- Home

- UpFront

- Take One: Big story of the day

- How India Inc is investing money to turn the nation into an Olympic powerhouse

How India Inc is investing money to turn the nation into an Olympic powerhouse

More and more corporates are stepping up to support sports beyond cricket and fuelling the country's Olympic dreams. It's been a good start, but there is a long way to go

Javelin thrower Neeraj Chopra, who won a gold medal in the Tokyo Olympics, has received support from JSW since his junior days

Javelin thrower Neeraj Chopra, who won a gold medal in the Tokyo Olympics, has received support from JSW since his junior days

Image: Ben Stansall / AFP

Amit Chandra laughs gently when asked if he’s ever been into sports. “If you meet me, you’ll realise I’m the least likely person for it,” says the managing director and India chairperson of Bain Capital Private Equity. “I’ve never played. I have been far from superfit all my life.”

In his day job, Chandra chases staggering digits and builds value through investing. When he steps outside the boardroom, he does more of the same—only, with a separate set of professionals. An inveterate philanthropist, Chandra and his wife donated Rs 27 crore of their personal wealth in FY20, according to the EdelGive Hurun India Philanthropy List 2020. Through the non-profit ATE Chandra Foundation, they have established a network of giving, working primarily with farmers and rural development, and in the area of capacity-building.

There is a notable exception to his portfolio, though. A tranche of Chandra’s philanthropic endeavours is channelled towards the Olympic Gold Quest (OGQ), a not-for-profit that scouts and supports the best prospects among Olympic athletes. According to OGQ’s Annual Performance Report 2019-20, the ATE Chandra Foundation contributed over Rs 25 lakh towards its annual corpus that is spent on coaching, training, buying the best equipment and bringing in cutting-edge sports science to make the athletes Olympics-ready.

“My wife and I have always liked to support causes that are deeply underserved. It used to bother us that we as a nation had a huge aspiration to miraculously do well in sports on the world stage, yet there was very little done in a systematic way to fulfil those aspirations,” says Chandra, who has been supporting athletes through OGQ for nearly 15 years now.

Like Chandra, more and more corporates, either as an institution or in their individual capacity, are stepping up to support sports beyond mere cricket, which is led by the Board of Control for Cricket in India, the richest sporting authority in the country. Not just as a marketing endorsement for medal-winners, but also pumping in funds and bandwidth towards a holistic development of athletes before they make it to the podium.

Consider that, in 2012, leading conglomerate JSW set up a new vertical, JSW Sports, with former tennis player Mustafa Ghouse as its CEO. “We started this after the London Olympics, then the best medal show for India, with an eye towards improving the tally, and to provide the junior athletes with the best-in-class infrastructure and training,” says Ghouse.

Since then, JSW Sports has straddled for-profit and non-profit ventures through owning a bouquet of sports franchises on one hand, and supporting Olympic athletes in five sports—athletics, boxing, wrestling, judo and swimming—through a gamut of services, including building infrastructure, training support, international exposure etc, on the other. Tokyo gold-medallist Neeraj Chopra has been supported by JSW since his junior days, while bronze-winning grappler Bajrang Punia has received its patronage since he was an understudy of 2012 medallist Yogeshwar Dutt.

Like JSW, the Edelweiss Group has been throwing its weight behind Mirabai Chanu much before she became a household name by bringing India’s first Olympic silver in weightlifting; as part of its women empowerment initiative, the group offered Chanu, and five other women athletes, life and health insurance covers and an investible corpus that would ensure them long-term financial security. Equestrian finalist Fouaad Mirza made it to his first Olympics with the sponsorship of the Embassy Group, while, in 2019, the Infosys Foundation, the philanthropic arm of IT major Infosys, committed Rs 16 crore to the Prakash Padukone Badminton Academy for five years to scout for the next Saina Nehwals and PV Sindhus. And these are just a few examples.

