Zomato: Betting the farm

How food tech major Zomato is making an audacious bid to transform itself into a farm-to-fork company

“We are trying to transform Zomato into a foods company, much like a farm-to-fork model. The goal is to have fresh and clean food for all.” -Deepinder Goyal, co-founder, Zomato

“We are trying to transform Zomato into a foods company, much like a farm-to-fork model. The goal is to have fresh and clean food for all.” -Deepinder Goyal, co-founder, ZomatoImage: Amit Verma

Lakkondahalli village, Bengaluru rural district: Lokesh’s day in the fields begins at 3 pm. Over the next few hours, his wife Manjula and he harvest a variety of agri-produce, from red amaranth, spring onion, suva and curry leaves, to coriander leaves fenugreek, mint leaves and spinach. It’s then time to sort the produce as per the grading specified by their buyers. By late evening, the husband-wife farmer duo loads the Chota Hathi (small elephant), a Tata Ace mini truck with roughly 300 kg of the produce it has harvested since afternoon.

Every night, Lokesh drives over 30 km—an hour and a half from Lakkondahalli village—to transport his agri-produce to a warehouse in KR Puram, a suburb in Bengaluru.

At 30 minutes past midnight, the 7,000 sq ft expansive warehouse is awash in white light. The depot has clearly demarcated rows for groceries, dairy products, flour and rice. Stacks of onions and potatoes, neatly wrapped in red and brown sacks, are meticulously placed on the left. Towards the rear are three big cold rooms. The one operating at 0-4 degree Celsius keeps poultry; vegetable and fruit find a place in the adjacent room at 8-12 degrees; and frozen meat is in the last room at -18 to -22 degrees.

Lokesh begins unloading the Chota Hathi. A battery of workers starts to sort the produce in the manner prescribed in the manual prepared by Dhayalan Paul, head of quality at HyperPure, the company that owns the warehouse. “Spinach to be packed in bunches of 250 gm. Look for spoilt leaves, dirt and mud,” Paul instructs the boys, who are clad in HyperPure-branded tees, their heads covered with white stretchable caps. The packing finishes by 4 am, ready to be transported in batches to restaurants in Bengaluru.

“All our ingredients are sourced based on FSSAI (Food Safety and Standards Authority of India) parameters and only from manufacturers, growers and importers who have FSSAI licences,” says Paul, turning his attention to Lokesh who walks past a big hoarding of HyperPure at the entrance of the warehouse. He doesn’t seem to notice the branding in small letters of Zomato Internet Private Limited, written below HyperPure, as he gets ready to take his Chota Hathi back to the village.

“I know Hypercity, Safal and WOTO, who used to buy produce from me,” says Lokesh. Though he does know HyperPure, which was earlier WOTO (We organise the unorganised) and recently bought by Zomato and rebranded HyperPure.

Image: Hemant Mishra for Forbes India

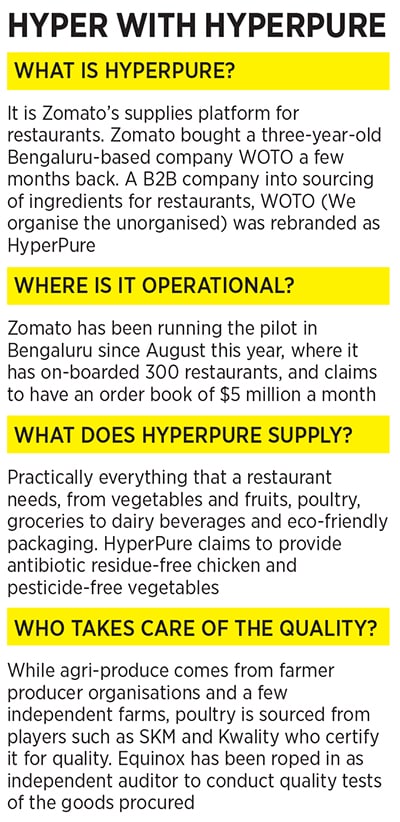

Welcome to Bengaluru where food tech major Zomato is making an audacious bid to transform itself into a farm-to fork-company with HyperPure. A supplies platform for restaurants, HyperPure practically sells everything that a hotel needs: From vegetables and fruit, poultry, groceries and spices to dairy beverages and even eco-friendly packaging.

