Vedantu emerges as the frontrunner to acquire Lido Learning which mismanaged its way to bankruptcy

Several factors, including botched investment deals and bad hiring decisions, led to the downfall of the Mumbai-based edtech player

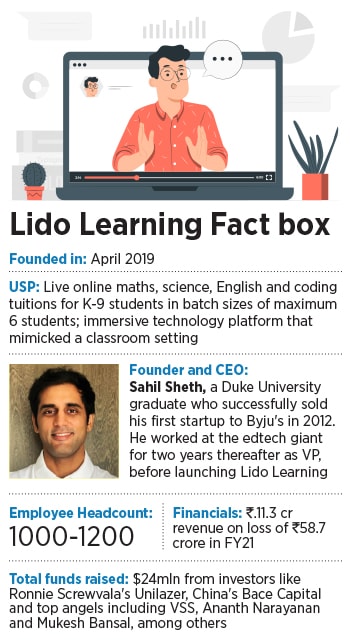

News of Lido shuttering came as a shock to many who believed the startup—which provided live online tuitions to students from classes K-9 in maths, science, English and coding in small groups of six

News of Lido shuttering came as a shock to many who believed the startup—which provided live online tuitions to students from classes K-9 in maths, science, English and coding in small groups of six

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur

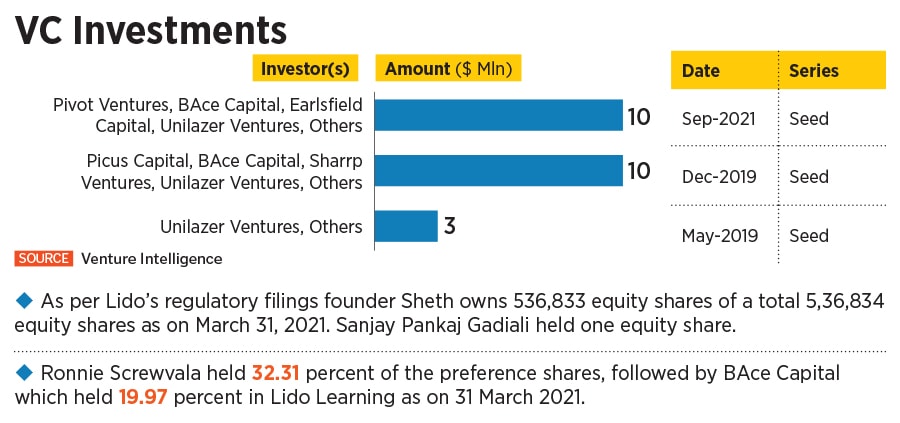

Days after it was reported that edtech startup Lido Learning was closing as it had run out of money, Forbes India has learnt that the Mumbai-based edtech startup is in talks with potential buyers. Byju’s, Vedantu, Unacademy and Reliance are in the fray to buy the three-year-old company, a person familiar with the matter tells Forbes India. Vedantu, he says, is the frontrunner. When reached out for a comment, Vedantu denied any such development.

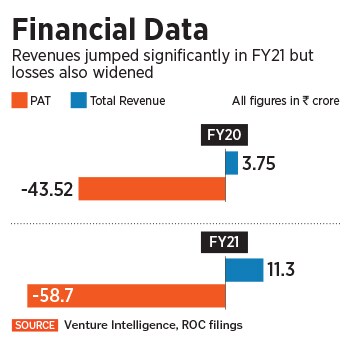

News of Lido shuttering came as a shock to many who believed the startup—which provided live online tuitions to students from classes K-9 in maths, science, English and coding in small groups of six, charging anywhere between Rs25,000 and Rs90,000 after discounts—was in good health.

In an early-February virtual Town Hall, attended by the entire organisation—that is, 1,000-1,200 employees—Sahil Sheth, founder and CEO, announced that the company was closing down as funds had dried up. Employees were told to look for other jobs and that their salaries would be paid within 90 days. “All of us were put on mute so we couldn’t ask any questions. We weren’t expecting this. Nobody knew things were so bad,” says a former employee. Salaries, he says, haven’t been paid since January.

“It was a combination of many things,” says a former senior employee.

“It was a combination of many things,” says a former senior employee.  “For example,” he continues, “these Harvard-Stanford types insisted on marketing through social media instead of using more primitive ways of publicity like

“For example,” he continues, “these Harvard-Stanford types insisted on marketing through social media instead of using more primitive ways of publicity like