The Solitaire: Mithun Sacheti & the untold CaratLane story

From running out of money and coming menacingly close to going back to the family business in 2011, to being almost spooked by Nigerian scam, Mithun Sacheti has had his share of trials and tribulations. The founder, like a diamond, never cracked under pressure

Mithun Sacheti, Cofounder, CaratLane

Mithun Sacheti, Cofounder, CaratLane

New Delhi, 2011. The diamond merchant had a sneaky suspicion. “It has to be a Nigerian scam,” muttered Mithun Sacheti. “What kind of joke is this,” wondered the second-generation entrepreneur who was engulfed by a thick blanket of bemused disbelief. It had been two long years of fruitless toil for Sacheti who studied gemology in California, US; he came back to India in 2000 to join the family business of gems and jewellery in Mumbai, and after a month decided to move to Chennai to start operations in South India. In seven years, the business touched the Rs 80-crore mark, and had a Rs 10-crore profit. The family was impressed.

The young entrepreneur, though, was not dazzled either by a glittering bottom line or a glowing report card. He was frustrated with the fact that it took him seven years to open the second store in Coimbatore in 2007. “There was no pace. There was no scale. I wanted to expand,” recalls Sacheti, who was not a diamond in the rough but was also not shining the way he wanted to. “I thought the internet is a great place as it can flip the problem of scale,” he underlines. Though well aware of the flip side of venturing out of the family business, Sacheti mustered courage and shared his desire with the patriarch. “Who leaves the family business?” asked a bewildered father, who started a jewellery store, Jaipur Gems, in Mumbai in 1974. “You have done exceedingly well,” he underlined. “And you are the best performer in the family,” he lavishly praised his son.