The goods are procured directly from the source. Vegetables, for instance, are sourced from small independent farmers and FPOs (farmer producer organisations) that don’t use pesticides. Poultry is procured from farms that ensure that the chicken is antibiotic residue-free. Big-ticket grocery items come directly from the big consumer companies. To ensure that quality standards are adhered to, Zomato has roped in Equinox Labs, an independent food quality auditing firm, with the mandate to regularly test samples.

“We are trying to transform Zomato into a foods company, much on the lines of a farm-to-fork model,” says Deepinder Goyal, co-founder of Zomato, which started in 2008 as a food discovery and ratings platform. The intent, he lets on, is not only to supply ‘clean’ and ‘fresh’ produce to the restaurants but also make a strong business proposition out of it.

Goyal explains how. What HyperPure sells to merchants, he stresses, is not just antibiotic residue-free poultry, pesticide-free vegetables and high-quality groceries but also the proposition that the restaurants get certified on Zomato’s web page for using such ingredients. “Consumers will buy food for the sticker that assures high quality and safety,” he reckons, adding that it’s a win-win for restaurants and consumers.

The Gurugram-headquartered company is betting big on the high level of awareness among Indians about abuse of antibiotics by poultry producers. Early this year, the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) reiterated that antibiotic use in poultry sector is rampant in India. “They (producers) are even using life-saving drugs like colistin to fatten chicken. There seems to be no genuine attempt by the industry to reduce antibiotic misuse,” Chandra Bhushan, deputy director general at CSE, reportedly said.

Goyal senses a business opportunity. “Why would people not eat antibiotic residue-free chicken?” he argues. “You eat to live, not to die, right?” he asks, pointing out how global companies have made big fortunes in the business of sourcing and supplying clean and healthy products for restaurants.

Take, Tyson Foods, for instance. The American company is the world’s second largest processor and marketer of meat. Out of $38.3 billion sales posted in FY17, chicken was the second biggest source, accounting for 30 percent of sales. A third of sales came from food service players, which means restaurants.

Image: Hemant Mishra for Forbes India

“Look at Sysco,” says Goyal, dishing out another example he would love to emulate. The world’s biggest distributor of food and related products such as fresh and frozen meat, fruits, vegetables, dairy, beverage, and paper products, Sysco clocked sales of $59 billion and a gross profit of $11.1 billion in the fiscal ended June 2018 by selling to restaurants and other business establishments. “The opportunity on the supply side of the food business is massive,” he asserts, adding that HyperPure is a perfect mix of B2B and B2C.

What gives Goyal the confidence is the demand experienced during the first month of the pilot rolled out in August this year. With 300 restaurants on board, HyperPure managed an order book of $5 million a month, but ran out of farms within two weeks. The company had to stop supply temporarily as it couldn’t meet the demand. “It’s a flywheel. Demand pushes the supply, which in turn creates demand,” Goyal smiles.

Zomato is trying to fix the supply side by reaching out to farmers and guaranteeing them that it will buy their produce if it’s clean. A lot of farmers, Goyal reckons, are ethical. Financial pressure and lack of predictability of demand force them to go lax on quality. “Nobody wants to produce bad stuff. People do it because they have to, not because they want to,” he argues. Taking care of the demand side fixes a large part of the problem.

What might also be a comforting factor for Goyal is the American trend of spending more on restaurants than on groceries. Restaurants are fast becoming the preferred choice for people to get their three meals in a day. “It has been happening in the US. I don’t see why it can’t happen in India,” Goyal maintains. “If we crack three As—accessibility, affordability, assortment—and quality, it takes away the reason to cook at home.”

