- Home

- UpFront

- Take One: Big story of the day

- Charged up: Inside Ola's audacious electric gambit

Charged up: Inside Ola's audacious electric gambit

From setting up an EV factory in six months to fixing initial glitches on a war footing to topping the EV two-wheeler chart for over 12 months in a row, Bhavish Aggarwal is a man in a tearing hurry. The maverick founder is now ready with a high-risk, high-return plan—EV batteries, cars and three-wheelers. Can he do it?

Rajiv is based out of Delhi-NCR and writes stories on startups, corporates, entrepreneurs of all kinds, and yes, marketing and advertising world. His ‘historic feats’ include graduation in history from Hansraj College, master's in medieval Indian history from Delhi University, and PG diploma in journalism from Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. Another forgettable achievement was spending over a decade at The Economic Times as his maiden job. For the first seven years, he learnt the craft on the desk, and the remaining years were spent unlearning and writing for Brand Equity and ET Magazine. What keeps him going, and alive, apart from stories is the heavenly music of immortal legend RD Burman.

Bhavish Aggarwal, founder and CEO, Ola Cabs & Ola Electric

Image: Selva Prakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India

Bhavish Aggarwal, founder and CEO, Ola Cabs & Ola Electric

Image: Selva Prakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India

Electrifying speed inevitably produces two kinds of reactions. The first is ‘shock’. And the second ‘awe’. Bhavish Aggarwal is more than familiar with both the turbo-charged emotions. In fact, the IIT-Bombay alum has had multiple encounters with disbelief and scepticism during his fast-paced entrepreneurial journey, which started in 2010 when he rolled out ride-hailing venture Ola. Over a decade later, though, Aggarwal prefers to talk about the not-so-recent past. He takes us back to the beginning of 2021. “When we bought land for Futurefactory, everyone said that we won’t be able to build it,” says the founder who decided to get into the business of manufacturing electric two-wheelers.

Related stories

The move triggered widespread shock, scoff and jibes. “It’s not an app. He has to make vehicles, and he doesn’t have the background,” were common reactions. “It’s one wild experiment, and will end up like Ola Café, Foodpanda, Ola Cars and Ola Dash,” was another set of backlash, which emanated from Ola’s track record of exploring multiple things at multiple times, and then eventually folding them up.

For instance, a year after its launch, Ola Café was shut down in early 2016. Three years later, in 2019, Ola shuttered Foodpanda, which it bought towards the end of 2017. In June last year, Ola halted operations of its used-vehicles business, Ola Cars, and quick commerce venture Ola Dash. The critics got the much-needed fodder from a repetitive script which played out in a predictable manner: A promising start and a disappointing end. “Can he do any other stuff apart from cabs?” they asked. “Why can’t he just stick to one business and grow it?”

Aggarwal, for his part, was merely following his heart, and DNA. “I’m a very curious person. I have a broad set of interests,” says the founder, explaining the trigger behind a bunch of his daring bids at various points of his career. “And I feel that every interest must be explored.” So, in February 2021, the plucky founder announced his grandest plan: Building electric two-wheelers. In terms of reactions, there was no surprise. “Can he do it?” observers asked in disbelief. Over two years later, Aggarwal has an answer. “We built it in six months,” he underlines.

Also read: 'If they have OATS for breakfast, I put ICE cubes in my drink': Ola's Bhavish Aggarwal

