- Home

- UpFront

- Take One: Big story of the day

- India wants to take CoWin global, but it remains disempowering for many back home

India wants to take CoWin global, but it remains disempowering for many back home

The technology platform at the centre of India's Covid-19 vaccination strategy is out of reach for those without digital access or know-how, while vaccine supply constraints and data security issues spark additional concerns

Divya writes about gender, philanthropy, startup and workplace trends, and business from the lens of its impact on people. She is keen to find interesting stories and new ways of telling them. A journalism graduate from Mumbai who was previously with The Economic Times, Divya is also an editor and proof-reader. Outside of work, she likes to travel, read books, drink hot chocolate, and endlessly watch, read and talk about cinema.

- For businesses, sustainability should be a leadership challenge, not a cost problem: Rajeev Peshawaria

- Philanthropy for mental health should focus more on community-led models

- I was never taken seriously as someone who can build a business: Masoom Minawala

- Indian companies should focus on high value manufacturing: Vijay Govindarajan

- Roop Rekha Verma's unwavering fight to uphold constitutional values

Low digital literacy, inadequate last-mile health infrastructure and vaccine supply constraints have resulted in just 6 crore people getting fully vaccinated as of July 4

Low digital literacy, inadequate last-mile health infrastructure and vaccine supply constraints have resulted in just 6 crore people getting fully vaccinated as of July 4

Image: Sanchit Khanna/Hindustan Times via Getty Images

The Jawhar and Mokhada taluks in the Palghar district of Maharashtra are just a three-hour drive from Mumbai, but in terms of human development indices, they are many decades behind. They are home to tribes including the Warli, Katkari, Kokana and Mahadeo Koli, many of who are small farmers, landless labourers or daily wage earners struggling to make a living in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Related stories

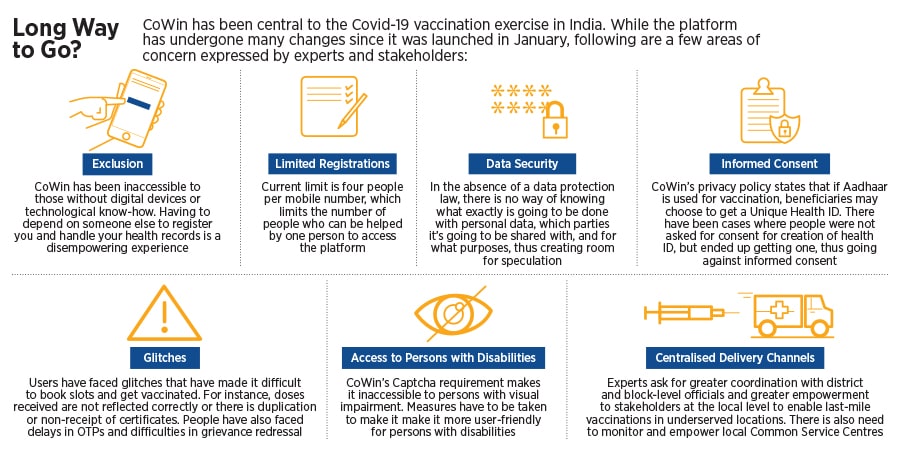

Vaccinating people in these taluks presents a different set of challenges. First is the fear of vaccines, due to low awareness, illiteracy and misinformation. Second, it is nearly impossible to use the digital-centric route through the CoWin platform, which the government calls the “technological backbone” of India's vaccination process.

Many people in Jawhar and Mokhada do not own smartphones; among those who do, some cannot navigate CoWin, while others struggle with patchy internet connectivity, says Sarika Kulkarni, founder of the Raah Foundation, which has been helping with vaccinations in these areas. “Many places do not have basic cell phone reception. Forget 4G, even the 2G network is poor,” she adds.

According to her, many tribals, including 40 to 50 percent of senior citizens, do not even have an ID proof, which is mandatory for vaccine registration. Getting IDs made delays their vaccination by atleast another two to three weeks, she explains, adding that CoWin allows just four registrations per ID card, which limits the ability of people with access to register others.

Kulkarni is working with the district administration officials and ASHA workers to facilitate offline vaccination camps that involve paper-based registrations. The beneficiary data is uploaded to CoWin only when there is network connectivity, and vaccination certificates are distributed later. “If we depend on the internet, we won’t be able to vaccinate even half the people in this area,” she says. “If a digital platform is at the centre of such a crucial process, there are bound to be multiple challenges.”