In a December 2017 report titled ‘What’s cooking with Indian diners’, Nielsen maintained that affluent Indians—those with an annual income of over ₹10 lakh—spend approximately twice as much as their middle-class counterparts on eating out every year. Millennials in the middle income segment—earning between ₹3 lakh and ₹10 lakh per annum—spend 10 percent of their total food expenditure on eating out. “On an average, urban Indians spend ₹6,500 per year on eating out,” the report pointed out.

Though urban millennials and Gen X consumers (35-50 years), unlike their American counterparts, still spend more on groceries than eating out, for the former, the ratio of average expenditure on eating out compared to the spend on groceries is two-thirds, Nielsen highlights. “Clearly, eating prepared, cooked food is now a convenient proposition for urban consumers and millennials alike,” the report concluded.

Eating out is complemented by a heady rise of another trend: Food delivery. Those who are not stepping out are eating at home, but not a home-cooked meal.

The food delivery market in India is likely to grow seven-fold in seven years—from $1 billion in 2018 to $7 billion by FY25, according to an August report by Goldman Sachs. What’s fuelling the growth are convenience, ease of ordering, live tracking of delivery, increasing penetration of smartphones and the growing number of working women in India. “The online food market can grow to 100 million orders per month in FY23,” projects the report.

A boom in food delivery has the potential to expand the entire food market. Take, for instance, the restaurant dining market, which is estimated to leapfrog from $13 billion in FY18 to $28 billion by FY25. This will have a cascading effect on the unorganised food market, which is set to balloon from $33 billion to $53 billion during the same period, according to Goldman Sachs.

The changing dynamics of food delivery and eating out are reflected in the way Ant Financial-backed Zomato has been growing over the last three years. Delivery, which made up just 4 percent of revenue in FY16, surged to 65 percent by the end of September this year and is pegged to be the biggest growth driver for Zomato; it’s expected to climb to 72 percent by FY21.