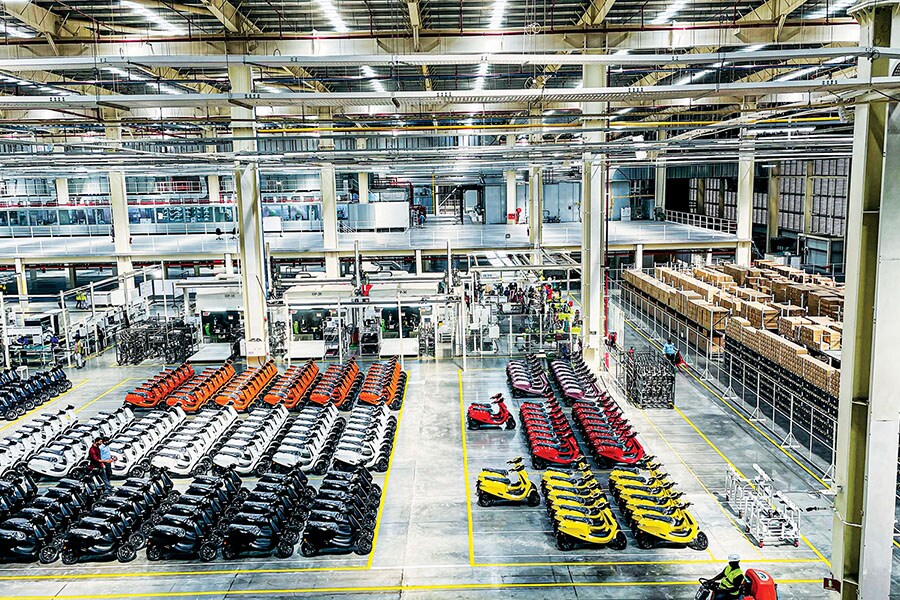

The scepticism, however, stayed unabated. “People said we won’t be able to make a product,” recounts Aggarwal. “We did it.” The Futurefactory at Pochampalli in Tamil Nadu, he lets on, has an installed capacity of 2 million units a year, and plans are to ramp it up to 10 million units. While the current capacity is 1 million, it is being cranked up to 2 million by the end of year. The next question was: Will he be able to sell? “We sold,” says Aggarwal, adding that Ola Electric has sold over 3 lakh scooters so far.