(Above) The Edelweiss Group has been supporting Mirabai Chanu much before she won India's first Olympic silver in weightlifting; (Below) Wrestling medal winners from the Commonwealth Games in 2014 being felicitated by JSW; the conglomerate had launched a sports vertical in 2012 to provide junior athletes with best-in-class infrastructure and training; Virendra Singh Gosain/Hindustan Times via Getty Images

(Above) The Edelweiss Group has been supporting Mirabai Chanu much before she won India's first Olympic silver in weightlifting; (Below) Wrestling medal winners from the Commonwealth Games in 2014 being felicitated by JSW; the conglomerate had launched a sports vertical in 2012 to provide junior athletes with best-in-class infrastructure and training; Virendra Singh Gosain/Hindustan Times via Getty Images

“The field of sport is akin to a jigsaw puzzle, where many pieces need to come together to produce a long-term successful athlete. The athlete’s success depends not only on his/her talent but also on the support system s/he receives,” says Sudha Murty, chairperson, Infosys Foundation.

It's a start

Viren Rasquinha, a former India hockey captain and the director and CEO of OGQ, confirms the expanding purse of corporate funding for Olympic sports, saying, for OGQ, it has grown at least 300 percent in the last 4-5 years. “And we can double it in the next 4-5 years.” In 2018, when JSW launched the Inspire Institute of Sports (IIS), a state-of-the-art sporting complex and high-performance centre in Karnataka’s Vijayanagar, it had only a few donors; the number has gone up to 15-plus now, with annual CSR contribution reaching over Rs 30 crore.

The GoSports Foundation, another non-profit venture working towards developing India’s Olympic talents, has seen a 20-30 percent year-on-year growth of corporate funding after the 2016 Rio Olympics, a far cry from its early years when funding came in mostly from family and friends, and in parcels as small as Rs 5,000-10,000. “A key turning period for corporate involvement in sports was the enactment of the CSR mandate in the Companies Act 2013,” says Deepthi Bopaiah, chief executive officer of GoSports. “Some of the activities under the CSR policy included training to promote rural sports, nationally recognised sports, and Paralympic and Olympic sports.”

