How PhysicsWallah solved the profitability equation

In little over three years, Alakh Pandey has cracked the dynamics of running a profitable and thriving edtech venture that has scaled at a furious pace. Can he maintain the high momentum?

Alakh Pandey, Founder, PhysicsWallah Image: Madhu Kapparath

Alakh Pandey, Founder, PhysicsWallah Image: Madhu Kapparath

“Is there any connection between fiction and friction?” For a writer, the obvious answer is: Remove the letter ‘r’ and both words spell the same. But Alakh Pandey, an unconventional physics teacher, has a different take. A good fiction and friction, says the founder and chief executive officer of PhysicsWallah, helps build a beautiful world. Alice in Wonderland is good fiction, and “if you are able to write on a blackboard or notebook, it is friction,” says the first-generation entrepreneur who started PhysicsWallah as a free YouTube channel in 2016.

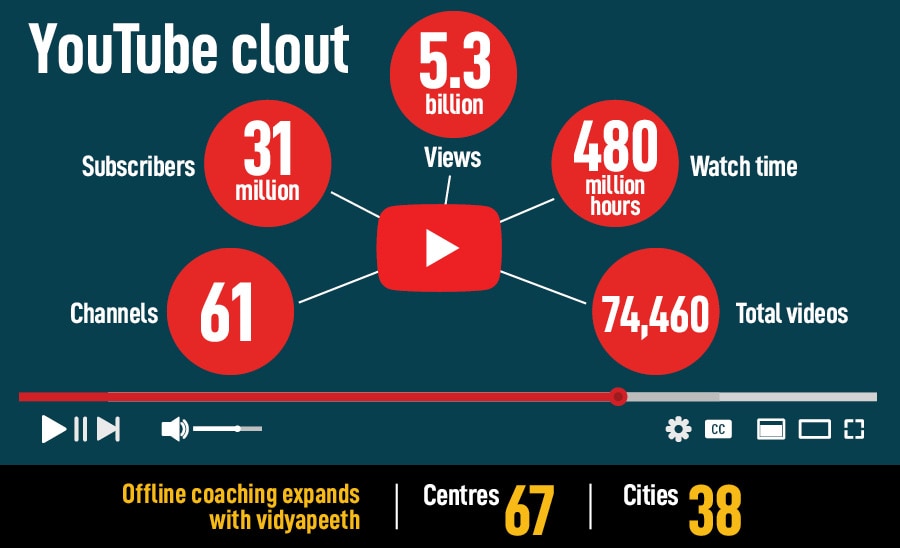

“Thanks to friction, you have been able to drive, travel, walk, or drill a nail into the wall,” he says. “The last time you ironed a shirt…that’s again friction,” the physics guru continues in his trademark way of simplifying things, which has helped him build a cult following on social media: Some 31 million subscribers, 61 YouTube channels, and 5.3 billion views. “The numbers are not fiction,” he grins.

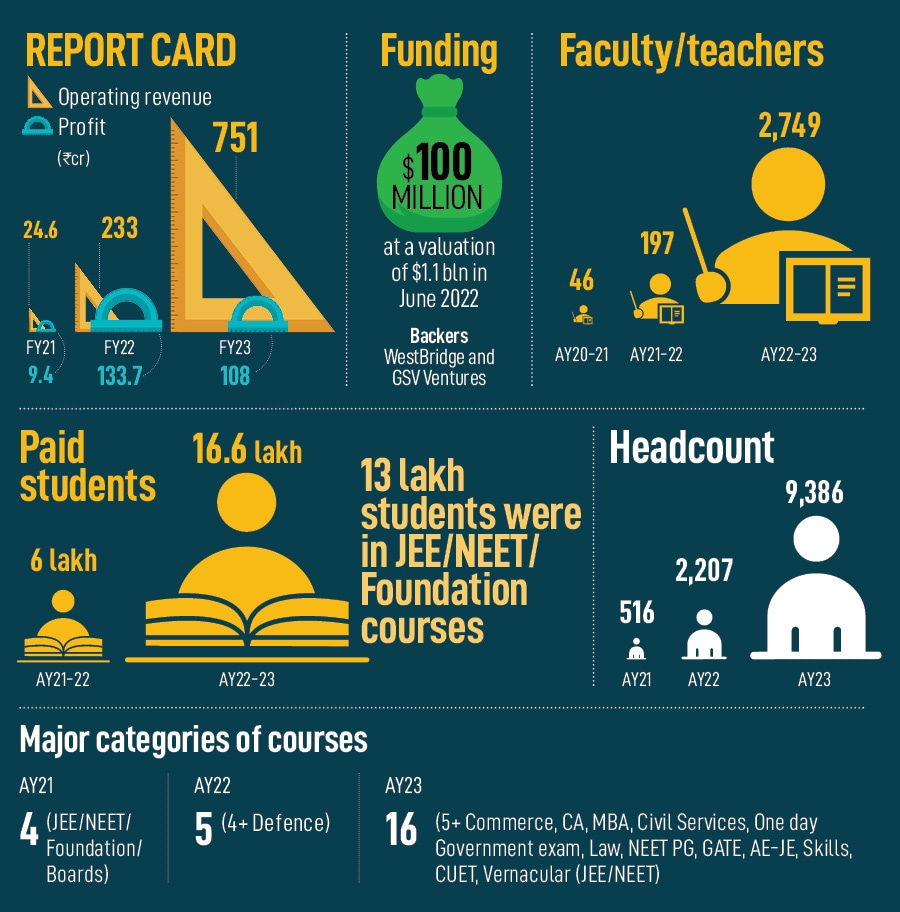

But there seem to be strong fictional elements in Pandey’s entrepreneurial journey. Take, for instance, how he dashed into the unicorn club with his very first fundraise, which gave PhysicsWallah a valuation of $1.1 billion. Then there is the staggering revenue jump in three years: From Rs24.6 crore in FY21 to Rs751 crore in FY23. The jewel on the crown is perhaps three years of profitability since Pandey monetised his venture in 2020—Rs9.4 crore, Rs133.7 crore and Rs108 crore in FY21, FY22 and FY23, respectively. Pandey’s entrepreneurial journey reads like a fairy tale. “It’s velocity,” he says, bursting into a loud guffaw.

He then quickly walks out of his cabin on the eight floor of a 10-storey building in Sector 62 of Noida, Uttar Pradesh. “Sorry bachhhon, disturb toh nahin kiya (Sorry kids, hope I didn’t disturb you),” he apologises. PhysicsWallah has three floors in the building, spread across 67,000 square feet of space. A minute later, the teacher is back.