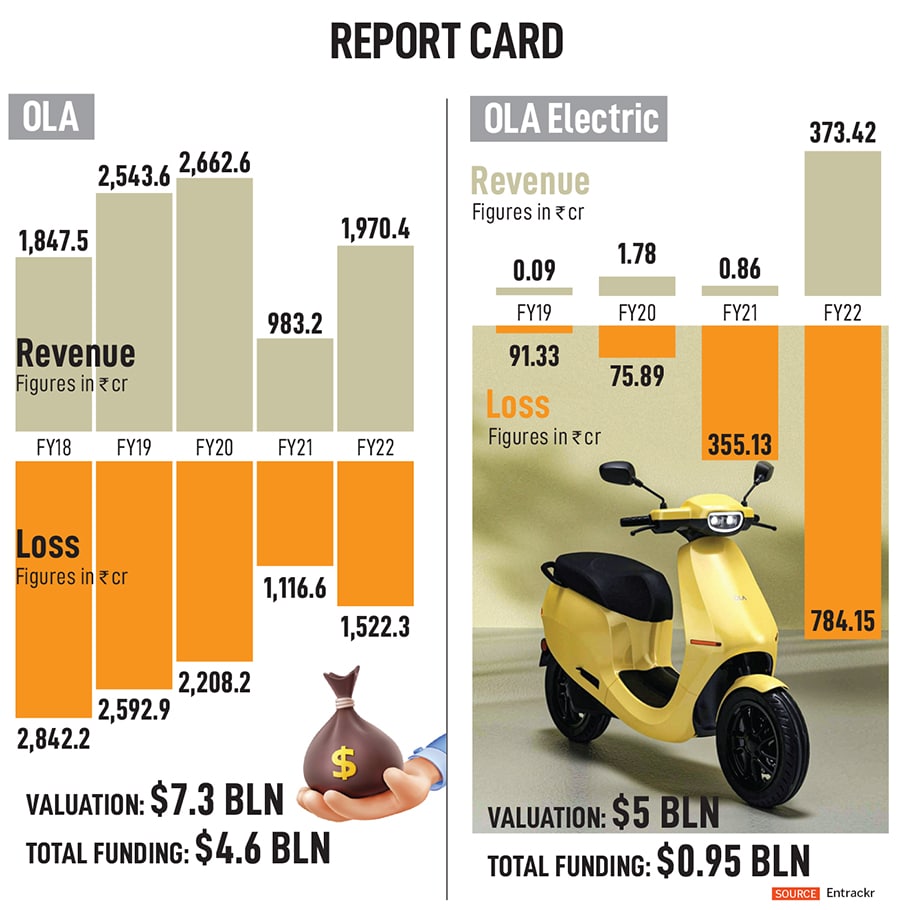

The stream of questions, though, kept flowing relentlessly. “How will the company make money?” was the new query. Though the company started deliveries of two-wheelers from December 2021, the operating revenue of the preceding three fiscals didn’t give any room for comfort: ₹0.09 crore, ₹1.78 crore and ₹0.86 crore in FY19, FY20 and FY21, respectively, according to data accessed from Entrackr’s TheKredible, a data intelligence platform. The loss during the same period was ₹91.33 crore, ₹75.89 crore and ₹355.13 crore.

In FY22, though, the picture changed drastically. Ola Electric posted an operating revenue of ₹373.42 crore and a loss of ₹784.15 crore. “When we file for our IPO, they (critics and naysayers) will see our business model,” says Aggarwal, who is quick to point out a few more questions. “Okay, they are selling. But can they scale? Can they take on the big boys? Can they become Number 1?”