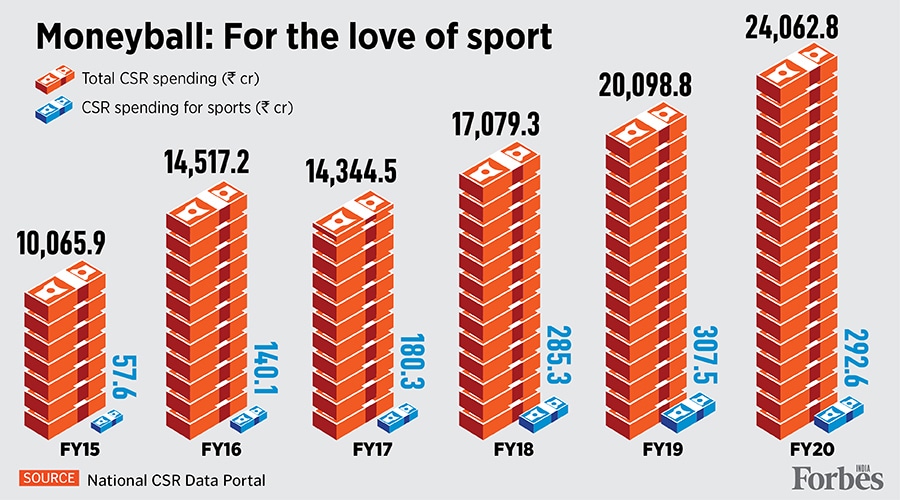

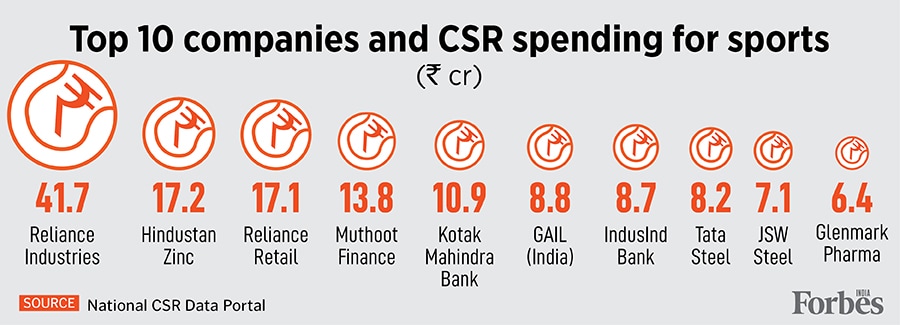

CSR accounts for 70-80 percent of the funding for GoSports, around 65 percent for OGQ, and remains one of the principal modes for the corporate sector’s investment in sports. According to the ministry of corporate affairs’ database, CSR funding for sports has risen from Rs 57.61 crore in FY15 to Rs 292.59 crore in FY20, despite a marginal fall from Rs 307.48 crore in FY19. Reliance Industries [owner of Network 18, the publisher of Forbes India], which has launched multifarious sporting initiatives like the Young Champs and the Junior NBA programmes through its philanthropic wing, the Reliance Foundation, has been the highest spendee in the last recorded fiscal, channelling Rs 41.65 crore of its total Rs 908.71 crore CSR expenditure towards the promotion of sport.

But a closer look at the numbers will also reflect the wide gulf between total CSR spending and that directed at sports. FY20’s Rs 292.59 crore is merely a speck in a cumulative Rs 24,062 crore expended on social causes—in the same year, Rs 9,386.6 crore has been spent on education, differently-abled and livelihood, Rs 6,435.1 crore on health, eradicating hunger, poverty, safe drinking water, sanitation, etc, while rural development has drawn close to Rs 2,252 crore.

“In sports, you are always competing with causes far more rational and practical, like health, welfare, women’s education, sanitation and, in the last one and a half years, Covid,” says Rasquinha of OGQ. “For every big company that we go to requesting for CSR support, there are 50 proposals on their table. The choice for the corporate would be: Do you give money to construct 20 toilets, or send 20 girls to school, or send Olympic hopefuls abroad for training for a couple of months?”

Nation-building through sports

With so many pulls at work, why would a corporate pick the less-tangible (compared to, say, primary education), and less-glamorous (compared to cricket) Olympic discipline as a cause to support? To leverage the power of sport as a change agent and catalyse nation-building. Says Chandra of Bain, “If you are trying to address issues like gender inequalities, the government and foundations working in the area can spend crores to raise awareness. But when you create a few role models, like a Rani Rampal or a Mirabai Chanu, that can have a far more powerful effect than those programmes. That’s what cricket has done, and that’s what Olympic sports can do too.”

Such unstinting support means backing the athletes in the long run, and staying on amidst disappointments—like the lacklustre Rio Games, where India came away with just two medals. Which is why OGQ requests corporate donors to stay on for at least one Olympic cycle of four years and has managed to renew about 80 percent of the total donations on an average over the last four years.

Tata Motors’ association with the Wrestling Federation of India (WFI) is one such tie-up of multiple Olympic cycles (till Paris 2024). “We engaged with a few wrestlers in 2018 and picked up on some of their pain points in areas like international coaching, exposure, sparring with quality partners, injury management etc. That’s when we came up with providing support for two sets of programmes for the elite as well as junior athletes, which was structured by Sporty Solutionz, an advisor to the WFI,” says Girish Wagh, executive director of Tata Motors.

While ‘returns on investment’ is a term that most of these corporates detest and believe is best left behind in the boardroom, Wagh admits the engagement with sports gives the company a good platform to connect with various stakeholders in the business—customers, financiers, insurers, commercial vehicle drivers and channel partners. “We found wrestling as a sport resonates well with the brand attributes that Tata Motors’ commercial vehicles have and helps us in reaching a larger set of audiences,” adds Wagh.

A number of corporate leaders is also opening up their private purse to invest in Olympic sports. While, as a company, the Embassy Group sets aside around Rs 15-18 crore annually for CSR, chairman and managing director Jitu Virwani shells out crores from his own pocket to support the equestrian dreams of Olympian Mirza.

