Euphoria after an Olympic medal: Can it get overwhelming for athletes?

Former Olympic winners on whether incessant number of felicitation functions are distractions, the challenges of getting back on track once the attention fades away, and what India needs to do to ensure more podium finishes at the Games

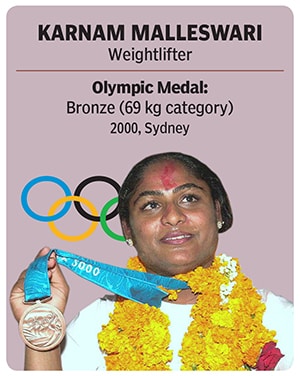

“I was invited for felicitations at a few events, but it was not so loud or glaring as it is now. There was not too much of cash or prize money. We did not even get advertisements… there were no agencies handling our work and no brands chasing us either,” says weightlifter Karnam Malleswari, the first Indian woman to win an Olympic medal, at the 2000 Games in Sydney; Image: KK / PB/ Reuters

“I was invited for felicitations at a few events, but it was not so loud or glaring as it is now. There was not too much of cash or prize money. We did not even get advertisements… there were no agencies handling our work and no brands chasing us either,” says weightlifter Karnam Malleswari, the first Indian woman to win an Olympic medal, at the 2000 Games in Sydney; Image: KK / PB/ Reuters

As she stood on the podium after becoming the first Indian woman to win an Olympic medal, Karnam Malleswari carried with her a tinge of disappointment. The weightlifter aspired for gold, but had to settle for bronze in the 69 kg category “because of a miscalculation by the coaches” at the 2000 Games in Sydney. She realised she had scripted history only later.

At her event, she recalls, the media was conspicuous by its absence. They came only after her medal was confirmed. “They were at the hockey match that day… it is still an entertaining sport (compared to weightlifting). Back then, people were not even aware that weightlifting was an Olympic sport. It was cricket culture that was prevalent then… everyone knew cricketers,” says Malleswari, 46, the sole medal winner for India at the 2000 Olympics.

The mindset in those days, she adds, was such that participating in the Olympics was in itself a big achievement. “One didn’t even think of winning a medal. Nobody had even imagined that I would win one.”

However, after former prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee called Malleswari “Bharat ki beti (daughter of India)”, and news of her victory brought with it a flurry of congratulatory messages, she realised the enormity of her achievement. The slight dejection slowly made way for happiness. Though she got a warm welcome on her return from Sydney, it was not close to the fanfare that we see today.

“I was invited for felicitations at a few events, but it was not so loud or glaring as it is now. There was not too much of cash or prize money. We did not even get advertisements… there were no agencies handling our work and no brands chasing us either,” recalls Malleswari. “The central government gave me Rs 6 lakh and a few States honoured me. Apart from that, neither did anyone call me, nor did I go to meet anyone. Today’s athletes meet film stars and all politicians want to be seen with them. I did not even have a manager… if someone called, I went.”

“I was invited for felicitations at a few events, but it was not so loud or glaring as it is now. There was not too much of cash or prize money. We did not even get advertisements… there were no agencies handling our work and no brands chasing us either,” recalls Malleswari. “The central government gave me Rs 6 lakh and a few States honoured me. Apart from that, neither did anyone call me, nor did I go to meet anyone. Today’s athletes meet film stars and all politicians want to be seen with them. I did not even have a manager… if someone called, I went.”

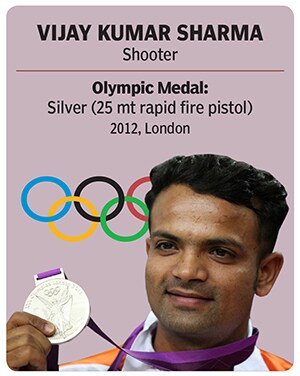

Former Olympic medal winners are of the opinion that such events celebrate a unique milestone that can be achieved only once in four years. Vijay Kumar Sharma, who won a silver in the 25 metre rapid fire pistol event at the 2012 London Olympics, says every athlete dreams of winning a medal.

Former Olympic medal winners are of the opinion that such events celebrate a unique milestone that can be achieved only once in four years. Vijay Kumar Sharma, who won a silver in the 25 metre rapid fire pistol event at the 2012 London Olympics, says every athlete dreams of winning a medal. But how much of it is too much? Where should one draw the line? In an interview with The Times of India on August 25, Chopra speaks about the toll these events have taken on him. “The attention is indeed important, but there is a Diamond League at the end of the month. I had planned to participate in it, but my training completely stopped once I returned from the Olympic Games because of the incessant number of functions. I also fell sick,” he has been quoted as saying.

