No-holds-barred Anurag Kashyap: AK47, Reloaded

As Anurag Kashyap turns 47 next month, he will still provoke—as a filmmaker and writer, but no longer on Twitter

Image: Mexy Xavier

Image: Mexy Xavier

Moviemaking is like an expensive form of therapy. Only you don’t have to pay for it. Other people pay for it.

-Filmmaker Tim Burton

For Anurag Kashyap, the therapy continues more than 15 years after he made his first movie that never got released in India, Paanch. The film ran into problems with the censor board, which couldn’t figure why the filmmaker insisted on making dark cinema that glorified violence and drugs instead of ‘wholesome and healthy entertainment’. The film, inspired by the gruesome murders of the Joshi and Abhyankar families in Pune in the 70s, was eventually screened at festivals in Hamburg and Los Angeles, among other cities.

Two decades later, Kashyap—along with a rash of filmmakers, writers and producers, and an eager audience—has embraced a new platform that has so far eluded the scissors of the censors: Over-the-top (OTT) video streaming. And in an impish blast from the past, Kashyap has brought back one of the provocative bits from the Paanch era into the second season of the Sacred Games original web series that premiered on August 15: A masturbation scene. Kashyap didn’t reveal more when Forbes India met him in end-July, but did let on: “There are things (in Sacred Games 2) that are going to provoke.”

On the cusp of his 47th birthday on September 10, Kashyap will continue to provoke—but not on Twitter any longer, where till recently he would forcefully put forth his views (threats to his family and his daughter compelled him to quit the microblogging platform). Now it will be his films and scripts that will do most of the talking. And there is a difference from the past; now he won’t tilt at every windmill along the way, the way he did when films like No Smoking (2007) and Bombay Velvet (2015) bombed. “I will still say what I want to say. But now I am more conscious of how to say it,” he grins, as he offers to show Forbes India a rough cut of a movie that he is making for his new production house, Good Bad Films. “I am not going to shy away from making a political film,” he says, disclosing the nature of his yet-to-be-released ‘political’ thriller. “I won’t talk about it,” he smiles, as he rolls another cigarette.

Moviemaking may be good therapy, but Kashyap also had to go through rehab of the real kind as he dealt with a year of depression. His production company Phantom Films shut down in 2018 after partner Vikas Bahl faced sexual harassment charges. “I struggled to figure out where I went wrong and I found what I did wrong... I don’t know how to run a company. I don’t understand finance or the legal stuff. Those were inconvenient things for me. I would rather be sitting and writing and creating than tackling those things. I would leave such stuff to other people. Now I have a professional setup where the ideating space is different from the production space.”

Good Bad Films, avers co-founder Dhruv Jagasia, will focus on cinema that “needs to be made or liked to be watched”. Akshay Thakkar, the other co-founder, points out that good cinema can be consumed in a multitude of ways and mediums. “We want to explore all of them.”

Akshay Thakkar (left) and Dhruv Jagasia, co-founders, Good Bad Films

Akshay Thakkar (left) and Dhruv Jagasia, co-founders, Good Bad FilmsImage: Mexy Xavier

Kashyap knows his audience: Not those who will line up in a queue on Fridays. “My movies don’t have immediate gratification or returns on box office.” His audience are those busy with work and who will watch his films at their own time and convenience. That’s where streaming platforms come into the picture. “He (Kashyap) is a transformed man now, more fearless as a person and a filmmaker,” adds Jagasia.

Kashyap is clear on the way ahead: As filmmaker/writer, as a producer, and as an actor (not just in films, but also in ads), each with its own motivations. As a director, he will do exactly what he wants to do—not what anybody wants him to do, including his audience. So, for instance, if there is a chorus to do another gangster saga like the wildly successful Gangs of Wasseypur (GoW, 2012), he is unambiguous when he declares that he wants to “run away from the formula. I am going in the opposite direction. I want to do something new”.

As a producer, Kashyap is more accommodating. “My first lesson as a director is I don’t want anyone to tell me what to do. So when I become producer, I will not impose how I look at things on others.” So, for instance, although Kashyap isn’t a big fan of biopics that glorify sportspersons, even if the soon-to-be-released Saand ki Aankh (on celebrated ‘shooter dadis’ Chandro Tomar and Prakashi Tomar) inevitably goes in that direction, he won’t protest. Yet even as a producer, he is not the typical one. “I am a creative producer. I will take responsibility of script, editing, post-production and casting. But I don’t take responsibility of finance, which I don’t understand.”

A similar rule applies when he is acting. “Would I make the film that I have acted in? No. But, when I act, I don’t question the director. I just follow orders.” He’s been doing just that down South in Tamil movies where filmmakers love to cast him in dark roles, like the one in the 2018 thriller Imaikkaa Nodigal. “I will do whatever they ask me to do,” he says with a guffaw. “Maybe they perceive me as a villain… I have big eyes, this smile… everybody offers me the same kind of role. I am a typecast. I fit into the mould of what they see me as. I am okay with that. But I don’t like to act.”

