Sarvam AI: Building generative AI a billion Indians can use

With the belief that India should have its own sovereign AI stack, with the agency to run it and the expertise to build it, Pratyush Kumar and Vivek Raghavan are building Sarvam AI

Vivek Raghavan (left) and Pratyush Kumar, Cofounders, Sarvam AI

Image: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India; Digital imaging: Kapil Kashyap

Vivek Raghavan (left) and Pratyush Kumar, Cofounders, Sarvam AI

Image: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India; Digital imaging: Kapil Kashyap

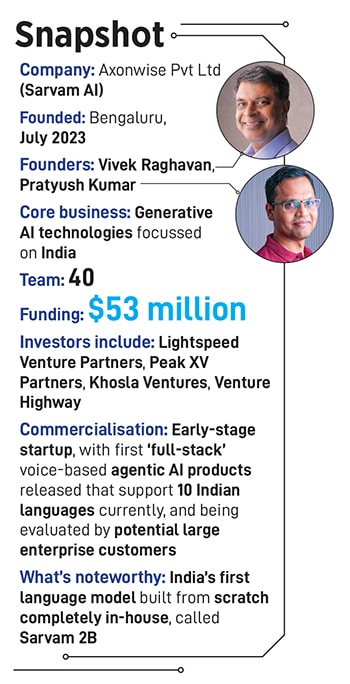

Sarvam AI, which is seen in India’s tech circles as the country’s torchbearer in the world of GenAI (generative artificial intelligence), is only about a year old if one goes by the date it was incorporated as an Indian company.

However, Axonwise Private Limited, the company’s legal entity, has already raised $53 million—via a seed round followed by a Series A investment last year—from investors, including Lightspeed Venture Partners, Peak XV Partners, Khosla Ventures and Venture Highway. A select few corporate and angel investors are also on board.

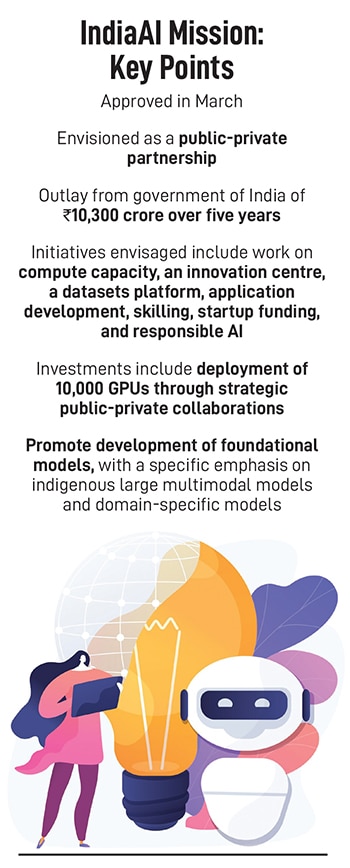

One important reason such high-power backers have decided to fund Sarvam is that it is among a precious few ventures in the country to be working on their own foundation-level AI tech. That means they’re building the core elements that make up their own GenAI systems, including the algorithms, architectures, training techniques, curated datasets and so on, all leading to their own GenAI technologies on which they as well as others can build useful applications.