Need ears on the ground

The harsh realities of the Covid-19 vaccination process— low digital literacy, inadequate last-mile health infrastructure and vaccine supply constraints—have resulted in just 6 crore people getting fully vaccinated as of July 4; this is less than 7 percent of about 94 crore adults.

The government has set an ambitious target to vaccinate the entire adult population by year-end, for which it will need to administer about 188 crore doses. With six months to go, it is now on the 35 crore mark. Between January 16 and June 30, on an average 20 lakh people were vaccinated per day. To reach the annual target, this number has to go up by almost five times. Meanwhile, vaccine shortages and booking slots through CoWin has turned into a scramble.

The Supreme Court (SC) recently said that CoWin creates a digital divide in vaccine access, and that even the digitally literate are finding it difficult to get slots on the platform. “A vaccination policy exclusively relying on a digital portal for vaccinating a significant portion of the population of this country between the ages 18-44 would be unable to meet its target of universal immunisation owing to such a digital divide,” said a special bench, led by Justice DY Chandrachud, in an order released on May 31. “It is the marginalised sections of the society who would bear the brunt of this accessibility barrier.

This could have serious implications on the fundamental right to equality and the right to health of persons within the above age group.” The bench added that the government must have “ears on the ground”.

RS Sharma believes that lack of direct access to CoWin is not a concern, as those who cannot self-register can get it done through health professionals at vaccination site

Image: Madhu Kapparath

It is against the backdrop of these developments that the government is planning to take the CoWin platform to other countries for their vaccination programmes. “When our Prime Minister was reviewing the National Digital Health Mission on May 27, he directed us to open-source the software and platform, and give it as a gift to anybody who wants to use it. So we will give this free-of-cost to any country that wants to take advantage of the platform and modify it [as per their requirements],” says Ram Sevak Sharma, head of the CoWin platform and CEO of the National Health Authority (NHA). “Various countries have registered for the conclave, which you can count as an interest shown in the platform." As of July 4, close to 50 countries had registered for the conclave, including Iraq, Peru, Mexico, Panama, Vietnam, Canada, Dominican Republic, Uganda and Nigeria.

Addressing the global CoWin conclave on July 5, Prime Minister Narendra Modi said that India had decided right from the beginning to adopt a "completely digital approach" while planning its vaccination strategy. The Indian civilisation considers the whole world as one family, and the pandemic has made many people realise the fundamental truth of this philosophy, he said. "That's why our technology platform for Covid vaccination, CoWin, is being prepared to be made open-source," he said.

Back home, however, most Indians continue to struggle to access and navigate the platform. According to Statista, a data research firm, smartphone penetration rate in India is 41 percent in FY21, and is estimated to cross 51 percent by FY25. The SC, in its order, also pointed to a National Statistics Office Survey of 2018, which said that around 4 percent of rural households and 23 percent of urban households owned a computer, while internet access rate was at 15 percent in rural areas and 42 percent in urban areas during the same period.

Sharma believes that lack of direct access to CoWin is not a concern, as those who cannot self-register can get it done through health professionals at vaccination site. He says that “80 percent of the people in this country get registered through walk-ins, only 20 percent are using the reservation and booking system”. He also says that assisted bookings can be made through call centres and Common Service Centres (CSCs), which are physical units set up to take e-governance services to rural and remote locations.

Aishwarya Narayan, research associate, Dvara Research, says that vaccination data estimates place the number of registrations through such assisted models at a meagre 1.5 percent. “Faced with some evidence on low availability and uptake of CSC services in the context of vaccine registration, it is worth looking into the larger issues that plague their functioning,” she says.

According to Prashanth N Srinivas, assistant director (research) at the Institute of Public Health, Bengaluru, CoWin has not yet been able to fulfil its basic purpose, which is to improve the efficiency of vaccine delivery by making doses accessible at lesser human and manpower cost, compared to traditional inoculation systems. “If I have to depend on someone else to access my rights and entitlement to a technology, that itself is a disempowering experience,” he says.

He gives the example of Chamarajanagar district in Karnataka, where he is based, and where he works with the local Soliga tribe. The rural district has very little private sector penetration and development, and low literacy levels, Srinivas explains. “There are so many settlements where piped water has not yet reached. More than half the population does not have access to proper roads. There is no telephone coverage in many places. So I cannot even imagine CoWin’s role here.” Till June-end, about 3,158 inhabitants of Chamarajnagar, out of 15,568 eligible ones, had received at least one vaccine dose.

