The contagion in India's banking sector

The Yes Bank turmoil came with a one-off solution, but newer banks will not be spared from the infectious effect. And Covid-19 will only hurt retail lending more

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur

As soon as the moratorium for Yes Bank was lifted on March 18, entrepreneur Jasjeet Kaur went online and withdrew most of her money from her proprietorship account.

“If I keep the money any longer and some other crisis breaks out, I would be the biggest fool,” says Kaur, whose company sources lighting equipment for hotels, private companies and banquet halls.

She also had a housing loan linked with Yes Bank whose EMI was being paid by ECS (electronic clearing service), which she has now switched to ICICI Bank. “I was never happy with the customer service of Yes Bank… it had new relationship managers [RMs] every two months. The moratorium was announced on March 5 when we usually plan for salary expenses and other business outflows. When I called up my RM, he said he was not aware of any such development at the bank,” says Kaur, who had been banking with the troubled private sector bank since 2017 as it was close to her residence.

Kaur’s experience is not an aberration. Yes Bank has seen a sharp 39 percent erosion in deposits in nearly 12 months—from ₹227,601 crore in March 2019 to ₹137,506 crore as of March 5, 2020. The bank also saw a considerable deterioration in asset quality and had to increase provisioning for bad loans. And alarmingly, its common equity Tier1 (CET1), a key matrix, was at 0.6 percent against a minimum regulatory requirement of 7.37 percent.

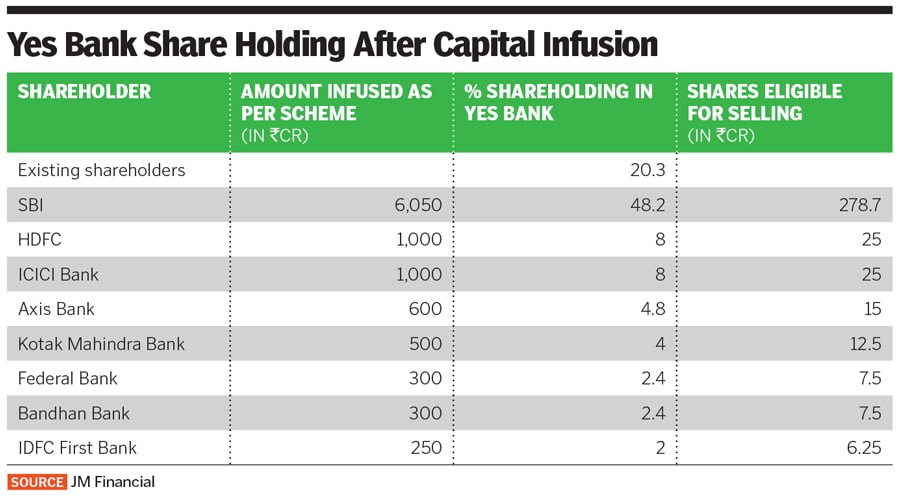

All these called for extreme measures. For the first time in India, the government and the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) got together to devise a reconstruction plan for the bank. India’s largest public lender, State Bank of India, housing finance firm HDFC and six private banks—ICICI Bank, Axis Bank, Kotak Mahindra Bank, Bandhan Bank, Federal Bank and IDFC First Bank—have infused a combined ₹10,000 crore capital into Yes Bank (see: Yes Bank Share Holding After Capital Infusion).

The Yes Bank stock, in March alone, nearly doubled to ₹60.8 (as on March 18) at the BSE. Yet, this does not promise a stable future. While the bank will be in a position to raise bulk deposits (considering that corporates are still depositing funds with the entity), the true test will be its ability to raise low-cost deposits, under its new managing director and CEO Prashant Kumar.

Failed institution

Rating agencies are adopting a wait-and-watch approach with regard to how Yes Bank tries to resurrect itself. “[Credit rating agency] Fitch would view Yes Bank as a failed institution, in terms of its intrinsic viability. The fact that there was extraordinary support from seven banks through a public-private partnership to keep it going implies that it had failed on its own,” says Saswata Guha, director and team head, Fitch Ratings in India. The agency does not rate Yes Bank but monitors its developments.

