Order, chaos, and emotional intelligence: How Fractal turned unicorn after 22 years

Srikanth Velamakanni and Pranay Agrawal survived a near-death experience and made Fractal into a force to reckon with in the AI and analytics world

Srikanth Velamakanni, cofounder, Fractal

Srikanth Velamakanni, cofounder, Fractal

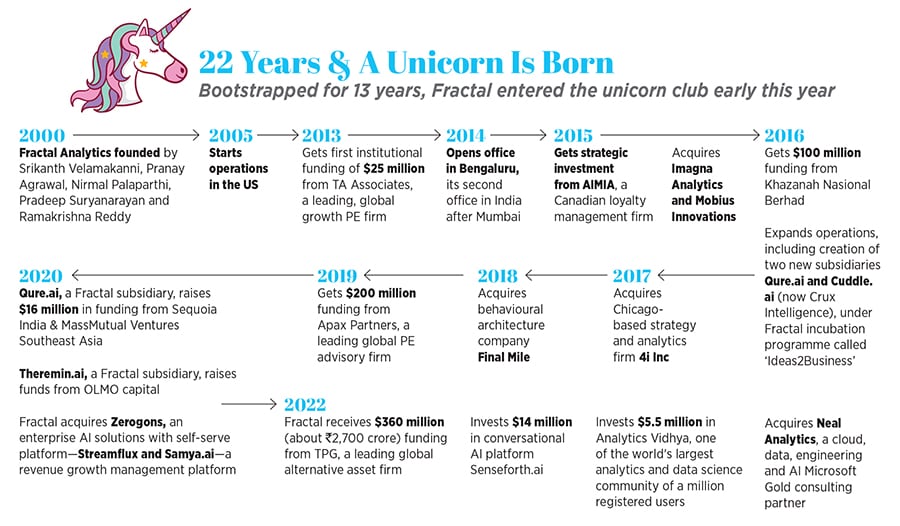

The American musical Chicago was about to start. The theatre was a sea of brightly dressed and disciplined people. There were five Indians, though, on the edge of their seats, all in a celebratory mood, humming with excitement. Six years after starting Fractal in Mumbai, the co-founders—Srikanth Velamakanni, Pranay Agrawal, Nirmal Palaparthi, Pradeep Suryanarayan and Ramakrishna Reddy—had picked a chief executive officer from among them.

The trigger to select the ‘first among the equals’ came from Gulu Mirchandani, founder chairman of Onida Group, and his son Sasha Mirchandani, who had invested in artificial intelligence (AI) and analytics company Fractal as angels in 2001. By 2006, Fractal had grown in size—$2.6 million in revenue, a head count of 60, and global offices in New York and Singapore, and there was a pressing need to have a CEO. ‘Can you guys elect one to scale the company?’ was the message from the angels.

The friends huddled in London—the venue for the elcetion. While Velamakanni and Agrawal came in from New York, Palaparthi and Suryanarayan took a flight from Singapore, and Reddy flew in from India. The election was cordial, and the choice was unanimous. “Everybody was happy, we celebrated and went to watch Chicago,” recalls Velamakanni, who was the new CEO. “For so long, all of us had been equals, but today I was the boss.” It felt weird. “It was not easy, but I tried my best,” he adds. For the next six months, there was perfect order.

Then the descent into disorder began. Fractal’s problem, though, was internal. Differences among the co-founders reached a tipping point, and two of them openly voiced their dissent against the CEO’s working style. The acrimonious row couldn’t be sorted, and there was only one way out: Either the co-founders go back to the old way of functioning, or the company was staring at the imminent possibility of getting vertically split.

Velamakanni and Agrawal conveyed their stand to the investors. “If the company splits,” the duo stressed, “there won’t be two companies. You will get only one dead company.” Eventually, the split did not happen, and Velamakanni continued as CEO.