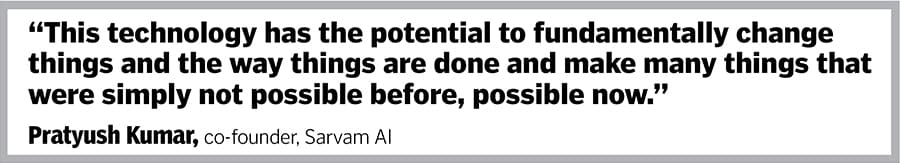

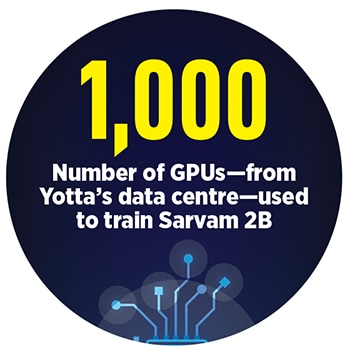

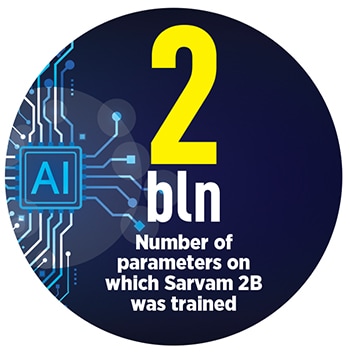

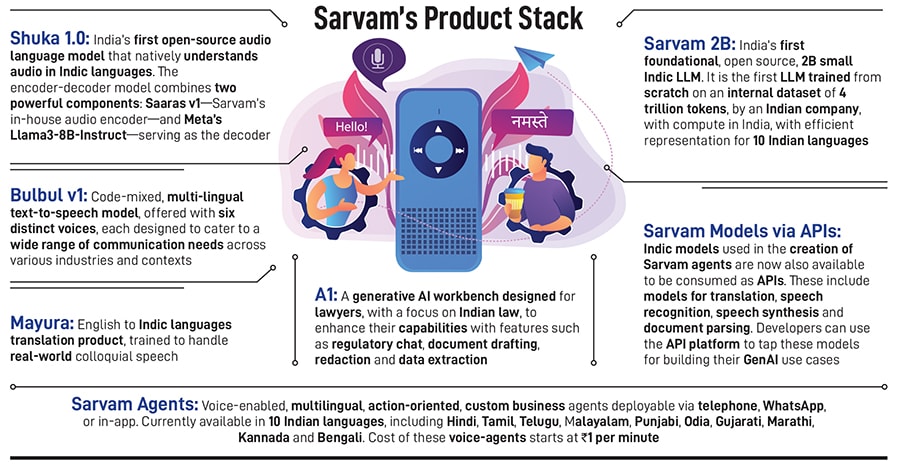

The company has released a raft of voice-based AI tools for enterprise customers, addressing some of the most common use cases, and an open source text-based language model, named Sarvam 2B, given that it was trained on 2 billion parameters, with an emphasis on Indian languages. “The intention was that India should have its own sovereign stack of AI. By that we mean not just the agency to run it, but also the expertise to build it,” says Pratyush Kumar, one of two co-founders of Sarvam.

The aspiration at Sarvam, as the word Sanskrit meaning ‘all’ suggests, is to achieve in AI something akin to what the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) has done in payments and fintech in the country: “We want to build GenAI that a billion Indians can use,” explains Vivek Raghavan, the other co-founder.

The aspiration at Sarvam, as the word Sanskrit meaning ‘all’ suggests, is to achieve in AI something akin to what the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) has done in payments and fintech in the country: “We want to build GenAI that a billion Indians can use,” explains Vivek Raghavan, the other co-founder.

(This story appears in the 04 October, 2024 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

Parameters are what the AI models are trained on. They define how the models transform inputs and provide outputs such as text completion or predictions and so on. Then there are tokens, which are discrete units of text. They can be words, sub words, characters and so on. Tokens are the data that the models take as inputs.

Parameters are what the AI models are trained on. They define how the models transform inputs and provide outputs such as text completion or predictions and so on. Then there are tokens, which are discrete units of text. They can be words, sub words, characters and so on. Tokens are the data that the models take as inputs.  Kumar and Raghavan say Sarvam’s models are efficient with Indian languages. And they can be used for a variety of tasks such as in speech models, translation, colloquialising an input given and other narrow, but specific use cases that have practical value in the real world.

Kumar and Raghavan say Sarvam’s models are efficient with Indian languages. And they can be used for a variety of tasks such as in speech models, translation, colloquialising an input given and other narrow, but specific use cases that have practical value in the real world.

Earlier on, he also worked as chief AI evangelist at EkStep Foundation, the non-profit organisation backed by Nandan Nilekani and his wife Rohini. He remains an advisor on technology to UIDAI.

Earlier on, he also worked as chief AI evangelist at EkStep Foundation, the non-profit organisation backed by Nandan Nilekani and his wife Rohini. He remains an advisor on technology to UIDAI.