Tiger-spotting in Kanha - a paradise for wildlife enthusiasts

Kanha is the quintessential Indian forest, with so much more than the tawny striped big cat

Image: Prasant Krishna

Image: Prasant Krishna

Movement dekhi kya [Did you see any movement]?” our forest guide Murari Patel asks his colleague in an adjacent vehicle as it crosses ours along a dusty track. This is jungle land, and Patel’s question can refer to only one kind of movement—the tiger’s.

Inside the Kanha National Park in Madhya Pradesh, prime land for one of the world’s most endangered big cats—the Bengal tiger has only 2,226 adults of its kind in the wild, according to a 2014 estimate by the National Tiger Conservation Authority—visitors gather every bit of information they can lay their hands on in their search for the often-elusive stripes. Anyone who has been on the tiger’s trail—whether a novice or a seasoned enthusiast—will tell you that spotting the animal in the wild is never easy.

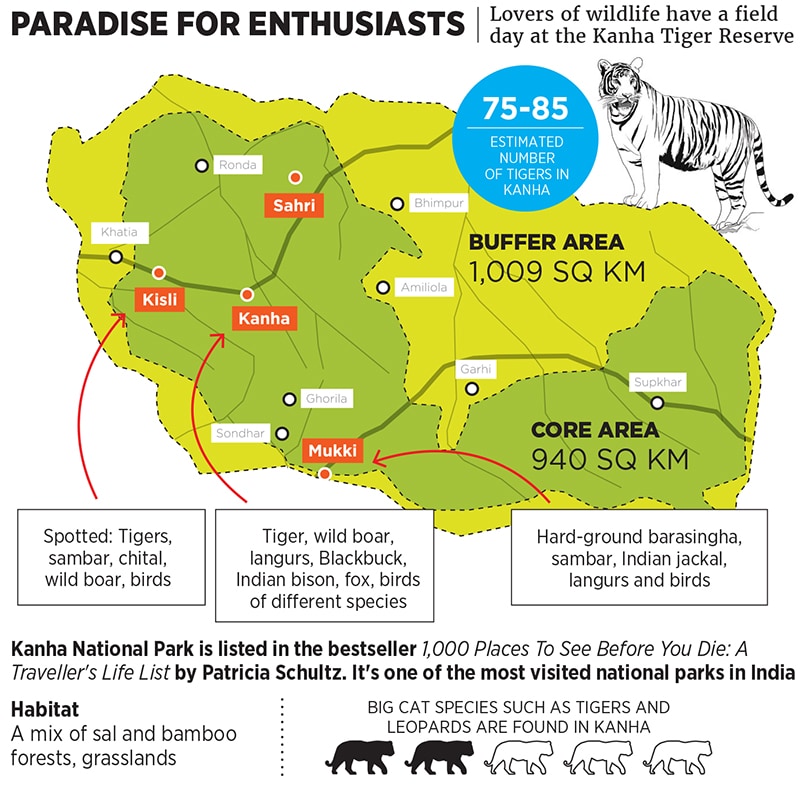

Kanha, which was declared a tiger reserve in 1973 under the country’s ambitious Project Tiger plan, is one of India’s largest tiger reserves, covering 940 sq km. Following the addition of the Phen Wildlife Sanctuary in 1983, along with a large buffer zone (an area around the periphery, or connecting, a protected zone), it now forms the Kanha Tiger Reserve, which covers 1,945 sq km. Alongside the nearby Pench National Park and Bandhavgarh National Park, it forms one of the largest swathes of land in central India where wildlife is largely protected. For example, Kanha has a well-equipped and trained anti-poaching unit, forest guards, fire-fighting staff and administrative teams for the core and buffer zones. As of 2016, India accounts for nearly 57 percent of the world’s tiger population, which is estimated at 3,890, according to WWF and the Global Tiger Forum.

A spotted owlet rests on a tree inside the Kanha National Park in Madhya Pradesh

A spotted owlet rests on a tree inside the Kanha National Park in Madhya PradeshImage: Prasant Krishna

Kanha is vast, and home to mixed forest land characterised by sal trees and bamboo thickets. The flat land is interspersed by wooded hills that have tropical moist dry deciduous vegetation; the lowlands have grassy meadows. The forest, therefore, is not the dense variety you will find in national parks along the Western Ghats or in Northeast India. But this relatively sparse nature of vegetation does not make tiger-spotting any easier.

The tawny, striped cat is generally a solitary hunter, most active during early mornings or late nights. Pug marks in the sand alongside the mud tracks only tell half the story about their location. Once the animal moves into the vegetation, it blends in with the colours of the forest. And along with patience, an equal amount of luck and an enterprising guide or driver increases your chances of tracking the elusive predator.

