narrowed from about 50 percent to 35 percent.

While Naspers hopes the Amsterdam listing will further reduce the discount, Rumph argues that it will do so only partially. “The share price discount is also partly due to Naspers’s conglomerate structure and governance issues which the listing cannot mitigate,” he says. Naspers has a voting structure that gives super voting rights to a small group of insiders. This prevents activist shareholders from challenging the management if things go wrong.

“It’s a pity because if it wasn’t so, its other investments, which are overshadowed by Tencent, would get their due,” says Rumph. Even so, Naspers’s executives are busy finding the next frontier. “Machine learning is the next big thing,” predicts van Dijk. So can Naspers replicate its Tencent bet or was it a once-in-a-lifetime find? Laughter crackles over the telephone line. Says van Dijk, “Everyone is looking for the next Tencent.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)