Pizza Cutter: Meet the master storyteller from Domino's

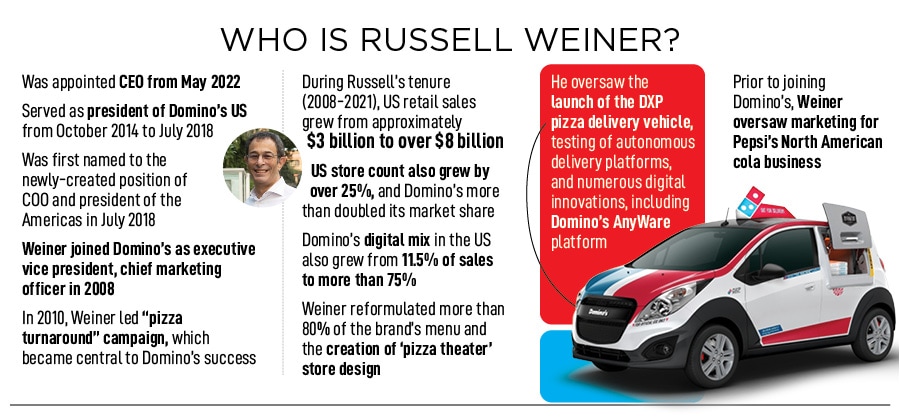

He once drove a taxi in New York City, was a vendor at Yankee Stadium, and delivered the New York Post for a living. Now as CEO of Domino's, Russell Weiner needs to bring the best of his hustle to navigate the uncertainties of a looming recession and a resurgence of the pandemic. Can he?

Russell Weiner, CEO, Domino’s

Image: Amit Verma

Russell Weiner, CEO, Domino’s

Image: Amit Verma

Ann Arbor, Michigan, US, December 2008. “Your pizza sucks…” the backhanded compliment was a sucker punch for Russell Weiner who was used to a “fizzy”, and “happy” life. He joined Pepsi in 1998, held various marketing positions over the next decade, and in 2007 urged cola drinkers to be “more happy”, a new tagline that Pepsi adopted since its last one—“Pepsi. It’s the cola”—in 2003. “One of the nice things about the word 'happy' is it's really multidimensional,” Weiner, vice president of cola marketing at PepsiCo, reportedly remarked during the unveiling of the advertising campaign with the new slogan. “The beauty of the word happy,” he underlined, “is it kind of captures all of them—invigorating, uplifting, exciting and fun.”

Then suddenly in December 2008, life turned ugly for Weiner. Just two months into his new job as executive vice president, chief marketing officer of Domino’s, his wife forwarded him a meme, which was floating freely on the internet. “We make our pizzas and our boxes out of the same material,” read the caustic message, which displayed two boxes of Domino’s. One was open and showed a pizza, and the other one was closed. Weiner didn’t know how to react. “Three months after I joined Domino’s, the stock hit a new low of under $3,” he recalls in an exclusive interview with Forbes India on his maiden visit to India as CEO in the third week of December. The new innings had nothing to smile, and say cheese!

Rewind to his decade-long stint at Pepsi, Weiner was indeed more than happy. For the marketing maverick, life was fun. He crafted Pepsi’s largest promotion in history—“Stuff”—a continuity programme rolled out to retain core Pepsi users, and his Diet Pepsi MAX ad campaign won an Effie Award for “Wake up People” in 2008. The same year, he was Brandweek's Top 10 Marketers of the Next Generation, and was also Advertising Age Top 40 under 40. The icing on the cake was Pepsi’s 2008 Super Bowl ad featuring Justin Timberlake, which emerged as the number one Super Bowl ad viewed online. Clearly, Lady Luck was smiling.

Fast forward to December 2008, Weiner’s luck was in shreds. Domino’s was into its third year of consecutive negative same store sales: 4.1 percent, 1.7 percent and 4.9 percent in 2006, 2007 and 2008, respectively. The celebrated marketer soon realised that the new brand he started working for had lost its fizz. The adjectives that the marketer passionately clung to all his life—invigorating, uplifting, exciting and fun—suddenly deserted him. And it was not a happy realisation at all.