Srinivas believes that a CoWin-centric vaccination strategy is unsuitable for such settings. It is the concerted offline effort of local community leaders, health workers, non-profit organisations and district administrations that is driving the inoculation process, he says. “When districts realised that vaccination is the only way out, it also dawned upon them that CoWin will not work. So they tried to figure out ways to personally connect with each person to get them vaccinated.”

The system has self-corrected itself, he explains, with measures that involve generating awareness, putting manpower on the ground, and creating a paper trail to vaccinate people. “So CoWin’s purpose of being a platform that provides sophisticated, real-time data is gone,” says Srinivas, adding that the platform should have factored in the diversity of ideas, people and geographies that interface with its technology. “Now CoWin is like this elephant in the room no one wants to address.”

In Delhi, for instance, the local administration has a “special arrangement authorised by district magistrate” to vaccinate homeless people, many of who do not have any form of ID, says Sunil Kumar Aledia, executive director, Centre for Holistic Development. He is working for the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board (which runs over 209 temporary shelters with close to 4,000 people) where they identify one person in the shelter with an ID. “We create a patch of 100 vulnerable people who could get vaccinated, based on that one person’s ID,” he says.

Apart from the digital divide, many rural vaccination sites are far from villages and people do not have the means to travel. “So they wait for vaccination sites to be set up nearby. In villages, vaccination is not yet a priority, so people won’t do it themselves until we take the vaccine to them,” says Aliva Das, senior manager of non-profit Transform Rural India (TRI), which has close to 2,000 volunteers in Jharkhand and Madhya Pradesh to help people navigate CoWin. One challenge here is that while people do not know how to self-register, they are also skeptical about sharing their ID details with community workers.

Das adds that in the areas where she works, people between 18 and 44 years still had to pre-book slots on CoWin, instead of walk-ins. The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare had initially made online registrations mandatory for this age group, to reduce overcrowding at vaccination centres, but subsequently allowed walk-ins at all centres.

Das believes that the government is not decentralising or opening more centres because of vaccine shortages. She has seen centres that need a minimum of 10 people to start vaccinations and prevent wastage, and if fewer people turned up, they were denied vaccines. “If denied once, people do not return for vaccination, no matter how much you persuade them,” she says. Another reason why vaccines have to be taken to rural people, instead of the other way around, is because many of them cannot afford to spend hours at the centres or make multiple visits, as it might lead to loss of earnings for the day.

Then there are glitches on the CoWin platform. Teekaram Mouhari, one of TRI’s community volunteers from Samnapur block in Kanchanpur village of Madhya Pradesh, got vaccinated on June 1, but his certificate still doesn't reflect on CoWin. “They [officials] are saying it’ll get updated, but it’s already a month so we don’t really know when it’ll get resolved,” Das says.

India’s vaccination policy has seen multiple flip-flops. After launching it on January 16, the government initially aimed to vaccinate 30 crore health care and frontline workers, senior citizens and persons with comorbidities by July, before vaccinating everyone else. On March 1, it opened vaccinations to people above 60 and those over 45 with comorbidities. On May 1, as Covid-19 cases began to surge during the second wave, the government opened vaccinations to all adults, which is close to 70 percent of 136 crore people, and placed greater responsibility with the states. This led to a scramble among states to procure vaccines, which were in limited supply.

This resulted in people desperately trying to book slots on CoWin, which got filled within seconds. “CoWin only shows vaccines available, right? It can’t produce vaccines,” says Sharma. “When vaccinations were opened for 18- to 44-year-olds, a number of vaccines were not available. There was a huge demand and less supply. But now the situation has changed completely. Now you can get slots easily.”

Berty Thomas agrees that while the gap has been bridged to a certain extent in major cities, there continues to be significant disparity in many places. The analyst from Chennai, who is also a programmer, struggled to find a slot when vaccinations were opened to all adults, and decided to gain an upper hand. He wrote a script over CoWin’s public API (application programming interface) to help identify available slots for his age group in his city.

“There is a clear advantage in using the API, rather than going through the whole list of centres on CoWin, which was not user-friendly,” says Thomas. It was not possible to quickly go through the entire list to spot vaccines available for 18+ people because CoWin also shows slots for the 45+ group, or centres with zero slots. “That is a challenge I wanted to solve, so that people can quickly access slots meant for them.”