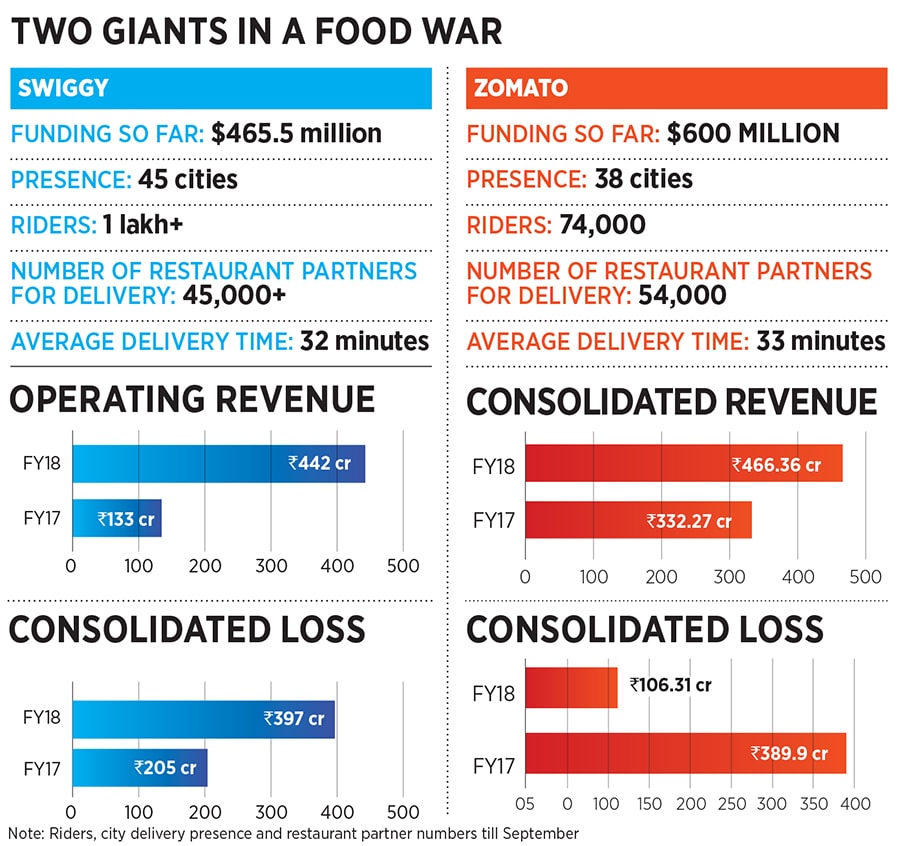

The surge has put the food-tech company on a hyper-growth trajectory. While consolidated revenue jumped from ₹183.95 crore in FY16 to ₹466.36 crore two years later, losses have dipped from ₹590 crore to ₹106 crore. Operating burn too has reduced from ₹425 crore to ₹92 crore. “We forecast Zomato revenues to grow by 500 percent in three years,” Goldman Sachs predicted in its report.

The pace of growth has only gathered steam this year. From being present across 15 cities for food delivery this January, Zomato expanded its reach to 38 cities by September. The target is 100 cities by end of November. A fleet of 5,400 delivery riders in January has swelled to 74,000 riders by September. The strength of restaurant delivering partners has almost doubled from 28,000 to 54,000 during the same period.

Back in Bengaluru, Dhruv Sawhney is busy signing on restaurants for Zomato’s new venture. The head of procurement and sourcing operations for HyperPure, Sawhney was the founder of WOTO.

“Sourcing is an operational nightmare for restaurants,” he points out. From inconsistency in quantity and quality of ingredients to unreliability in delivery of the products to wastage and pilferage, operational challenges—which are not even related to cooking—take up most of the time of restaurants. HyperPure, he claims, has been streamlining the supply chain by getting everything under one shop. “We even forecast demand for restaurants using machine learning. This eliminates the need for overstocking,” he says. And fixed pricing for a monthly duration allows better planning and competitive prices for owners.

Lokesh Krishnan agrees. Owner of the online delivery biryani brand Potful, Krishnan is one of the first clients of HyperPure. “It’s convenient. Everything that we need is available on one platform,” he says, listing out other benefits: Insulation from price fluctuation, ample choice in terms of assortment of chicken and predictability of demand. What’s surprising though is that antibiotic residue-free chicken was not the biggest pull for the biryani player. “What matters most is peace of mind in getting things efficiently and hassle-free,” he says.

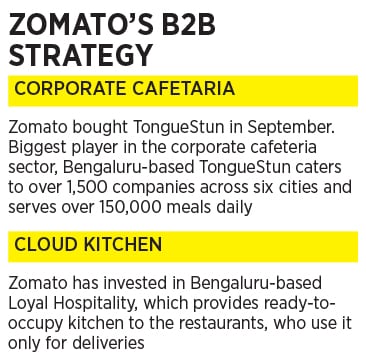

Sourcing, reckon food experts, is a massive opportunity yet to be tapped by any organized player in India. “It’s a timely move by Zomato,” says celebrity chef-cum-entrepreneur Sanjeev Kapoor, “which will help it differentiate from others.” Though sourcing of food and ingredients for restaurants is a big business globally, in India it is still at a nascent stage. “HyperPure is the best way Zomato has spent money so far,” he says.

The challenges for Zomato, though, are daunting and manifold. Kapoor starts with the biggest one. “The business itself is the biggest challenge,” he says. The complexity of the task is huge, it’s not a business that Zomato has any experience in, and there is no guarantee that leveraging its existing strength of food discovery and delivery will work in food sourcing as well. “It’s not easy for somebody who has been selling biscuits to a shop to go and tell them that you will now also supply milk, vegetables, rice and groceries,” he cautions. Another challenge for Zomato is its inability to develop an enduring relationship with chefs. “They have a huge role to play in deciding the source from where goods are procured. Zomato, unfortunately, never built any relationship,” Kapoor adds.

Another issue to contend with is the margin structure of restaurants, which is abysmally low. “In most cases, poor store economics lead to payment defaults. Zomato will have to figure out a way to protect itself from credit risks,” warns Jaspal Sabharwal, co-founder of TagTaste, a collaborative network for food professionals. The HyperPure gambit, he adds, will pay off only if Zomato keeps educating consumers and explaining to them why they are paying a premium.