Clockwise from top: Gangs of Wasseypur, Raman Raghav 2.0, Gulaal and Last Train To Mahakali

Clockwise from top: Gangs of Wasseypur, Raman Raghav 2.0, Gulaal and Last Train To Mahakali

So why does he do it? “Because there’s unreasonable amount of money,” he chuckles. “I don’t see anything wrong in it. What I mean to say is if there is something I love doing, I would do it for free.”

The same thinking applies to the TV commercials, the latest one for Cadbury Perk. “For me it’s like one day of job and money. I do this only when I have free time and there is obscene amount of money.”

When he’s writing or filming or editing, it’s a different story. “I love being on the set… writing, making and editing movies. I shoot in the morning and edit at night. I still use a pen to write. I want to tell darker stories because most of the time I want to make people a little uncomfortable and laugh out of discomfort.”

Filmmaker Imtiaz Ali credits Kashyap for bringing a new kind of cinema to India. “He has a distinct type of film where people are allowed to be angry, imperfect, violent, dangerous and silly at the same time.” Cinema is a personal expression for him, adds Ali. “He always portrays everything personally.”

The discomfort that Kashyap talks about often results in film and fact coming together. Take, for instance, Mukkabaaz, a 2017 sports drama that dealt with caste and cow vigilantism. “For me, cinema has to be a chronicler of times,” he says. “I want to talk about things that nobody is talking about.”

Baradwaj Rangan, film critic and editor of Film Companion South, reckons that Kashyap’s films have a unique voice. They gravitate towards something that is exciting, different and have all shades. Spotted and recognised for his script and dialogue in Ram Gopal Varma’s Satya (1998), Kashyap went on to master the genre of dark movies. “While Varma couldn’t sustain and burnt out, Kashyap has,” he says. The challenge, though, for Kashyap would be to keep reinventing himself.

Kashyap doesn’t see a problem on that front. “There is more content in India than anywhere else. I never run out of content. I have content for the next six years.” The problem, he feels, is the lack of backers of that content. “They want to be safe. They want to tell stories the same way.”

Kashyap swears by one of GoW’s memorable dialogues that loosely translates (for a family audience) to ‘As long as India has cinema, people will keep becoming fools’. He feels today OTT is going the same way—of mass production resulting in a lack of quality control. “OTT is an opportunity a lot of filmmakers are wasting,” rues Kashyap. “(But) good content will survive.”

The obsession with good content also led Kashyap to launch his own streaming platform with friends, called myNK. Designed to bring foreign language films and documentaries to India, it is blockchain-based to prevent piracy. myNK will attempt to source rare movies by winning the trust of filmmakers, in the process eliminating the middleman. “The filmmakers upload the film, set the price and people watch it,” says Kashyap, who claims myNK has some 350 films. The idea was Kashyap’s, the investment came from a classmate who is now in Singapore, and the blockchain solution from another classmate.

It’s difficult to put a label on Kashyap, and perhaps even he would struggle to do that. His Twitter profile (which doesn’t exist today) may have been the best effort: ‘Neither Left nor Right or Centre. I am diagonal’. He’s also a risk-taker, bordering on the self-destructive. “I try to do something suicidal after success,” he says. The idea, he underlines, is to make one big film, one suicidal film, and a big film again. This explains why after the success of Dev D (2009) he came up with the box office dud, That Girl in Yellow Boots (2011). It’s that penchant to run as far away from the formula that worked.

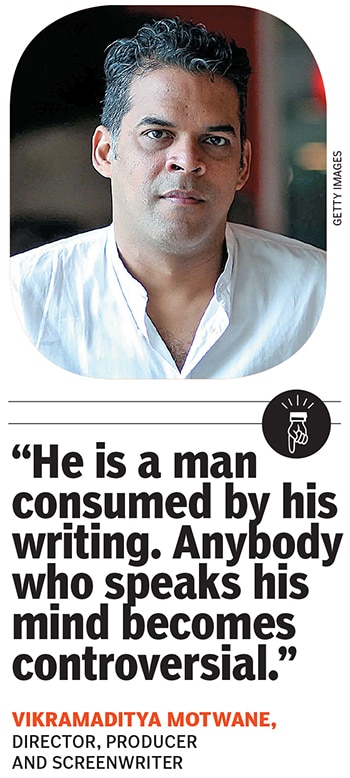

“He is a man consumed by his writings,” says Vikramaditya Motwane, who made his directorial debut for Anurag Kashyap Films in 2010 with Udaan and has known Kashyap for over 20 years. Kashyap, he reckons, is the best dialogue writer in India, adding that the man has made his share of mistakes and has now found his zone.

The maverick concurs. “I am in a good phase now, in a much happier space. I am enjoying my work so much more, and I am more fearless.” And he’s also more responsible. “All the consequences are mine.”

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)