Are Lakshmi Vilas and Dhanlaxmi Bank cases of shareholder activism gone wrong?

Regulators have been keen to cap shareholding limits in institutions, be they promoters or individuals, to improve governance. But this has only caused splintered shareholding and new problems

(From left) S Sundar, managing director and CEO, Lakshmi Vilas Bank and Sunil Gurbaxani, managing director and CEO Dhanlaxmi Bank

(From left) S Sundar, managing director and CEO, Lakshmi Vilas Bank and Sunil Gurbaxani, managing director and CEO Dhanlaxmi Bank

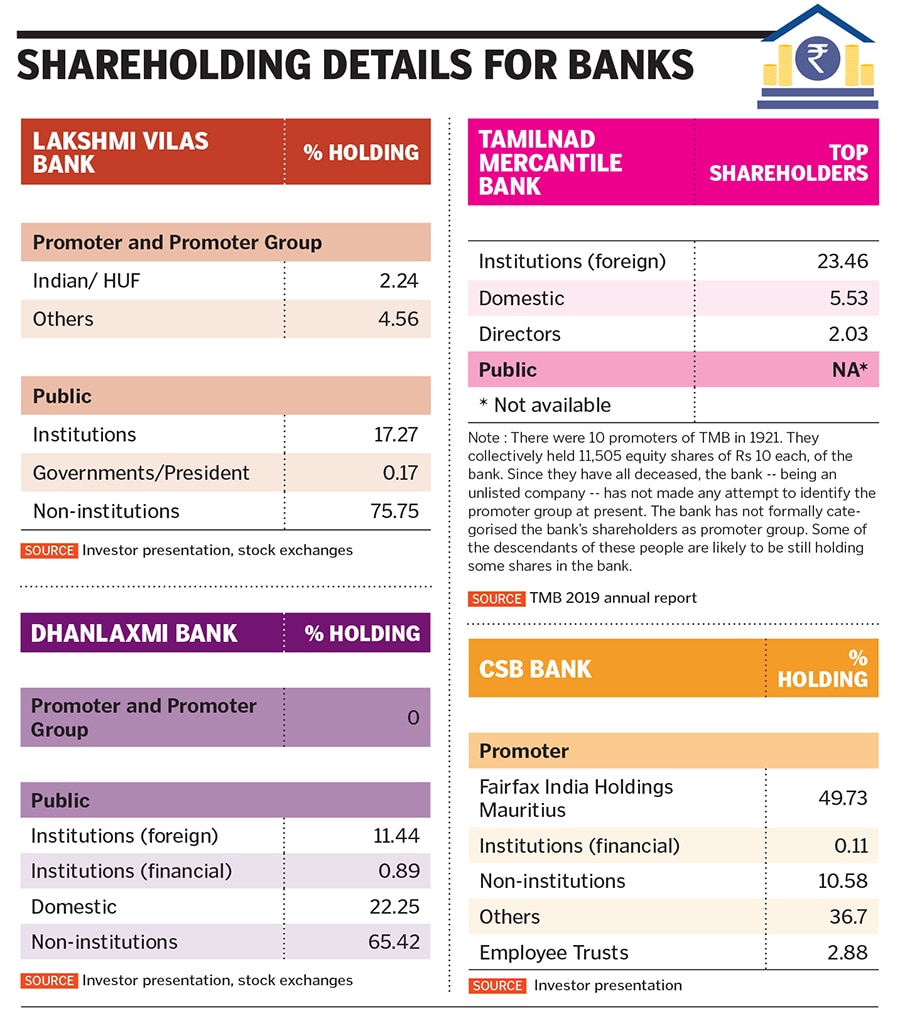

In recent weeks some of India’s large private banks have been jolted out of their daily humdrum, their leadership ousted by a small group of activist shareholders who stormed in to exercise control. While protection of minority shareholders’ rights and – depositors, in the case of banks – has been the predominant trigger to cap shareholding levels in an institution, these recent instances suggest that there might be a need for the regulator to rethink a few norms.

Last month, the managing director and CEO of two private banks, Lakshmi Vilas Bank’s (LVB) S Sundar and Dhanlaxmi Bank’s, Sunil Gurbaxani were cast out, bringing these already weak banks to their knees and making their future even more uncertain. In both cases, a small section of shareholders decided to exercise their power to vote out or act against individuals who they thought were detrimental to the interest of the bank.

A few years ago, the Tuticorin-headquartered private sector bank TamilNad Mercantile Bank suffered when a small community of its shareholders voted against a resolution to make the bank a listed entity at the AGM in January 2016. This debate for an initial public offering (IPO) continues to remain stalled.

In the current decade, India has seen the mushrooming of proxy firms which play an active role in advising institutional investors – who were often active only in mergers and acquisitions or raising capital – to exercise their voting rights. These have resulted in high profile debates between shareholders and promoters/directors at the board level. “For the smaller banks, it is in the shareholders’ interest that they don’t allow the cadre to develop at all. The activism can be confined to just 1-2 people,” says a banking consultant, who has been on the board of several private banks, declining to be named.

Splintered shareholding