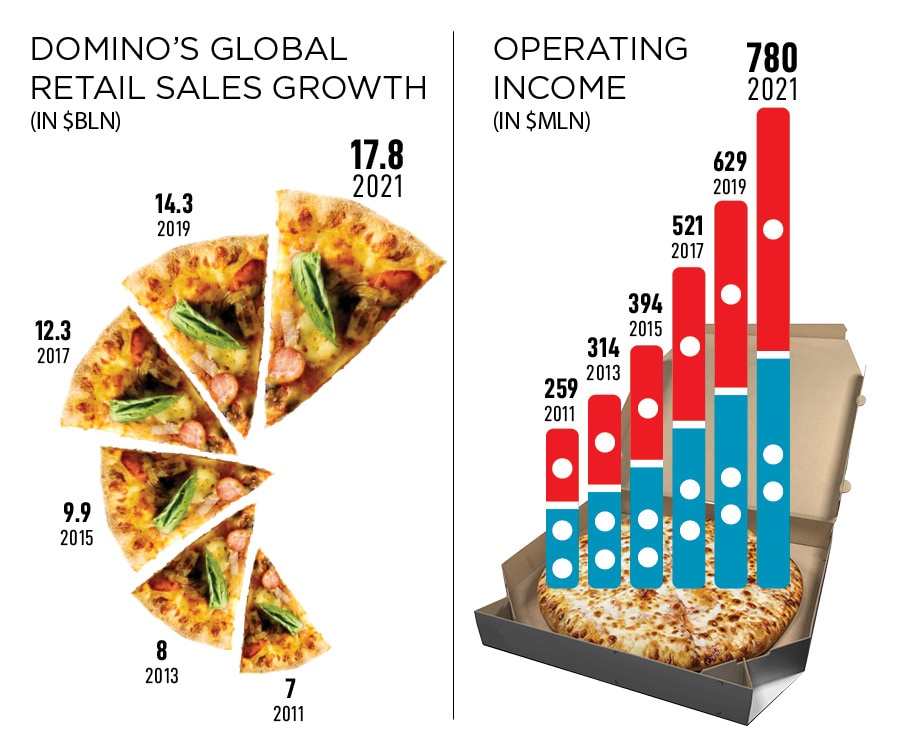

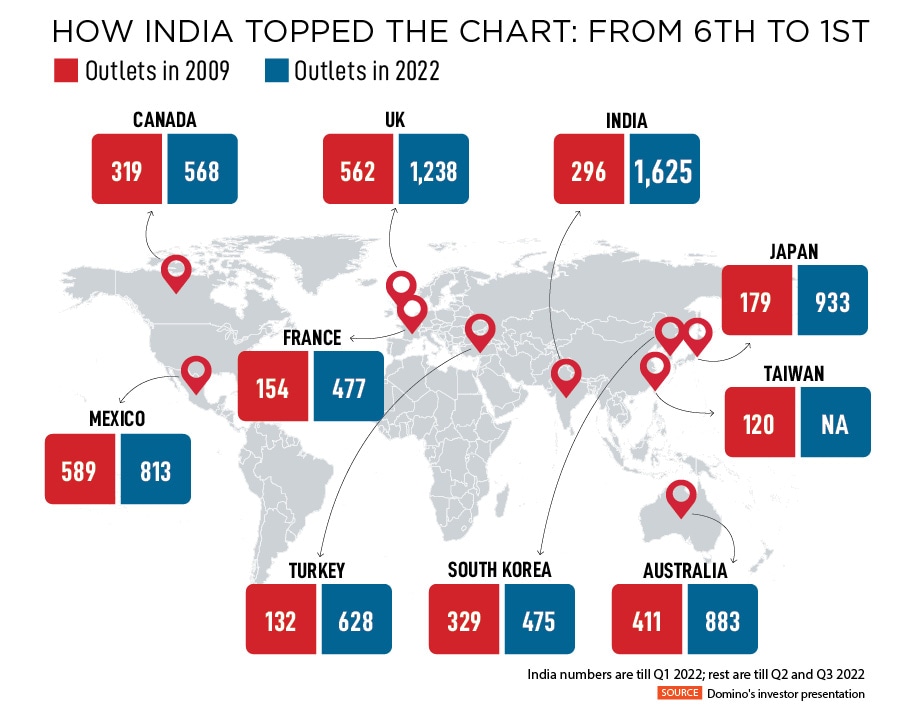

Weiner, though, is quick to add one more ingredient that went into making the secret sauce: A powerful storytelling. One of the things, he underlines, the restaurant industry doesn’t do well is they don't really tell stories. If one closes their eyes, and thinks of a fast food ad, it would be ‘here's the new product’, ‘now it's got extra this’ and ‘here's the price point’, and maybe a silly joke. “What we try to do at Domino's is tell stories about how we're trying to get better as a pizza company,” says Weiner, who was in India to roll out 20-minute delivery service by the pizza giant, which is now the biggest in the world.

Weiner, though, is quick to add one more ingredient that went into making the secret sauce: A powerful storytelling. One of the things, he underlines, the restaurant industry doesn’t do well is they don't really tell stories. If one closes their eyes, and thinks of a fast food ad, it would be ‘here's the new product’, ‘now it's got extra this’ and ‘here's the price point’, and maybe a silly joke. “What we try to do at Domino's is tell stories about how we're trying to get better as a pizza company,” says Weiner, who was in India to roll out 20-minute delivery service by the pizza giant, which is now the biggest in the world.

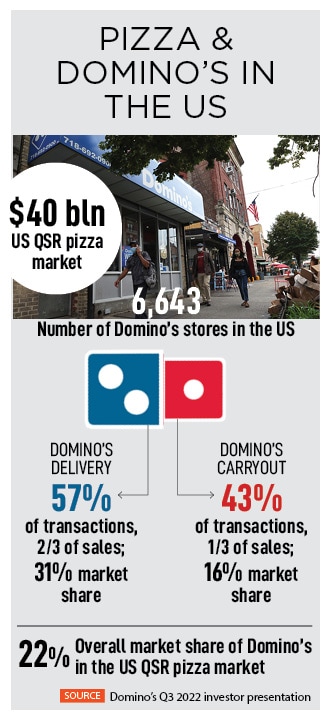

The challenges remain, though. A high rate of inflation will impact delivery. “Our research shows that relatively higher delivery costs might lead some customers to prepare meals at home,” he acknowledged in the earnings call. Weiner, though, was quick to weave in a positive story of hope. “In a world where consumer confidence is shrinking and inflation is high, Domino's will succeed,” he remarked, dishing out his reasons. First, the brand has managed to build strong profitable franchisees. Second, the team makes disciplined decisions based on insight. And lastly, he claims Domino’s has the digital supply chain and delivery expertise to offer best-in-class value and customer experience.

The challenges remain, though. A high rate of inflation will impact delivery. “Our research shows that relatively higher delivery costs might lead some customers to prepare meals at home,” he acknowledged in the earnings call. Weiner, though, was quick to weave in a positive story of hope. “In a world where consumer confidence is shrinking and inflation is high, Domino's will succeed,” he remarked, dishing out his reasons. First, the brand has managed to build strong profitable franchisees. Second, the team makes disciplined decisions based on insight. And lastly, he claims Domino’s has the digital supply chain and delivery expertise to offer best-in-class value and customer experience.