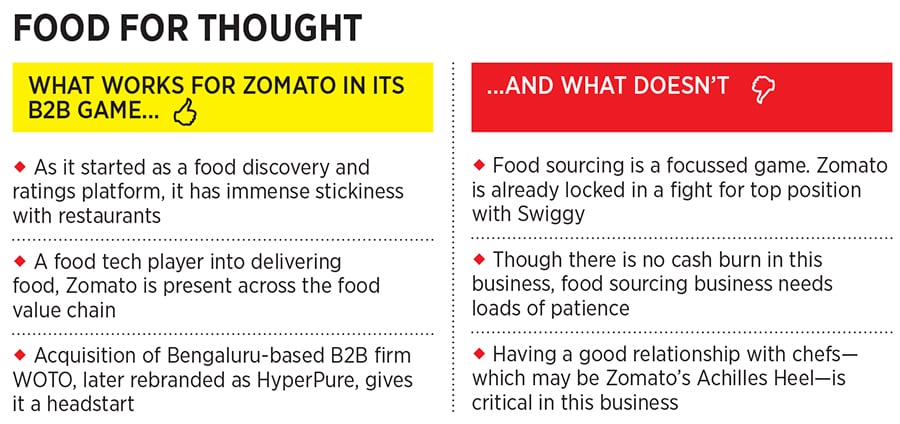

Operational issues notwithstanding, what might turn out to be the biggest challenge for Zomato is the threat from archrival Swiggy. Zomato is locked in an intense battle for supremacy with the Naspers-backed food-delivery company headquartered in Bengaluru. With over 45,000 restaurant delivery partners, 1 lakh active riders across 45 cities, and over $465 million funding raised so far, Swiggy has been breathing down Zomato’s neck.

What makes the fight interesting is the pace at which Swiggy is growing: From an operating revenue of ₹133 crore last fiscal to ₹442 crore in the March ended 2018 fiscal, a three-fold jump. Though losses too have leapfrogged—from ₹205 crore to ₹397 crore—it’s not something that Swiggy might worry about. Reason: The backing of South African media conglomerate Naspers, which has a 22 percent stake in Swiggy, as of March.

In an exclusive interview to Forbes India in September, Naspers CEO Bob van Dijk made his intentions clear. “Swiggy’s business has grown 4x in a year. It’s spectacular. It’s already the biggest in India,” he said, adding that Swiggy would keep its aggression intact. “My hopes and aspirations for Swiggy are high,” he added. “Opportunity in food delivery is at least 50 times bigger than where it is today.”

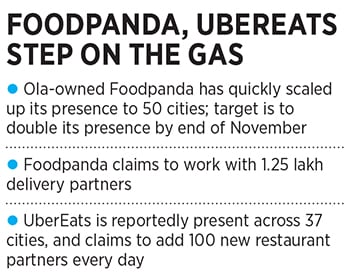

Swiggy, for its part, is firm in not taking its feet off the pedal. “We will continue to double down on this growth as we expand to more cities,” says a Swiggy spokesperson in an email reply. In just four years, the spokesperson added, Swiggy has become a household name. Last fiscal, the company stayed focus on improving operational efficiencies. “This has resulted in the operating revenue increase (a 232 percent increase) outpacing the cost increase, further strengthening our position,” the spokesperson writes. And don’t forget that Zomato also has to contend with Ola-owned Foodpanda and UberEats.

But it’s the head-on battle with Swiggy that can affect Zomato’s HyperPure plan. Reason: Food sourcing needs a focussed approach, and loads of patience. As both rivals dig deeper into the bleeding game of delivery, it might hurt Zomato more with the focus on HyperPure getting diffused.

Back in Gurugram, the competition doesn’t appear to be on Goyal’s radar. “We would rather focus on our work than think of what rivals are doing,” he says, as he takes a sip from a glass of fresh tomato juice and points to a poster plastered on one of the walls of his corporate headquarters. ‘July 10, 2008. We were born. July 10, 2013. We started walking. July 10, 2018. Now is when we start running’, it reads. “It’s time to put on the running shoes,” Goyal signs off.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

X