Car rides, canteen visits, and unlocking value: Inside the Ajit Dayal and Subbu way of investing

Over the 25 years they have worked together, Ajit Dayal and IV Subramaniam of Quantum Advisors have built processes that put integrity at the heart of what they do. And a part of the process also involves sitting around in company canteens

IV Subramaniam (left) and Ajit Dayal of Quantum Advisors have built processes that put integrity at the heart of what they do

IV Subramaniam (left) and Ajit Dayal of Quantum Advisors have built processes that put integrity at the heart of what they do

Image: IV Subramaniam by Neha Mithbawkar for Forbes India

The year was 2007. Everyone was gung-ho about the world; markets were establishing new peaks. Ajit Dayal was on the road raising money for international investments in India. But when he met people, he told them to hold on, that they should not be allocating too much money to India, and to give his company only 20/25/33 percent of what they wanted to eventually give him. “But you’re an India manager, you’re looking for business and AUM [assets under management], and you’re telling us not to buy India,” investors told him, recalls the founder of investment firm Quantum Advisors. But it was their assumption that India was overvalued then, and they told clients, “We’ll call you when the markets collapse.”

Obviously, in 2008, when the Lehman crisis hit, Dayal and his team made the calls.

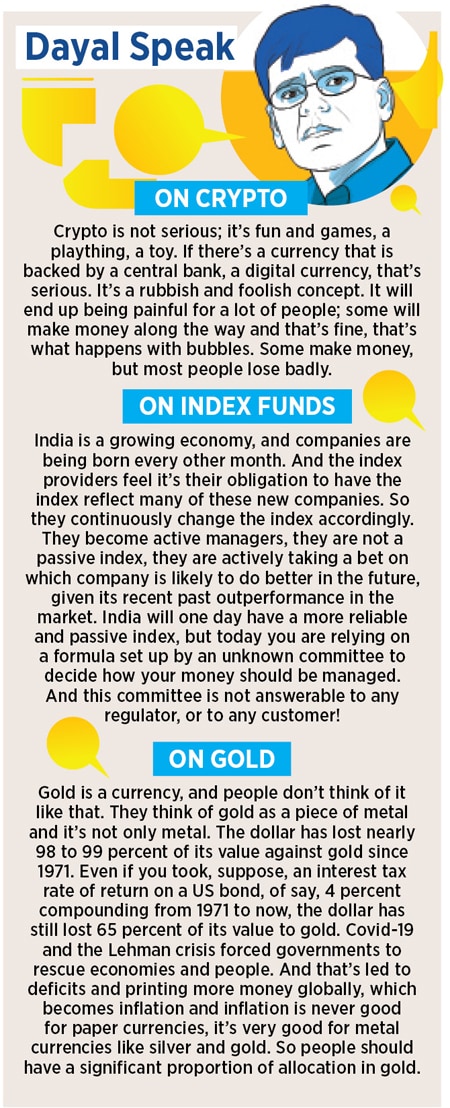

About 14 years and a few peaks and troughs later, the markets are at some sort of a peak yet again. And the obvious question you ask the man who has been in the business since the ’90s is: Do you think the markets are overvalued? “Currently, markets are certainly not inexpensive. I don’t know if they’re overvalued,” he says. It’s a dynamic situation in the short term, depending on whether Covid-19 drags on or if it disappears quickly. “But on a five- seven-year view, India will give you a rate of return that’s very respectable as an international investor, and certainly, as a domestic investor you should be invested in equities for the long haul,” he says, on a Zoom call from Europe.

With small businesses being affected and unemployment rising, the situation might not be ideal for society at large, but consumption demand will move to larger companies and it is this value that the team at Quantum is looking to try and unlock.