Thomas decided to run the script on the server that would issue alerts as soon as slots were available. His website under45.in adds people to relevant Telegram groups in their areas. As of July 1, his tool was being used in 675-odd districts across the country and has 41 lakh subscribers. As of July 5, code-sharing service Github showed 2,430 repository results for CoWin slot-booking alert systems in India.

But despite the alerts, it is still difficult to find slots, Thomas says. “For example, until about two weeks ago in Ernakulam, Kerala, we had close to 60,000 to 70,000 people in the Telegram group wanting vaccines, but only 200 or 250 slots opened on a daily basis. Even those 250 slots did not come together, but in batches of 100 or 50, making it more difficult for people to access CoWin and book slots,” he says.

Thomas sees the usefulness of CoWin as a centralised database of information for studying data trends for pandemic management. “We face issues because everyone does not have access to the internet, plus there’s a vaccine shortage,” he says. “So while I understand the need for CoWin, I don’t know how well its current form has been thought through.”

How will all this data be used?

CoWin was created without a 'privacy by design' approach, says Prasanth Sugathan, legal director, Software Freedom Law Center, India (SFLC.in). “SFLC.in had flagged the lack of a specific privacy policy during its launch. It took the NHA almost 5 months to come up with a specific privacy policy.”

There are issues with the privacy policy in its current form too. For instance, under Use of Information is a term that those using Aadhaar may choose to get a Unique Health ID (UHID). However, for generating a UHID you need to be authenticated through any of the means for Aadhar authentication at the time of verification at the vaccination centre.

Sugathan says they know of several instances where “people had not been asked for consent for creation of UHID, but ended up getting one. This does not constitute informed consent,” he says, adding that creation of UHID “under the garb of vaccination process” is not in compliance with the SC decision in KS Puttaswamy vs Union of India (2017) on the Fundamental Right to Privacy.

Tanmay Singh, associate litigation counsel at the Internet Freedom Foundation, says that CoWin is following the Aadhaar playbook. “While people now have a choice to link CoWin with UHID, we have seen in the past how 'voluntary' has become 'mandatory' and people are left with no choice but to comply,” he says, adding that this is likely to become a bigger concern as the UHID gains ground in the wake of the scaling up of the National Digital Health Mission (NDHM). He points to how Digilocker is a partner programme for CoWin. “This is all a data-collection exercise.”

The Personal Data Protection (PDP) Bill, 2019, has still not been passed by Parliament, in the absence of which, there is no clarity on how the government will use the personal data collected via CoWin, says Singh. “This is a cause for concern, because we don’t know what is going to be done with this data, which parties this is going to be shared with, and for what purpose. It creates a lot of room for speculation, which, ideally, should not exist.”

He also says that as per the terms in CoWin’s privacy policy, the obligation to keep your data secure is not upon CoWin, but on you. “This is surprising, because once you have given the data to CoWin, I’m not sure what you can do to keep your own data secure on the platform. So that is certainly a potential problem.”

Sugathan says that as per the privacy policy, users do not really have any control of their data. “They cannot delete their data from the CoWin portal once they are vaccinated. They cannot opt-out from data-sharing with third-parties by the NHA,” he says. According to him, CoWin also needs to be made more accessible to differently-abled people. The Captcha requirement, for instance, makes it difficult for visually challenged people to access the site. “We are still hearing about people facing difficulties with grievance redressal and delays in OTPs. That needs to be fixed as well.”

Sharma, who was one of the main architects of Aadhaar in India as the chief of the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI), sees a life beyond Covid-19 vaccinations for CoWin by deploying it for other vaccinations and immunisation programmes in the future. He says that in five months since its launch in January, CoWin has got about 300 million registrations. “You cannot say that a product has achieved finality in five months. It is obviously a work-in-progress and we will continue to add features as required by the policy or people-centricity of the platform.”

Singh agrees that officials have been consistently improving CoWin, based on feedback, which is why the platform today is not the same as the one that was launched in January. “But when you make a platform of this nature, and more importantly, when you make it the only way to access vaccines, you must get it right the first time. Because if there are issues that lead to even 1 percent of the population getting excluded, that's more than a crore people,” he says. “With the technology solution as it is now, you stand to exclude not just 1 percent, but 20-30 percent of the population, which is a mind-boggling number.”