Yuvraj Choudhary, an analyst at Anand Rathi Securities, says the bank “will need to ensure that the quantum of erosion gets arrested quickly”. Banks run on confidence and lending is a trust business and Yes Bank appears to have lost that confidence from the investor community over the past two years .

“Depositors will take a call [on the bank’s future],” says Hemindra Hazari, an independent banking analyst who publishes his writings on Singapore-based research platform Smartkarma. Apart from UBS analyst Vishal Goyal in 2015, Hazari had warned in 2017 that all was not well with Yes Bank. This was after the bank, in 2016 and 2017, reported divergences in its gross non-performing assets (NPAs), which led to falsely inflating its profitability. The bank’s board did not take action against founder-promoter Rana Kapoor, the bank’s auditors or the senior management.

“If there is a learning from the Yes Bank episode, it is that promoters should not be CEOs. There should be a separation between ownership and management. The RBI must impose these practices strictly and apply them to all,” says Hazari, referring to a legal battle that the RBI had with Kotak Mahindra Bank, which favoured its founder and managing director Uday Kotak. The RBI wanted him to reduce his stake in the bank from 29.9 percent to 15 percent by March 2020 as per bank licencing guidelines. After the agreement, Kotak will have to lower his stake by only 4 percent by June.

In the case of Yes Bank, the problems emerged publicly after the RBI denied an extension to Kapoor beyond January 31, 2019. The central bank highlighted “serious lapses” in corporate governance and “poor compliance culture” during his tenure. Kapoor has since sold his entire stake in Yes Bank; the family-owned entity, Yes Capital (India), holds a token 900 shares in the bank. His sister-in-law and co-promoter Madhu Kapur on March 18 sold 2.5 crore shares at ₹65 apiece.

Contagion Effect

The Indian banking sector will have to deal with the contagion effect of the Yes Bank fiasco. “Small regional banks could incrementally find it more difficult to raise deposits. They will not see a strong deposit growth. Small finance banks could also face similar challenges in the coming months,” says Choudhary of Anand Rathi.

Fitch’s Guha agrees. “We have seen deposit flight to safety before, during previous crises in 2008 and 2013. There is a contagion risk particularly on the funding side if the banking sector’s health worsens. These banks could be more vulnerable due to their limited franchise and vintage,” he says. Retail individuals particularly will now opt to park their funds with larger, well-established banks such as HDFC Bank, ICICI Bank and Kotak Mahindra Bank.

The pace of deposit growth is weakening for even new banks, which have showed impressive growth in recent years. AU Small Finance Bank, which was a vehicle finance company in 1996, has seen a fall in the pace of core deposit growth (Casa deposits and term deposits combined). The bank, which commenced operations in April 2017, showed a 63 percent year-on-year rise in deposit growth for Q3FY20 compared to a sharper 295 percent for the corresponding period in Q3FY19.

Similarly Equitas Small Finance Bank, which began operations in September 2016, has shown a slower pace in deposit growth at 42 percent year-on-year in Q3FY20 compared to 79 percent for the corresponding period a year earlier.

IDFC First Bank, led by its managing director and CEO V Vaidynathan, has shown an over-100 percent jump in core retail deposits (Casa and term deposits) for 2018 and 2019. Also, its core retail deposits, as of December-end 2019, constitute 43 percent of total deposits, which goes well with Vaidyanathan’s aim to make IDFC First a focussed retail bank. However, it remains to be seen how the years 2020 and 2021 pan out for the bank, with annual losses and weakening asset quality becoming its major challenges in the near-term.

IndusInd, RBL in trouble?

The mid-sized IndusInd Bank and RBL Bank—once the poster boys of India’s promising banks—are facing the brunt of distress at the stock markets in recent months. The pain has been so acute that the management at these banks have separately made public announcements, highlighting their strong financials.

IndusInd Bank—Yes Bank’s rival in size and profile—has, in just over three months, seen a 71 percent drop in market value to ₹459.8 at the BSE (as of March 18) while RBL Bank has lost 58 percent, trading at ₹166, from around ₹400 levels in early September. Hazari says a weakening stock market price suggests that a nasty surprise might emerge in the months ahead.