••

It was early February when we embarked on the tiger’s trail. And despite having spotted, in 2008, one tiger at Kanha and four in Bandhavgarh, my levels of anticipation were as high as a first-time visitor’s. It was that time of the year when the season was beginning to change, and days were getting warmer. But it was still far from the scorching heat of summer when temperatures can touch mid-40 degrees Celsius, and most wildlife—the hunter and the hunted—are forced to frequent the natural and man-made waterholes. Among the wide variety of birds that can be seen at the park is the black-shouldered kite

Among the wide variety of birds that can be seen at the park is the black-shouldered kite

Image: Prasant Krishna

When we set off on our first safari, it was around 3.30 pm. For each of us, it was exciting in different ways: I was back in Kanha after nine years, while my two friends were on their first safari in India, after having trekked the Canadian Rockies and spotting grizzlies, American black bears and wolves in the wild. One piece of advice from my 2008 Kanha guide came back to me: “Do not start trying to click the best photos with your camera. Just observe all the elements of the jungle, soak in everything you see and hear. This will help you click better images later.”

Typical of any national park in peninsular India, the chital or spotted deer were the first wildlife species we saw; small groups, comprising both males and females, were grazing first in the buffer zone and later, in larger groups, deeper in the jungle.

Next were the northern plains grey langurs. We learn from Patel that the chital and the langurs share a symbiotic relationship: Langurs are wasteful feeders, and inadvertently provide the deer with an easy meal of fruits; they are also a great early warning signal—thanks to their perch amid the trees—against predators such as tigers and leopards. The deer, on their part, have a superior sense of smell in locating predators; so when the langurs feed alongside them, they are safe.

The area is full of meadows and vast expanses of grasslands

The area is full of meadows and vast expanses of grasslandsImage: Salil Panchal

As we drove along, within the Singori area of the forest, Patel suddenly became interested in two vehicles that were parked along the track. The visitors in those vehicles were peering to their left, towards a patch of grassland, which gave way to old dead wood and thickets. “Sir, aap ekdum aage dekhiye, uske kaan nazar aayenge (look straight ahead, you will see its ears),” Patel tells us.

We frantically looked through our binoculars, and saw nothing. Then, two white spots or ‘flashes’ (located behind a tiger’s ears) emerged from within the grass. He was lying there, almost motionless, for several minutes, listening to the forest sounds. Then he casually got up, and ambled into the deeper thickets. By then, we were clicking away furiously with our lenses. A few minutes later, another tiger emerged from the same spot amid the grass, and lazily followed the first one into the thickets. If only they knew the frenzy they cause!

The first safari had a satisfying end: Besides the biggest draw, we also spotted the large sambar deer, a small herd of wild boars feeding in the meadows, and blackbucks (which have been reintroduced at Kanha after a successful conservation plan in 2011-12). The safari ended with a fleeting glimpse of a fox.

As I ticked off tigers on the bucket list in my mind, I couldn’t stop wondering: “If we are really lucky, can we now spot a leopard?”

••

The chital or spotted deer shares a symbiotic relation with langurs

The chital or spotted deer shares a symbiotic relation with langursImage: Prasant Krishna

Kanha, being one of the premier tiger reserves in India, has streamlined some of its processes. Now, if a visitor has been lucky to spot a tiger, they are required to write down the details of the sighting—number of people who saw the tiger(s), on which route, at what time, and who the guide was—in a log book at the exit gate. This information gives the guides a rough idea of where each tiger could be over a short period of time, until the animal decides to move into a new area. Over a medium term, this also gives park officials—who also collect detailed data from forest guards and researchers—some idea of how many tigers there could be in the jungle.

All the guides we spoke to estimated that between 75 and 85 tigers could be found in Kanha. This compares to about 70 in Pench and 45 in Bandhavgarh, but in a smaller area, they add. The guides also tell us that cases of poaching continue across most of central India’s parks. Media reports recorded that 33 tigers had been killed in Madhya Pradesh alone in 2016, but experts claim most of these instances were outside protected zones. Kanha’s field director Sanjay Shukla had, at that time, argued that a rise in tiger numbers had led to young male tigers establishing new territories, which had increased cases of man-animal conflict at villages near the national park.

The following day, we set off at the same time in the afternoon for our second safari, this time along the Kanha zone route. We were lucky to spot the hard-ground barasingha (swamp deer), a subspecies now found only in Kanha, and a young gaur (Indian bison) feeding at close quarters.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

Peacocks with open feathers add to the beauty of the place

Peacocks with open feathers add to the beauty of the place It is common to spot a sambar deer wandering in the fields

It is common to spot a sambar deer wandering in the fields