How Taj Hotels is revamping its age-old business model

Over the last five years Indian Hotels has moved from being largely owner-driven to one that is expanding via management contracts. Add to that newer avenues of income, and there is reason for CEO Puneet Chhatwal to be optimistic

Puneet Chhatwal, CEO IHCL

Image: Amit Verma

Puneet Chhatwal, CEO IHCL

Image: Amit Verma

A short walk from Mumbai’s domestic airport, near the iconic, circular-shaped Sahara Star hotel, construction workers toil busily. A 371-room Ginger hotel–from the Taj stable–is being built for a May 2023 opening. The prime piece of land always belonged to Indian Hotels Company Limited (IHCL), the Taj hotels’ parent company, but for the last 25 years, since the flight kitchen that it previously housed shut down, it has been unutilised.

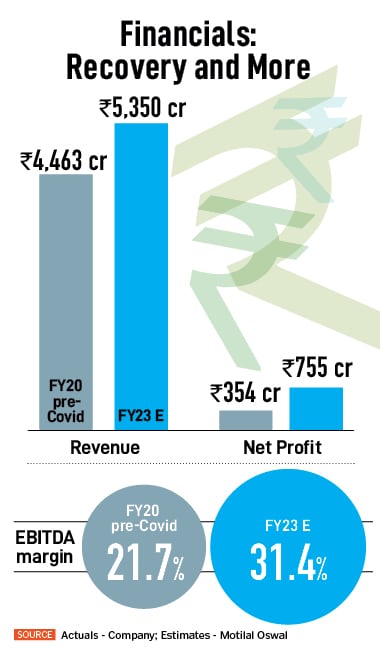

IHCL expects to achieve 55 percent EBITDA margins on the property from the first year of operations itself. The entire exercise is part of what IHCL’s CEO Puneet Chhatwal calls “re-imagining Ginger”, a previously budget, functional hotel chain that is now being given an aspirational makeover, while still keeping costs low. “It’s a lean-luxe hotel. It will afford you a comfortable stay at a compelling price and you still have all the luxuries that you need, but the hotel is built in such a lean fashion that it doesn’t cost much to build,” he says. In fact, so bullish is IHCL on the Ginger brand that the company acquired 100 percent of its parent Roots Corporation in October 2021, up from 60 percent earlier. “It’s a brand to watch,” nods Chhatwal.