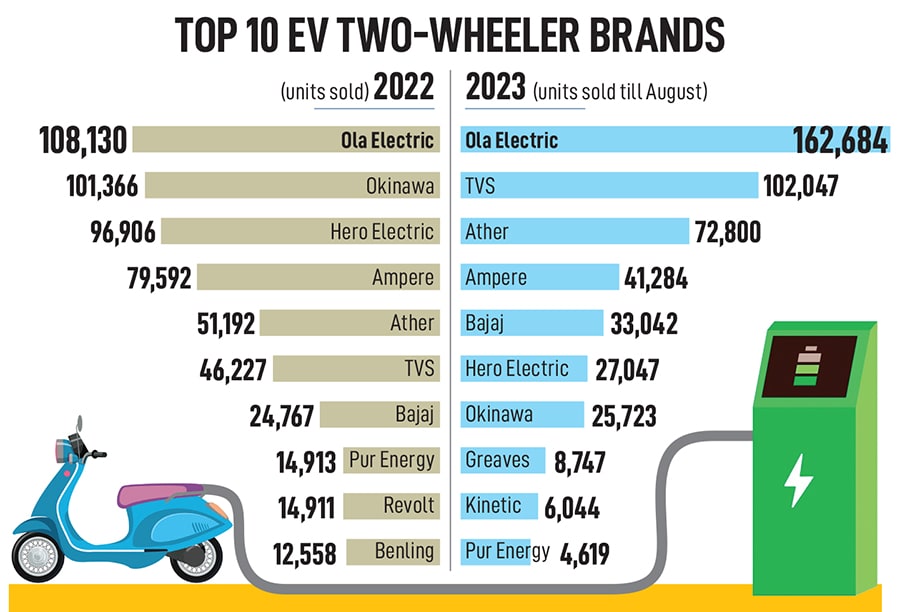

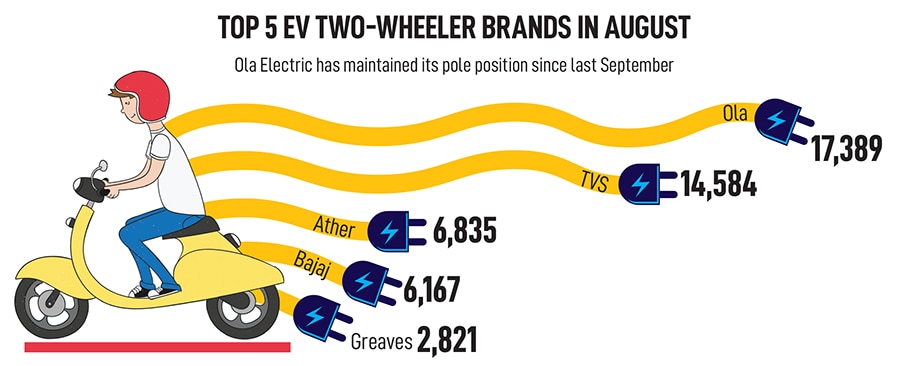

The answers, Aggarwal says, lie in the sales data. For over 12 consecutive months, Ola Electric has maintained its top billing and has emerged as the biggest electric two-wheeler player in India in terms of volume. While the brand sold over 1.08 lakh EVs in 2022, in the first eight months this year, it briskly outstripped the numbers it posted last year by selling over 1.62 lakh two-wheelers. In August, Ola Electric sold 17,389 units and maintained its pole position for 12 consecutive months. TVS came second with 14,584 units, followed by Ather with 6,835 units (see box). The founder is understandably charged up at the performance. “Layer by layer, step by step, we proved everybody wrong,” says Aggarwal, who is in the midst of transforming Ola from a single brand to a group that has four pillars.

Taking bold bets

He explains the new, evolving business structure. “Ola is a group of four companies,” says Aggarwal. The first is the ride-hailing business, which forms the core. Then comes the electric venture of manufacturing EVs—two-wheelers, three-wheelers and cars. The third is the cell business. “We are India’s largest lithium manufacturing and technology company,” he claims. Ola Electric, he lets on, is the only Indian automotive company selected by the government under its ₹80,000-crore cell PLI (performance linked incentive) scheme. With an initial capacity of 5 GWh, Ola Gigafactory will begin operations by early next year, and will gradually expand in phases to 100 GWh.Ola’s fourth vertical is an artificial intelligence (AI) and silicon division. “It is called ‘Krutrim’, which means ‘artificial’ in Sanskrit,” underlines Aggarwal, adding that the company will launch electric bikes next year. “We are also working on electric three-wheelers and cars,” he says. Ola Electric, he points out, is building products that are required for India. “We are also building the technologies for India. Lithium cell, autonomous technology, motor and electronics… all are being produced in-house,” he claims. Ola, he continues, is building an India EV stack which will drive electrification in the country. “We want to take a few bets which are big enough, bold enough, and will be meaningful for the country’s future,” he emphasises. Impact, Aggarwal points out, has to be the key.

The Futurefactory in Tamil Nadu has an installed capacity of 2 million units a year

The Futurefactory in Tamil Nadu has an installed capacity of 2 million units a year

The fast pace of growth, and the impact, indeed have been astonishing. Back in August 2021, when Ola Electric announced its first product, India’s EV penetration in two-wheelers was less than 1 percent. Now, it is 7-8 percent. “In electric scooters, it is almost 20 percent. So, this is how fast we have come in just two years,” he says, adding that Ola’s vision is to make India a global EV hub. But is it possible? Is he not trying too many seemingly impossible things in a short span of time? Aggarwal smiles. “I feel bigger challenges excite me,” he says.

Also read: Ola Electric Wants To Disrupt India's Car Industry. Does It Have What It Takes?

The founder gets an adrenalin rush by taking up impossible targets. But is he not compressing time and running too fast? Aggarwal defends his pace. “People ask me ‘Why am I in such a tearing hurry?’ And I ask them, ‘Why should I not be?’” he says. The pace, he adds, comes from the purpose of the organisation. “Our purpose as a company is to contribute to India’s growth story,” he says. “We and our ecosystem are not ahead of everyone in the world. But we can be.” When you are coming from behind, Aggarwal explains the logic of running at a furious pace, you have to be in a hurry. “But the speed can’t be at the cost of compromising quality and ethics.”

