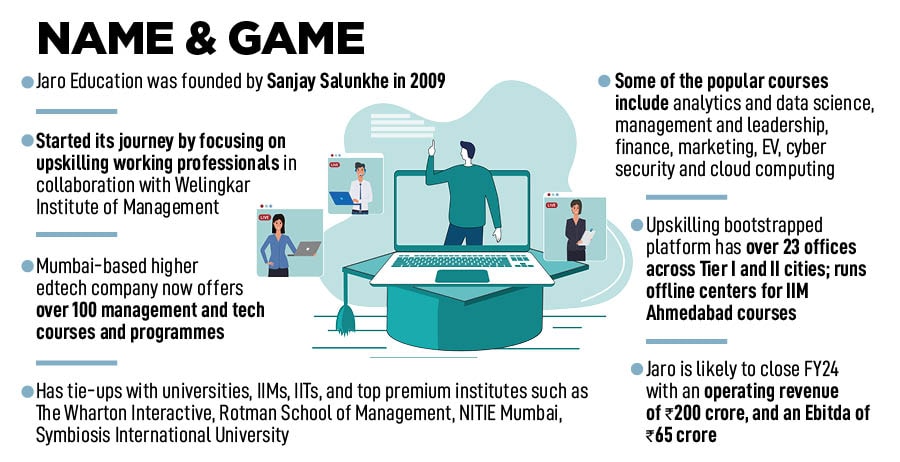

Jaro and an edtech masterclass

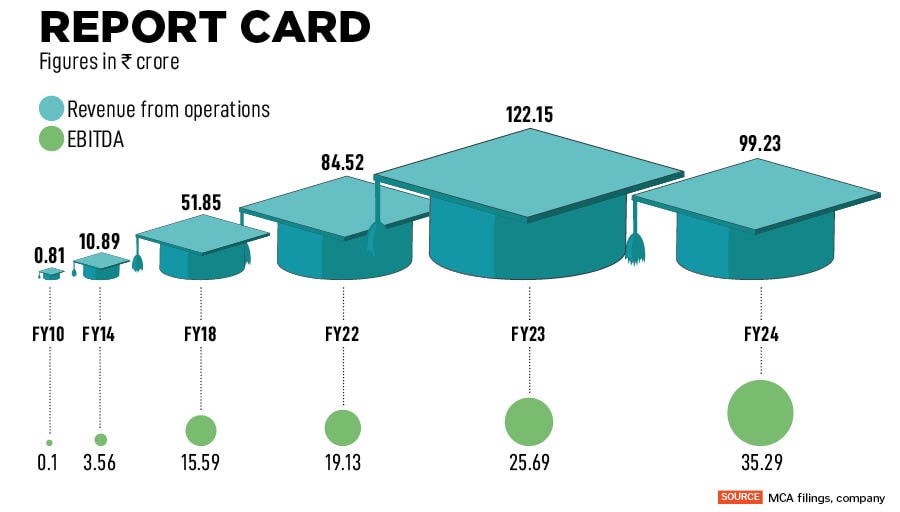

After a blockbuster IT hiring venture, a disastrous offline education joint venture, and three near-death experiences as an entrepreneur, Sanjay Salunkhe started Jaro in 2009. Fourteen years later, he has built over a Rs100-crore edtech upskilling company that is bootstrapped, scaling rapidly and profitable

Sanjay Salunkhe, Founder, Jaro Education

Image: Swapnil Sakhare for Forbes India

Sanjay Salunkhe, Founder, Jaro Education

Image: Swapnil Sakhare for Forbes India

“Knowledge is like an underwear,” Nicky Gumbel once reportedly remarked. “It is useful to have it but not necessary to show off,” the Anglican priest and author is widely attributed to have shared this nugget of wisdom. Back in India, for over two decades, a first-generation entrepreneur from Maharashtra never paraded his knowledge undies.

Born into a life of hardship—Sanjay Salunkhe’s father was a mill worker, mother was a homemaker, and he lived in a single room along with three siblings—the founder always practised humility. “This (humility) is what education teaches you,” says Salunkhe, who started IT hiring company NET HR in 1999, and after a decade, an online higher education company Jaro in 2009. “We are the edtech OG,” he laughs. Teaching, he adds, is a humbling experience.

Twelve years later, sometime in 2021, Salunkhe was about to learn a new lesson, and get to know a new brand: Unicorn underwear. “Dr Salunkhe, tell me your right price,” thundered one of the top edtech unicorn founders. “And doctor sahab, don’t exaggerate your finances. I know them,” the caller continued with his aggressive tone, pitch and intent to acquire upskilling edtech platform Jaro.

“I want to buy you out,” underlined the notorious bully, who had raised loads of capital, had a long list of global marquee venture capitalists on his cap table, and was all set to enter into the decacorn club (privately-held companies that are valued over $10 billion) with the next round of funding and valuation. It was 2021, the year that happened to be the peak of edtech funding—from $1.87 billion in 2020 to $5.82 billion in 2021--and a bunch of new-age edtech startups were busy using their war chest to either kill the competition or buy them out.