Why the RBI MPC may give growth a chance, again

The Monetary Policy Committee has been incrementally supporting growth by holding interest rates at historically low levels. But is it risking future growth by accommodating high inflation for so long?

The growth-inflation trade-off is at a critical point. Inflation has crossed RBI’s upper threshold of 6 percent at a time when durable recovery in the domestic economy is at a nascent stage

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur

The growth-inflation trade-off is at a critical point. Inflation has crossed RBI’s upper threshold of 6 percent at a time when durable recovery in the domestic economy is at a nascent stage

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur

The Reserve Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) will find itself batting on a sticky wicket in its first meeting of fiscal year 2023 as it faces the deepening complexities of rising inflation and sliding growth. So far, the central bank has stuck to its game plan of nurturing the feeble signs of growth, and has refrained from altering its accommodative policy stance, despite the persistent increase in price levels.

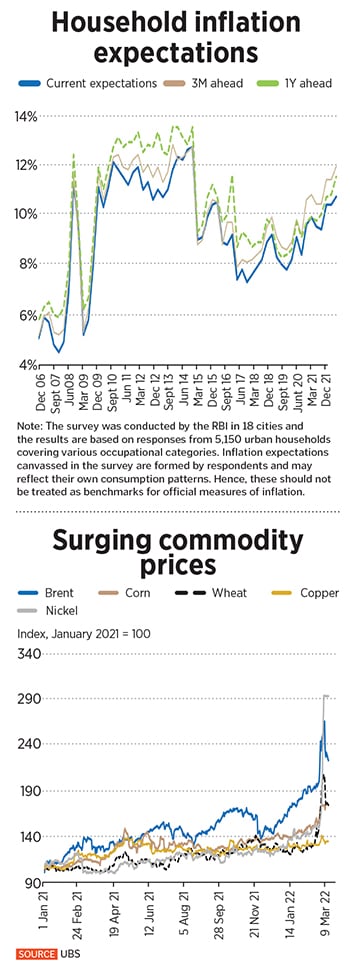

But the supply disruptions and price shocks arising from the Russia-Ukraine war have made a challenging macroeconomic situation much more difficult. Now, the level of uncertainty has multiplied manifold, and forecasting near-term economic outcomes is tricky.

“The greatest risk in the near term is the potential for policy error,” says Steve Cochrane, chief economist, APAC, Moody’s Analytics.

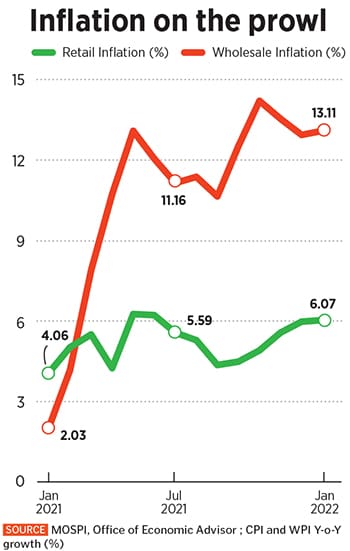

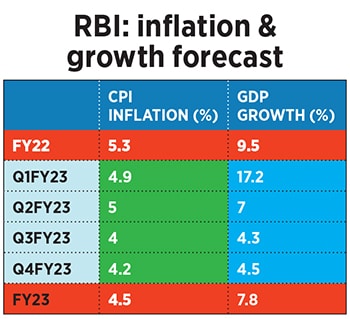

The growth-inflation trade-off is at a critical point. Inflation has crossed RBI’s upper threshold of 6 percent (see chart) at a time when durable recovery in the domestic economy is at a nascent stage. Most economists are wary that the ongoing rise in commodity prices will further add to inflationary woes that could plug growth in the coming quarters.

Sonal Varma, MD and chief economist, Nomura, says inflation expectations in the last two years have gone up. “Our worry is this is going to be the third year of elevated inflation which is broadening out. The risk of generalisation of inflation and it gradually spilling over to wages is growing, and we are now at a point where inflation itself is going to become a negative (factor) for growth.”

“Ultimately monetary policy has to do a cost benefit analysis; how much are we incrementally supporting growth through our policies versus how much are we risking future growth because of accommodating a higher inflation for so long. It is better to move early than having to do a larger pivot down the line,” explains Varma.

“Ultimately monetary policy has to do a cost benefit analysis; how much are we incrementally supporting growth through our policies versus how much are we risking future growth because of accommodating a higher inflation for so long. It is better to move early than having to do a larger pivot down the line,” explains Varma.  Economists have revised their inflation target upwards in light of the volatility in the commodity price cycle in the backdrop of high uncertainty.

Economists have revised their inflation target upwards in light of the volatility in the commodity price cycle in the backdrop of high uncertainty.

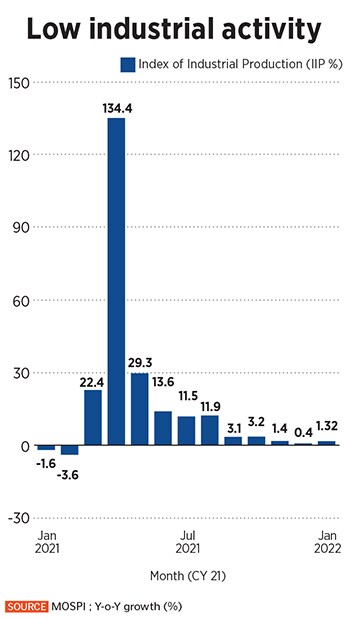

Importantly, the investment cycle needs to kick-start to spur durable recovery. Most manufacturing hubs are not operating at full capacity utilisation levels, thereby pent-up demand may not be sufficient to incentivise fresh investments for expansion.

Importantly, the investment cycle needs to kick-start to spur durable recovery. Most manufacturing hubs are not operating at full capacity utilisation levels, thereby pent-up demand may not be sufficient to incentivise fresh investments for expansion.  Bhattacharya says there are anecdotal indications of capex plans among MSMEs. He points to strong exports, ancillary signals like bank credit and e-way bills to suggest an uptick in economic activity. “We forecast India’s FY23 GDP growth at 7.8 percent, but there is a strong downside risk to this, which is difficult to quantify given the extreme uncertainty at present,” he adds.

Bhattacharya says there are anecdotal indications of capex plans among MSMEs. He points to strong exports, ancillary signals like bank credit and e-way bills to suggest an uptick in economic activity. “We forecast India’s FY23 GDP growth at 7.8 percent, but there is a strong downside risk to this, which is difficult to quantify given the extreme uncertainty at present,” he adds.