Fighting fire with fire

Back in April 2022, the quality came under the lens and scrutiny. The company recalled 1,441 units in the wake of a vehicle reportedly catching fire in Pune on March 26. “As a pre-emptive measure, we will be conducting a detailed diagnostic and health check of the scooters in that specific batch and, therefore, are issuing a voluntary recall of 1,441 vehicles,” Ola Electric said in a statement. A few months later, there were reports of issues with the front suspension, and users reportedly took to social media to vent their displeasure. In March this year, the company offered a front fork replacement upgrade to its users. The same month, Aggarwal broke his silence. “Too much myth building and mudslinging happening to us in the last few days,” he tweeted on March 17. “Today, we are publishing a technical blog to share our engineering facts, and break the fake and agenda-driven narrative.”The blog maintained that the company never compromised on quality. “The myth of hardly any testing having been done, being a European product, brought to market quickly, etc. is all false and spread with a deeply malicious intent,” the blog underlined, and showcased extensive steps taken by the company to ensure quality and safety. Regarding the issue of front fork, it noted that there had been 218 failures out of over 2 lakh vehicles on the road. Out of these, the blog points out, 184 are accident cases, and 34 are inconclusive or not accident linked. “Thirty-four out of 200,000 is 0.015 percent and 34 in 700 million km is 1 in 20 million km,” it highlighted. “That number is low enough by any automotive standard to not address. But we decided to address it head-on,” the company maintained, adding that the first inconclusive case was spotted in May 2022, the front fork was reengineered by August, it completed the tooling, testing and validation process by December, and was in production by January 2023. “This pace of engineering is much faster than the conventional automotive world,” it maintained.

Back in Bengaluru, during an exclusive interaction with Forbes India, Aggarwal revisits the fire incident and quality issues. “There was only one fire incident,” he says, adding that a bunch of OEMs (original equipment makers) and companies have had more than this. “We have the best quality test parameters and best processes,” he adds. But what about a barrage of brickbats on social media around service and quality issues?

Aggarwal speaks his mind. “There have been instances where people are waiting for a slip-up from us,” he says. “They hope Ola will goof up so that they can say, ‘We already said this’.” There were rumours, he points out, around Ola importing Chinese goods. “We built such a big factory, and invited all to see… but they vehemently believed the rumour,” he rues. “There has been a lot of noise, but I take it in my stride.” But does it feel unnerving to be constantly under scrutiny? Aggarwal smiles. “It’s okay,” he says. “If you are trying to change the status quo and if you are crafting a path of your own at a scale, people will question you,” he reckons, adding that one has to learn to live in a big boys’ world. “It’s a big boys’ game. If you’re playing with the big boys, you have to be like a big boy.”

Firm backing

Meanwhile, the big backers of Ola are steadfast in their backing of the maverick founder, his vision and the company culture. “Bhavish is not a tech founder. He is a digital industrialist,” reckons Avnish Bajaj, founder and managing director of Matrix Partners. The founder, he argues, must be looked at from the lens of a digital industrialist, and one should be fair in judging him. There are many digital industrialists, he avers, who get away with anything. “Nobody questions their lala culture and questionable management style,” he says, adding that Ola has a hard-charging professional culture. Bhavish, he lets on, is special, and most of the people don’t celebrate the kind of gumption the entrepreneur has exhibited. “Nobody ever gave him a chance. People have written him off so many times. But here he is,” says Bajaj. “He is not misunderstood. I think he is not appreciated enough,” he reckons, putting Aggarwal in the club of Steve Jobs and Elon Musk.Bajaj reckons that one must not have an agenda while judging Aggarwal. As far as the fire incident goes, he underlines, there have been numerous instances of vehicles of well-known auto brands like Tesla and others catching fire. When it comes to Aggarwal, he maintains, the narrative changes. “If it’s not fire, then it’s the organisation. If not the organisation, then some other thing. The guy is always put in the dock,” he says. “It’s not fair.”