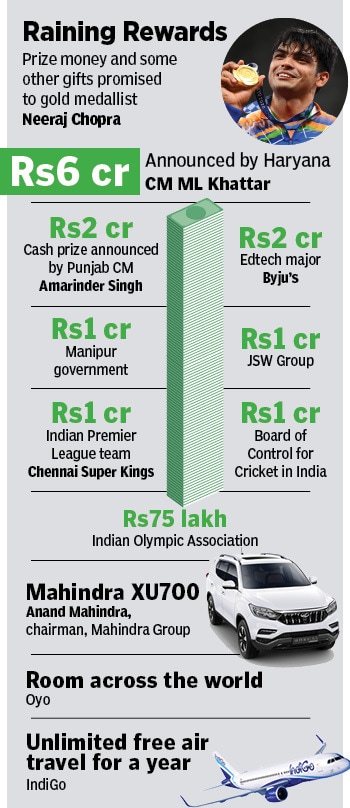

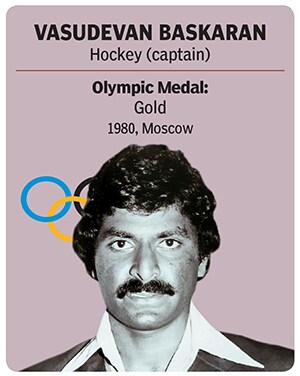

But how much of it is too much? Where should one draw the line? In an interview with The Times of India on August 25, Chopra speaks about the toll these events have taken on him. “The attention is indeed important, but there is a Diamond League at the end of the month. I had planned to participate in it, but my training completely stopped once I returned from the Olympic Games because of the incessant number of functions. I also fell sick,” he has been quoted as saying.  Baskaran, 71, is impressed with 23-year-old Chopra for scoffing at talk about a biopic at this stage of his career although the veteran is certain that the athlete, whose 87.58 metre javelin throw won him a gold, will be a brand favourite. “He is keen to promote himself in a bigger way… his target is 90 metre. The gifts are a form of appreciation from the people. I do not think they are a distraction as long as you keep your head and train well. I personally believe having a car is not a social status. Having a good head is social status,” he says, adding that these winners are not from big cities to get distracted and that they also have good advisors. “There is a lot of money in sport now. When you win, there is more money, but when you lose, there are more brickbats as well.”

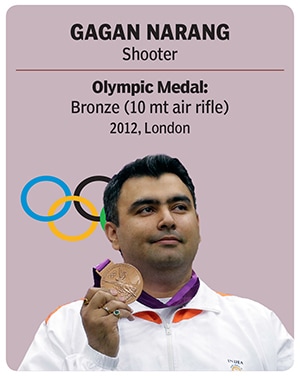

Baskaran, 71, is impressed with 23-year-old Chopra for scoffing at talk about a biopic at this stage of his career although the veteran is certain that the athlete, whose 87.58 metre javelin throw won him a gold, will be a brand favourite. “He is keen to promote himself in a bigger way… his target is 90 metre. The gifts are a form of appreciation from the people. I do not think they are a distraction as long as you keep your head and train well. I personally believe having a car is not a social status. Having a good head is social status,” he says, adding that these winners are not from big cities to get distracted and that they also have good advisors. “There is a lot of money in sport now. When you win, there is more money, but when you lose, there are more brickbats as well.”  Both Malleswari and Baskaran dismiss the possibility of athletes being pushed to anonymity, saying that people remember them even today, decades after the biggest highs of their careers. Narang concedes that every athlete is aware that the attention is part of the success. “It is bound to shift to others when your phase is over,” he says, adding that a medal win opens a whole new world and gives the athlete a window to explore new things. “If they cash in on it, they go farther,” says Narang, who set up the ‘Gun for Glory’ shooting academy before he participated and won the bronze at the 2012 Games.

Both Malleswari and Baskaran dismiss the possibility of athletes being pushed to anonymity, saying that people remember them even today, decades after the biggest highs of their careers. Narang concedes that every athlete is aware that the attention is part of the success. “It is bound to shift to others when your phase is over,” he says, adding that a medal win opens a whole new world and gives the athlete a window to explore new things. “If they cash in on it, they go farther,” says Narang, who set up the ‘Gun for Glory’ shooting academy before he participated and won the bronze at the 2012 Games.  “We are not doing anything for them. We should have proper infrastructure and coaching in rural areas. Till we do that, we will have to struggle for medals. When we do that, India can be No 1 in the world. It can take on China and the US as well. We have that vast a talent pool,” says Malleswari, who runs the Karnam Malleswari Foundation to fulfil the requirements of budding and deserving talent. In June, the recipient of the Arjuna Award, Padma Shri and the Rajiv Gandhi Khel Ratna Award (now renamed Major Dhyan Chand Khel Ratna Award) was appointed as the first vice chancellor of the Delhi Sports University.

“We are not doing anything for them. We should have proper infrastructure and coaching in rural areas. Till we do that, we will have to struggle for medals. When we do that, India can be No 1 in the world. It can take on China and the US as well. We have that vast a talent pool,” says Malleswari, who runs the Karnam Malleswari Foundation to fulfil the requirements of budding and deserving talent. In June, the recipient of the Arjuna Award, Padma Shri and the Rajiv Gandhi Khel Ratna Award (now renamed Major Dhyan Chand Khel Ratna Award) was appointed as the first vice chancellor of the Delhi Sports University.