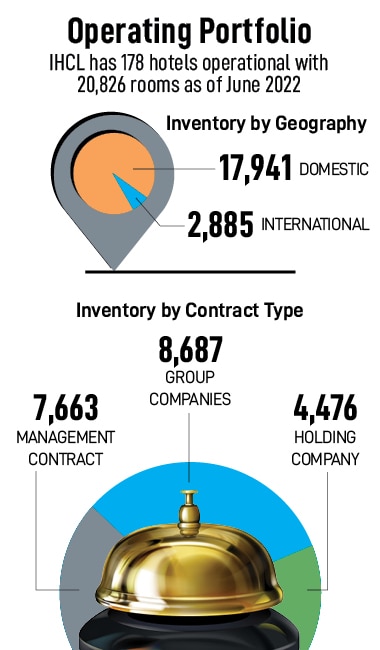

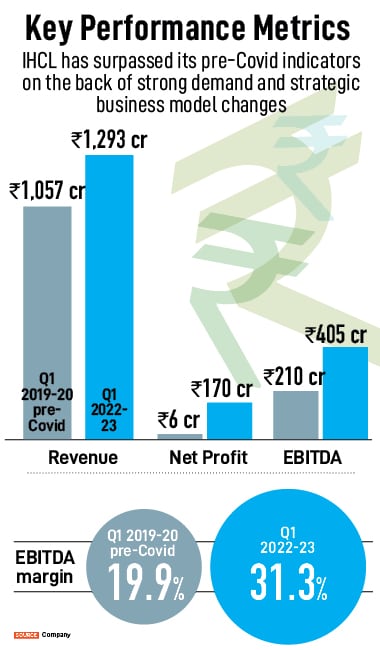

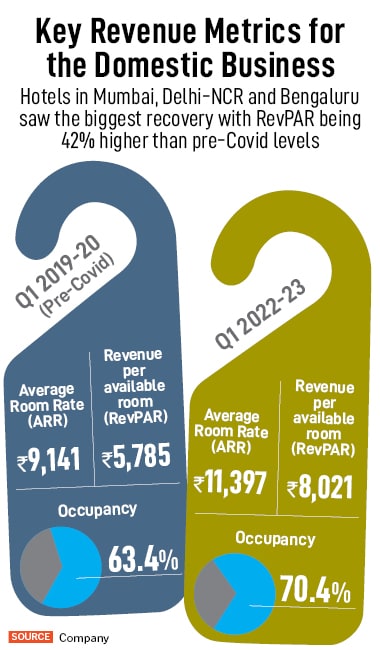

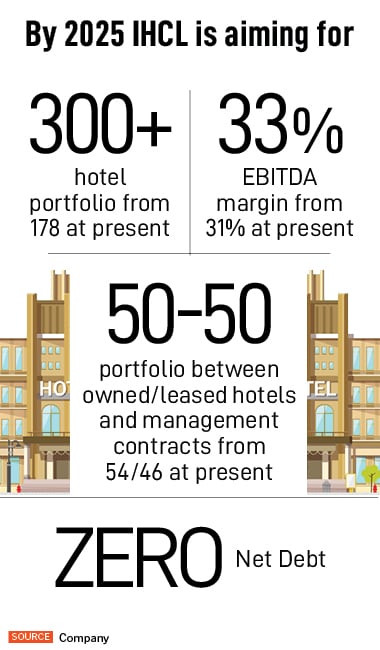

Tall and bespectacled, Chhatwal, who led hotel chains in Europe and America before taking over as IHCL’s CEO in 2017, speaks deliberately, carefully weighing every word. “We want to achieve sustainable, profitable growth in everything that we do,” he says. To that end, Ginger isn’t the only big bet he’s making. Over the last five years he’s steadily moved IHCL away from being a largely owner-driven company to one that is swiftly expanding via management contracts. Today, IHCL has a 54-46 percent balance between owned/leased and managed properties in its portfolio. By 2025 it hopes to achieve a 50-50 percent balance between the two.

Lessons from the pandemic

Lessons from the pandemic Shift in business model

Shift in business model This asset-light strategy might be new for IHCL but it has, in fact, been in vogue globally for the past two decades. Big hotel chains have steadily offloaded their hotel buildings to focus on managing properties for other investors or ensuring that franchisees who own and operate the hotels comply with brand standards on service and staffing. In the US, for example, just five percent of hotels are owned or directly managed by chains, while 53 percent are franchises, up from 47 percent a decade ago, according to hospitality data provider STR.

This asset-light strategy might be new for IHCL but it has, in fact, been in vogue globally for the past two decades. Big hotel chains have steadily offloaded their hotel buildings to focus on managing properties for other investors or ensuring that franchisees who own and operate the hotels comply with brand standards on service and staffing. In the US, for example, just five percent of hotels are owned or directly managed by chains, while 53 percent are franchises, up from 47 percent a decade ago, according to hospitality data provider STR. Similarly, Ama, a homestays business, took off after guests indicated their desire for exclusivity in the depths of the pandemic. The Tata group’s private holiday homes for employees nestled amidst coffee plantations and hill stations were offered to premium customers on a short stay basis. The business has since morphed to include not just Tata properties but also third party-owned properties. “It’s all about the trust. If you are an owner of a villa which costs Rs 5 crore would you give it to the Tatas to manage or would you give it to someone else to manage?” says Giridhar Sanjeevi, chief financial officer, IHCL. The trust factor has led to IHCL signing on 100 properties so far; it plans to take it to 500. “We see very high potential with Ama. The beauty of this model is that it is asset light. We are not investing monies, we just collect a fee.”

Similarly, Ama, a homestays business, took off after guests indicated their desire for exclusivity in the depths of the pandemic. The Tata group’s private holiday homes for employees nestled amidst coffee plantations and hill stations were offered to premium customers on a short stay basis. The business has since morphed to include not just Tata properties but also third party-owned properties. “It’s all about the trust. If you are an owner of a villa which costs Rs 5 crore would you give it to the Tatas to manage or would you give it to someone else to manage?” says Giridhar Sanjeevi, chief financial officer, IHCL. The trust factor has led to IHCL signing on 100 properties so far; it plans to take it to 500. “We see very high potential with Ama. The beauty of this model is that it is asset light. We are not investing monies, we just collect a fee.”