Auto experts, meanwhile, reckon that Ola Electric has done a fair job on safety issues post the fire incident and recall. “Yes, there were initial hiccups, but they quickly streamlined and are back on track,” says Amit Kaushik, managing director at Urban Science India. Ola, adds the auto analyst at the Detroit-based global consulting firm, has been striking sustainable growth and has been able to maintain the volumes even after a cut in subsidy. “It shows the product’s acceptability and demand in the market,” he says, adding that legacy ICE (internal combustion engine) players who undermined the strong wave of EVs in the two-wheeler space may face the heat over the next few quarters. “They are chasing a huge India opportunity,” he says.

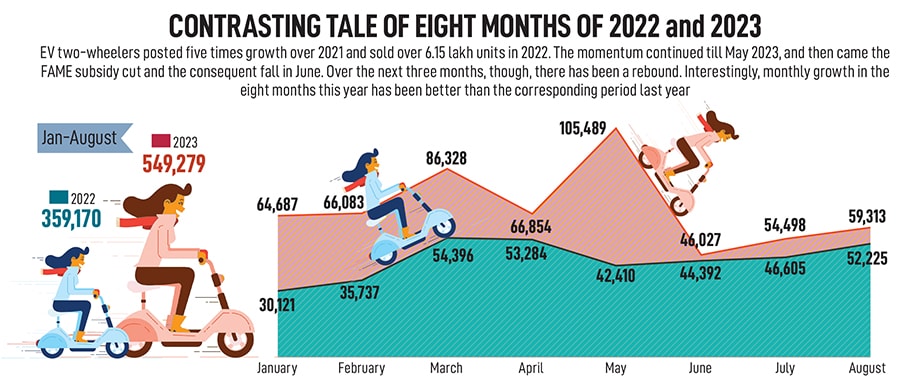

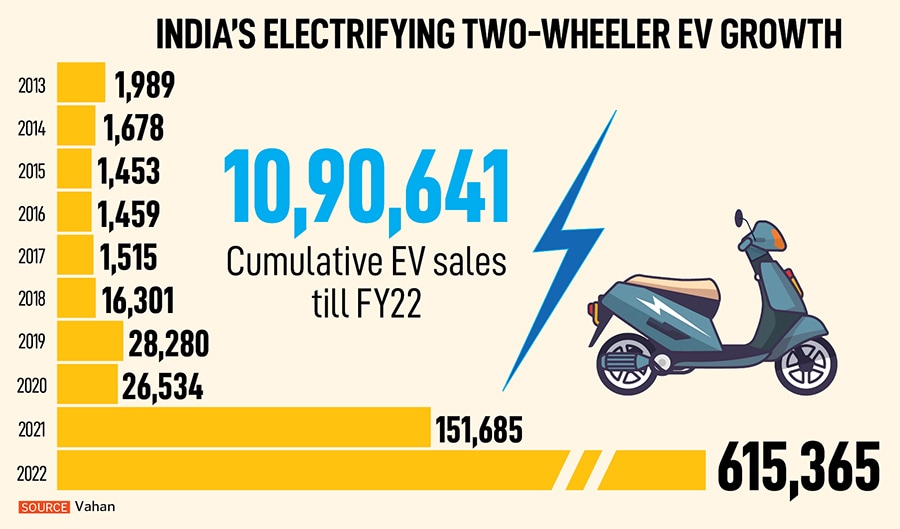

The India EV opportunity indeed looks massive. Look at the numbers. From 1,989 units sold in 2013, the numbers increased to 16,301 in 2018. Though over the next two years there was a sedate growth—28,280 and 26,534 in 2019 and 2020, respectively—it leapfrogged to over 1.51 lakh units in 2021, and then close to a five-fold jump to over 6.15 lakh last year. In terms of percentage, the share of electric two-wheelers in overall vehicle sales is expected to bounce from 4.5 percent in 2022 to over 30 percent by 2030. “I see Ola as a strong player and expect it to keep its growth trajectory intact,” says Kaushik. The challenge, though, for the brand would be to stay away from the temptation of playing price warrior. “Indians don’t want to buy cheap. Ola must not play the price game,” he suggests.