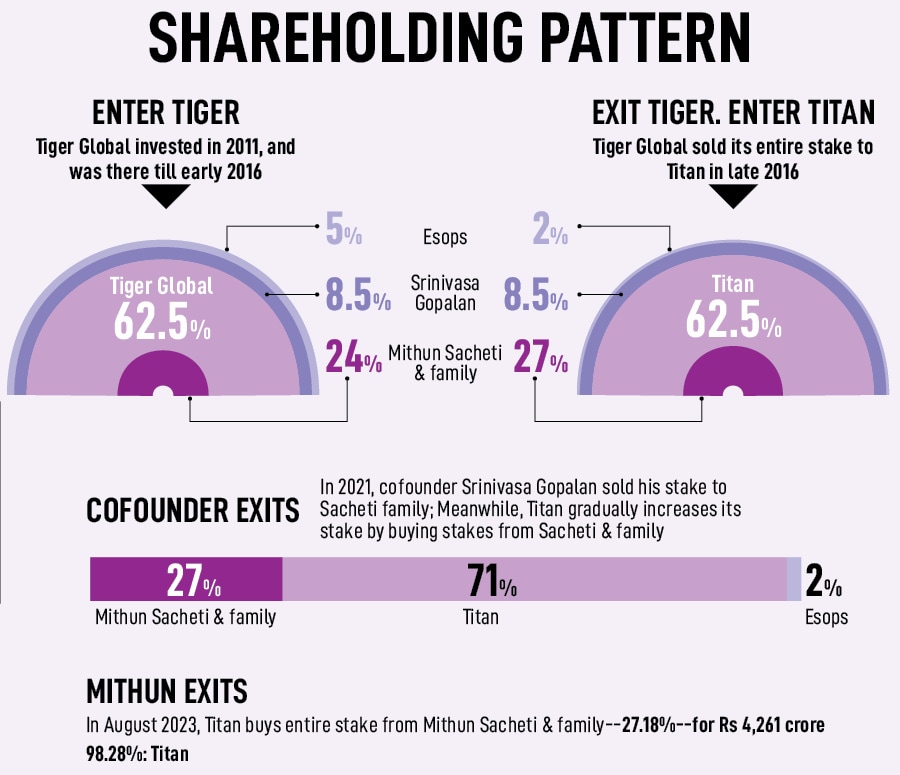

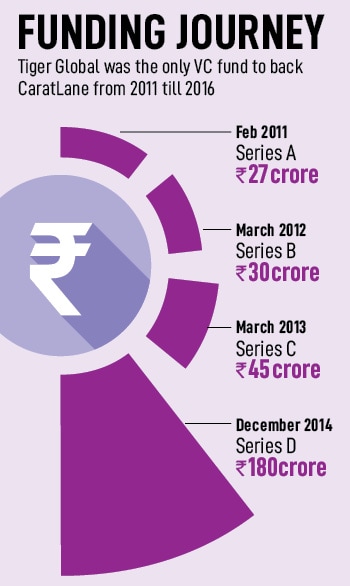

Sacheti, though, had made up his mind. “Please give me Rs 75 lakh and four years,” he made a passionate plea to his father. “If I don’t succeed, I will come back and join the family business,” he promised. His dad displayed a heart of gold, Sacheti got Rs 74 lakh, his co-founder Srinivasa Gopalan chipped in with Rs 26 lakh, and the duo started CaratLane in 2008.

The diamond, though, was turning out to be a lump of coal. “We made the website, but there was no sale for 15 days,” recalls Sacheti. Over the next few months, the business started trudging. But what made the journey exceedingly aggravating was loads of scepticism from a large tribe of cynics. “It’s a terrible idea. Band kar do [shut it down],” was how a top businessman in Chennai reacted. There were naysayers everywhere. During his frequent visits to Mumbai to attend trade events, Sacheti would shy away from introducing his company. “Hanste they sab mere upar, kaun khareedega online [Everyone laughed at me; who will buy online],” he recounts.

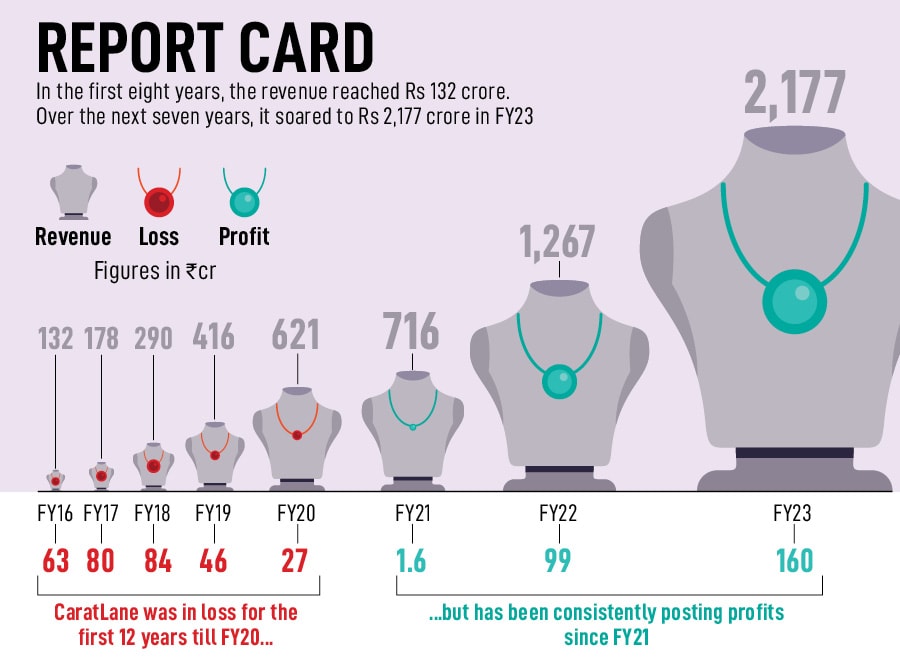

A year later, things, though, didn’t move the way Sacheti imagined. He was feeling suffocated. He explains why. “I was getting drowned by my own noise, my own expectations,” he says. Having Tata as the Big Brother, Sacheti hoped for a faster and aggressive growth. “The frustration was from my expectations, and not from what Titan was doing,” he maintains. The founder was mulling about his future, his co-founder too was uncertain about the prospects, and CaratLane seemed to have lost its way in the perpetual loss-making bylanes.

A year later, things, though, didn’t move the way Sacheti imagined. He was feeling suffocated. He explains why. “I was getting drowned by my own noise, my own expectations,” he says. Having Tata as the Big Brother, Sacheti hoped for a faster and aggressive growth. “The frustration was from my expectations, and not from what Titan was doing,” he maintains. The founder was mulling about his future, his co-founder too was uncertain about the prospects, and CaratLane seemed to have lost its way in the perpetual loss-making bylanes.