Daryaganj Vs Moti Mahal: Amit Bagga's unique journey to redemption

A failed restaurateur was hunting for his moment of redemption, and a doting grandson was yearning to pay rich tribute to his grandfather. The result is Daryaganj, a north Indian cuisine brand, which is in the midst of a bone-rattling legal fight with Moti Mahal

Amit Bagga,Co Founder & CEO, Daryaganj Restaurant

Amit Bagga,Co Founder & CEO, Daryaganj Restaurant

2019, New Delhi. “So, this will be yet another butter chicken brand,” mocked a veteran analyst when he got to know that restaurateur Amit Bagga had teamed up with Raghav Jaggi to start Daryaganj, a north Indian cuisine brand (which has now dragged competitors Moti Mahal to the Delhi High Court over alleged defamatory remarks). “Every non-vegetarian outlet in Delhi serves butter chicken, and everybody has dal makhani. So, how will you guys be different?” wondered a food critic, who was amused with the move to start a new brand in the heart of the butter chicken capital of India. The fact that Jaggi happened to be the grandson of Kundan Lal Jaggi, who along with his partners, invented butter chicken and dal makhani in the 40s when they opened the first outlet in Old Delhi after relocating from Peshawar, didn’t mean much to the industry observers.

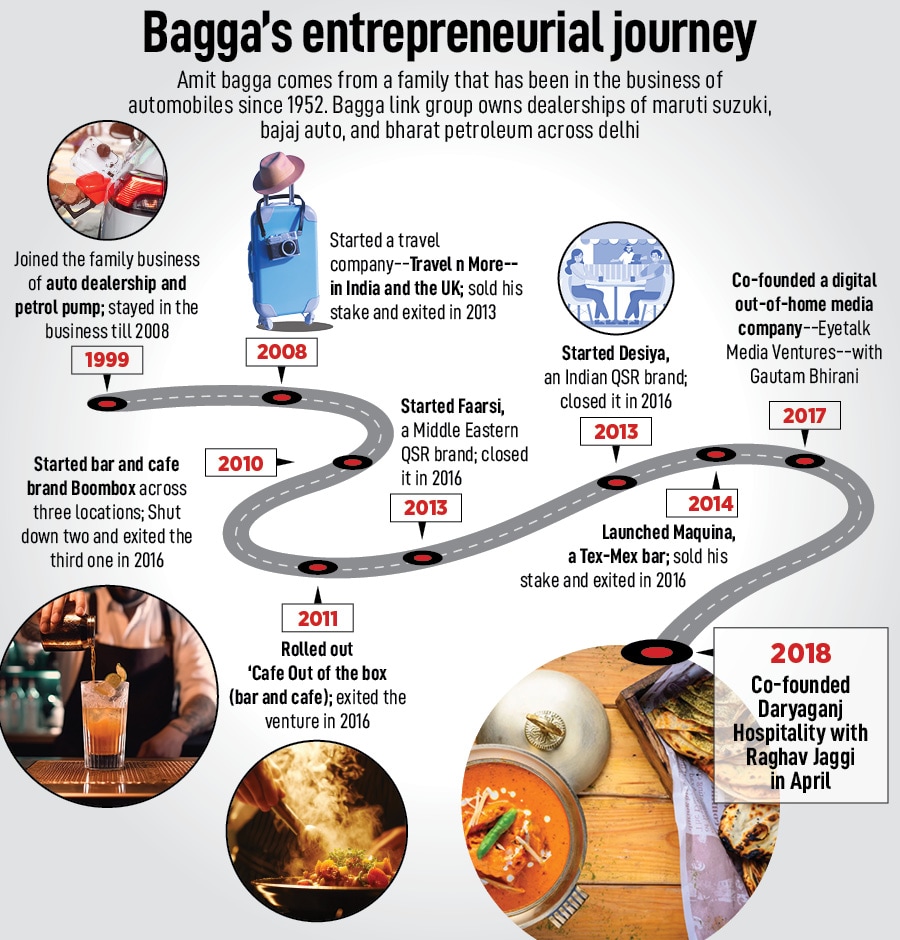

What, however, caught ample attention was the disastrous track record of Bagga, who was ‘certified’ a failed restaurateur by 2018. “After a string of back-to-back failures, everybody had written me off,” recalls Bagga, whose grandfather migrated from Lahore to Karol Bagh in Delhi after the partition in 1947. “He started from scratch and, in the 50s, ventured into the business of automobiles,” recalls Bagga, who joined the flourishing family business of automobiles and petrol pumps in 1999, and gradually learned and imbibed the art of being perpetually obsessed with customer service and satisfaction. “The family business taught me the futility of chasing money and the magic of chasing customer happiness,” he recalls.

Ironically, the family business also taught him self-discovery. It took Bagga close to a decade to realise that he couldn’t continue with a life where his heart and mind were perpetually in conflict. He always aspired to carve an independent identity, and, in 2008, took the entrepreneurial plunge by starting a travel company. Two years later, came another realisation: His mind and heart were still at loggerheads.

“I was a foodie and always wanted to start a food business,” says Bagga, who eventually yielded to his passion and started a bar and café brand Boombox in 2010. Over the next few years, the business boomed, Bagga rolled out a slew of food brands, and warmly embraced and entertained an illusionary thought that he might be the one blessed with a Midas touch. Every bar started churning money, and profit. “There was heady success and fame,” he recounts. “Everything seemed magical,” he adds.

To understand the bitter fight, one must go back to 1947 when Moti Mahal was founded by Kundan Lal Jaggi, Kundan Lal Gujaral, and a third partner. Before Partition, Jaggi and Gujaral worked at a restaurant in Peshawar, which was owned by Mokha Singh. Both came to India as Partition refugees, and started Moti Mahal at Daryaganj in 1947.

To understand the bitter fight, one must go back to 1947 when Moti Mahal was founded by Kundan Lal Jaggi, Kundan Lal Gujaral, and a third partner. Before Partition, Jaggi and Gujaral worked at a restaurant in Peshawar, which was owned by Mokha Singh. Both came to India as Partition refugees, and started Moti Mahal at Daryaganj in 1947.