Monsoon is drawing to a close. Will the Gods show mercy on India's rain deficit?

September rains will be keenly watched as a lower-than-normal monsoon this year has resulted in drought-like conditions in a third of India

With the migration of labour from cities to villages in 2020, there was an increase in sowing in 2020-21.

With the migration of labour from cities to villages in 2020, there was an increase in sowing in 2020-21.

Image: Manunath Kiran / AFP

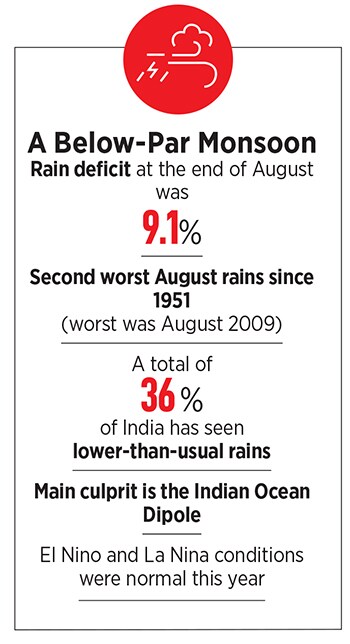

With the final month of the rainy season underway, all that remains to be seen is the final deficit number the country ends up with. The country ended August with a 9.1 percent deficit.

The season started on a good note with normal June rains. July started off weakly, but recovered towards the end. But in August, things started coming apart. “This was the second poorest August we have observed since 1951, with August 2009 being the poorest,” says GP Sharma, president (meteorology) at Skymet Weather. The month recorded a 24.1 percent deficiency.

Sharma says it is unlikely this deficit can be made up in September and there will almost certainly be a below-par monsoon number. He cites the Indian Ocean Dipole, which is an irregular oscillation of sea surface temperatures in the western Indian Ocean, as the main culprit. A total deficit of 10 percent or more is termed a drought.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

Second, in states like Punjab, Haryana, Kerala and the Northeast, lower rains matter little as irrigation systems and groundwater supplies make up the shortfall. As a result, staples like rice and wheat are unlikely to see lower production.

Second, in states like Punjab, Haryana, Kerala and the Northeast, lower rains matter little as irrigation systems and groundwater supplies make up the shortfall. As a result, staples like rice and wheat are unlikely to see lower production.