IndusInd appears to have crossed one hurdle by getting its succession plan finalised and approved. Its former consumer banking head Sumanth Kathpalia is now the new managing director and CEO for a three-year term. He succeeds Romesh Sobti, who retired on March 23, after leading the bank for over 12 years.

However, after the Yes Bank imbroglio, concerns of IndusInd’s financial health continue to mount, particularly since it has a ₹3,995 crore exposure to debt-laden Vodafone Idea, besides additional exposure to the still-struggling real estate sector and the now-bankrupt IL&FS.

What is worrisome is that IndusInd’s PCR (provision coverage ratio)— which indicates the provision the bank has made for bad loans from its profits—is still low at 53 percent, as of December 2019. This compares to 78 percent for Axis Bank, 71 percent for HDFC Bank and 76 percent for ICICI Bank.

But IndusInd Bank is confident about is financial health. “We have already provided for 73 percent of the IL&FS exposure and this will increase closer to 90 percent in the current [January-March] quarter,” an IndusInd Bank spokesperson tells Forbes India. Regarding the Vodafone exposure, the bank said a package is being developed by the department of telecommunications for the sector’s long-term viability. “That hopefully will be conducive to the welfare of all stakeholders, including banks,” says the spokesperson, adding that the bank will soon unveil its three-year plan.

In the December-ended quarter, IndusInd Bank’s gross NPA stood at 2.18 percent—the second lowest among large private sector banks. “We expect our net NPA of 1.05 percent as of last quarter to fall below 1 percent, in line with our ambition to take provision cover beyond 60 percent,” the bank said.

IndusInd’s exposure toward stressed sectors like non-banking finance companies, construction, real estate, telecom and gems & jewellery has been on a downtrend, with total fund and non-fund-based exposure declining to 14.1 percent in Q3FY20 from 16.7 percent in Q4FY19, says Gautam Duggad, head of research at Motilal Oswal Financial Services. Experts do not see IndusInd Bank going the Yes Bank way.

RBL Bank, meanwhile, in a statement on March 17, defended itself, saying it was “financially strong, well capitalised and profitable”. Commenting on specific concerns, it said there were some withdrawals from institutional depositors and two state governments, constituting about 3 percent of its total deposits in one week. “This issue is being addressed by us on a one-on-one basis with the state governments and also at the industry level by the RBI,” the statement said.

Analyst Choudhary says in RBL Bank’s case, the situation is “not similar or as bad as Yes Bank because it is well capitalised and most of its stressed book [including exposure to Coffee Day Enterprise] is already identified”.

Covid-19 impact

The operating environment for banks, which was already crippled by a credit squeeze, has aggravated due to the impact of the Covid-19 virus. India could have a second order impact, particularly if companies don’t see demand due to weak consumption and economic activity, says Guha from Fitch.

Several corporates have started talking about implementing a business continuity plan. (This is where companies start creating a system of prevention and recovery from potential threats to a company. The plan ensures that personnel and assets are protected and are able to function quickly in the event of a disaster.)

In such a scenario, the retail loans segment—particularly personal loans, loans against property (LAP) and credit card businesses—will bear the brunt first, says Guha. Anand Rathi’s Choudhary says some stress might be seen in LAP and also the LAS (loans against securities) books for banks, considering the sharp erosion in value at the stock markets in the past two months (see: State of Retail Lending Repayments).

Another risk that banks will face relates to vehicle/auto financing on the commercial side, towards Ola and Uber cars in tier II and tier III cities. Driver associations are hopeful that car financiers will now agree to waive off loans for at least two months due to lower earnings and fewer rides.

In such a scenario, Guha believes that most bank managements have a difficult time ahead. Fitch had downgraded the operating environment for banks in India in mid-2019 expecting deterioration following disruptions in the NBFC sector and subsequent credit squeeze by them. The risks have only worsened.

It will make business tougher for smaller banks such as the capital-strapped Lakshmi Vilas Bank or even larger public sector banks that are in the midst of mega-mergers, which Minister of Finance Nirmala Sitharaman had announced in September 2019. Leaders at banks have to face another tumultuous year that they’d want to forget.