With the Equestrian Federation of India (EFI) an army bastion, and most of its elected office-bearers army personnel, Virwani found it difficult to make inroads as a civilian. “I realised if I relied on the federation, I would be going nowhere. Despite the RBI’s approval, the EFI hasn’t provided with the required NOC to deploy the sponsorship funds. It continues to be a stumbling block in our endeavour to support the sport in India,” says Virwani. “So I started putting in my own money in training riders. From 2014, till now, I have spent about $8-9 million,” he adds. The real estate entrepreneur claims he spent Rs 15 crore on Mirza’s Olympic journey alone. “Equestrian is an expensive sport. The expenses on horses is about €20,000 a month, while we gave Fouaad about €1,000 pocket money per month.” An Embassy REIT will also be channelling Rs 2 crore to the Germany-based International Horse Agency that will train two Indian athletes for the upcoming Asian Games in 2022.

Besides, with the expanse of most Olympic sports going beyond the privileged metro milieu, and athletes coming from varying economic strata and remote corners, it also gives the corporates an opportunity to champion weaker social constituencies. Women, for instance. Rashesh Shah, chairperson of the Edelweiss Group, and his wife Vidya, executive chairperson of the EdelGive Foundation, spend around 10 percent of their CSR budget on sports—a total of Rs 7-8 crore annually divvied up among the OGQ and the Indian Olympic Association (IOA)—with a focus on women.

“When we started supporting OGQ in 2010, non-cricket sports received very little support. And there was even less for women athletes. We decided our support would be only towards women athletes and we continue to do that till this day,” says Vidya. “We’ve supported boxer Mary Kom way back in 2010, two years before she won her Olympic bronze in London, and also other athletes like archer Deepika Kumari, shuttler PV Sindhu among others, for a very long time.”

IndusInd Bank, on the other hand, wanted to change the narrative around para-athletes, from a mere social or CSR target to creating a pure sporting legacy and encouraging inclusivity. In 2016, it created IndusInd For Sports, a non-banking sports vertical, to profess and practise a sports philosophy that was sustainable in the long term for its employees, customers and the community. With about 12-15 percent of its CSR budget directed towards sports, the bank tied up with the para-champions programme of the GoSports Foundation, also supported by Sony Pictures Networks India and AT&T, and helped scale it. “At Rio, 11 of the 19 athletes were funded through this programme, while 21 of the 54 athletes who qualified for Tokyo were part of this programme. Imagine the change,” says Sanjeev Anand, head of corporate banking, himself once a national-level squash player and a keen sportsperson. “It’s a great thing that this counts as a CSR activity. But if it wasn’t, we would still have done it.”

Says Shah of Edelweiss: “At Edelweiss, we have always nurtured a philanthropic culture of investing in society. At our foundation, we don’t say ‘giving back’, because that implies you have taken something that you are giving back. We call it investing back. Like we invest in various companies and businesses, we also need to invest in the country and its social structure.”

Well-begun is only half-done

While the role of the corporates in promoting Olympic sports has gained enough steam and visibility, especially after India’s best show at the Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics this year, the sector doesn’t operate in a vacuum, but in tandem with the government, the biggest stakeholder for sports in the country, as well as the respective sporting federations. That the lion’s share of the funding for sports comes from the government is evident from its Rs 2,596 crore allocation in the Union Budget of 2021, despite an 8 percent dip from the previous year. That’s a long way off from the under-Rs 300 crore CSR expenditure for sports in FY20.

“When I look at the entire CSR space, you have some Rs 50,000 crore available from 2013-2020, and out of that, less than 2 percent comes to sports. Hence, there’s a long way to go. But the fact that even then we have the results, it’s because the government and the TOPS (Target Olympic Podium Scheme) have played a critical role,” says Bopaiah of GoSports. “The government of India doesn’t get enough credit I feel, with the amount of money it spends.”

Amrit Mathur, a senior sports administrator and an advisor to the ministry of sports in 2014 who formulated TOPS that was launched for elite athletes, says that as much as corporate India remains a key stakeholder in the promotion of sports, the government will be the primary driver in a country as large as India. “We need huge money in terms of training, infrastructure, we need huge money to go to the grassroots. No one can do better than the government on that front. Corporate India has just about gotten started to get involved, and will need to play a much bigger role,” he says.

“Also, there must be transparency and disclosure about support/investment for promoting businesses and brands, and no-strings-attached support for sport. Signing athletes for endorsements, sponsorships is a marketing move and, while perfectly legitimate, should not be confused with contribution to nation building,” Mathur adds.