Taking on competitors

Aggarwal, for his part, maintains that money has never been the trump card for the founder. He takes us back to 2013, the year Uber entered India. “When Uber came, they came all guns blazing, and were arrogant,” says Aggarwal, adding that some western companies feel that they only know and understand everything. When the American giant rolled out operations, Ola had around ₹2-3 crore in the bank. “I told my team that the Americans will come, and carpet bomb. But we will be the guerrillas on the streets,” he says. “The inspiration was to fight like Shivaji,” he adds. Had the fight, he underlines, been only about money, then Ola could have never won because Uber had loads of money. “We built a local business model, local products, local technology and emerged the biggest (player),” he says. In FY22, Uber India posted an operating revenue of ₹397 crore and had a loss of ₹216 crore. The equivalent numbers for Ola were ₹1,970.42 crore and ₹1,522.33 crore, respectively.Also read: Innovations will make EVs cheaper than ICE Vehicles: Kunal Khattar of AdvantEdge Founders

The challenge for Ola Electric, though, would be different from Ola cabs. Cabs were confined to services, and Electric has to take care of product as well as service. “Ola Electric needs to make a transition from being ‘the fastest one’ to being the ‘only one’, taking care of customer service and needs,” reckons brand strategist Harish Bijoor. Aggarwal, he points out, has been the poster boy of mobility service and now mobility product. “Though he made a bold move by entering into the electric two-wheeler segment, he was a bit fast in doing so,” says Bijoor, who runs an eponymous brand consulting firm. The problem in being first, he underlines, is that it’s rare when the first mover wins the game in such spaces. The first guy will make mistakes, and the ones who follow will learn from such mistakes. “Bhavish will have to be the ‘one and only’ to cover the grounds on all aspects: Quality, service, branding, customer satisfaction,” he says.

Can Aggarwal step up the game on all fronts? Can he keep his lead intact and ward off threats from established players like TVS, which is breathing down its neck and is second in the EV pecking order? Does he have the deep and wide financial bandwidth to make large investments in EV infrastructure and battery manufacturing? Does he have the patience to play the long game?

Industry observers reckon Aggarwal doesn’t need to worry as far as funding is concerned. “They are fully loaded,” says Jai Vardhan, co-founder at Entrackr. Ola Electric, he points out, is likely to raise $140 million in a new round of funding led by Singapore’s investment firm Temasek, which is already an investor in the EV firm. “They are also preparing for an IPO next year,” says Vardhan, who has been tracking digital entrepreneurs for over a decade. Ola’s opportunity, he maintains, is its biggest challenge. The problem with furious pace is that it always keeps you on the edge. “There is no room for errors,” he says.

A sea of scooters ready for dispatch from Ola Futurefactory in Tamil Nadu

A sea of scooters ready for dispatch from Ola Futurefactory in Tamil Nadu

Dreaming big

Aggarwal, for his part, talks about learning. The biggest, he underlines, came from food delivery and the used-car retail business which had to be closed. “We shut it dispassionately as we were becoming a ‘me-too’ business,” he says. Ola, he adds, does well when it builds technology-oriented large-scale businesses. “That’s our DNA,” he says. When the company, he points out, ended up doing something just because others were doing it, it didn’t make sense.

So, over two years into the electric journey, what makes sense for the founder? “Dream big,” comes a swift reply. Though he declines to put a date on the IPO, he reckons that it would be sooner than later. “And would he hit the public markets after posting profit?” Aggarwal smiles, and declines to comment. “We will ensure that the public market investor makes a lot of money with us over the years,” he says. “Okay. So, would it be two IPOs—Ola Electric and Ola—or just Electric?” “Both,” he reveals his plans. “The dream is to list both of them.” “Really? Possible?” I tried to provoke the man who gets stirred by the realms of impossibility. “If you are going to dream, make it an impossible one. And then make it happen,” he signs off.