What Mathur wants India Inc to do is go deeper into the grassroots, and not just focus on a section of the Olympic contingent, or just build a few stadiums. The government is the lead player, but corporates will have to play a much larger role than what they do now to fill in where the government can’t.

“Money isn’t actually a problem in Indian sports. The government has enough. The issue is expertise and professional handling, handholding an athlete 24x7, to give him the last-mile competitive advantage. These are the areas where the government isn’t very competent; this is something only a private player can bring in for the athlete. It has been happening and organisations like JSW do good work. Its training centre at Vijayanagar is fantastic; it is an example of creating infrastructure and filling a gap which the government is unable to do. But if I ask you to name 10 private players who are doing enough for Olympic sports, you will struggle,” says Mathur. “Which is why, at this moment, I feel corporate India has been claiming a disproportionate amount of credit, like a 12th player in a cricket team wanting to be the captain.”

In a 2016 report published by the KPMG and the CII (Confederation of Indian Industry), titled ‘The Business Of Sports–Playing To Win As The Game Unfurls’, the limited involvement of the private sector was cited as one of the key issues in the sporting landscape. The report recommended incentivisation of the sector as well as non-profits by providing monetary or tax incentives, and promoting the PPP (public-private partnership) model through favourable policies at both the state and the central level. There has been movement on that front with JSW running the Giri Center for Sports in Hisar, Haryana, with SAI (Sports Authority of India), a high-performance swimming programme along with the government of Odisha and moving forward on another SAI centre in the Northeast. “We’ve hosted two senior boxing nationals and one wrestling national competition at the IIS, held two camps for boxing and the National Cricket Academy, and one each for judo, wrestling, athletics and shooting. We are also a Khelo India accredited centre,” says Ghouse of JSW.

“The biggest difference since the Rio Olympics in 2016,” says Rasquinha of OGQ, “is that all stakeholders are working together. For example, for Mirabai Chanu, the OGQ has worked closely with the weightlifting federation and TOPS for the last five years to ensure all the gaps in the training were looked after. We’ve ensured transparency of funding, eliminated overlaps, and shared research and data as much as possible.”

(Above) Sport legends and board members of the Olympic Gold Quest--billiards world champion Geet Sethi, All-England-winning shuttler Prakash Padukone and grandmaster Viswanathan Anand (extreme right)--with boxing champion Sarita Devi; Manjunath Kiran / AFP. (Below) An aerial view of JSW's Inspire Institute of Sport in Karnataka

(Above) Sport legends and board members of the Olympic Gold Quest--billiards world champion Geet Sethi, All-England-winning shuttler Prakash Padukone and grandmaster Viswanathan Anand (extreme right)--with boxing champion Sarita Devi; Manjunath Kiran / AFP. (Below) An aerial view of JSW's Inspire Institute of Sport in Karnataka

Recently, WFI President and MP Brij Bhushan Sharan Singh fired a salvo at private organisations like JSW and OGQ over Vinesh Phogat’s alleged ‘improprieties’ in Tokyo and subsequent suspension. In an interview to The Indian Express, he argued that the federation was in the dark over Phogat’s plans, which were emailed directly to TOPS, and threatened ‘bilkul nahi khelne doonga (‘won’t allow players associated with such organisations to play)’. “We don’t need OGQ and JSW,” Singh said in the interview.

Phogat was later let off with a warning, but the flashpoint has opened a conversation on how the government-private collaboration can be made more seamless. Perhaps delineating roles for each stakeholder is a way out. “The sports ministry is the main stakeholder and it will have to get others on board with a clarity about roles to ensure cohesion,” says Mathur.

The private sector is game. “We were a bit surprised with the comments of the WFI chief. We have reached out to him thereafter on multiple occasions. We are working closely with them and will continue to do so,” says Ghouse of JSW.

To borrow a sporting analogy, the journey to the Olympic podium is a marathon, and not a sprint. And the jump in India’s medal count—from two in Rio 2016 to seven in Tokyo 2020, including an individual gold—indicates the stakeholders are on the right track. If the creases are ironed out amicably, India’s dreams of turning into an Olympic powerhouse might not be distant anymore.