Xiaomi is betting big on premium. Can the smartphone maker succeed?

A recoil in the budget share of smartphones, a disproportionate reliance on online channels, and the lack of premium phones took a toll on Xiaomi's market share over the last two years. Now, the Chinese budget warrior is getting back into the game with a premium play. Can it upgrade to an aspirational brand?

Muralikrishnan B, president Xiaomi India.

Image: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India

Muralikrishnan B, president Xiaomi India.

Image: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India

The characters were real, and the story was non-fiction. The events, though, had a strong resemblance to fiction.

In July 2014, over one lakh potential buyers scrambled to register for the flash sale on ecommerce platform Flipkart. And within five seconds, thousands of smartphones were scooped up by fervent consumers. A month later, in August, the frenzy erupted again when the same model—thousands of Xiaomi's Mi3 phones—was sold out in two seconds. Even over thirty days later, the excitement persisted. This time, Xiaomi sold 40,000 units of Redmi 1S in four seconds. The Chinese smartphone maker had made its India debut in July 2014, and flash sales by the upstart set the market on fire. The euphoria was real, but the experience was surreal. In 2014, when handset brands were wooing buyers in shops, Xiaomi was engaged in an intense online romance.

The fairytale continued. “The first four-five years were like Midas touch for us,” recalls Muralikrishnan B, who joined the Chinese brand as the chief operating officer in 2018 and four years later was elevated to president in July 2022.

A decade ago, the smartphone market was nascent, the competition was placid, and Xiaomi had something that others lacked: Budget phones for the masses. Muralikrishnan explains. “We had the right product for the right market, at the right price and at the right time.”

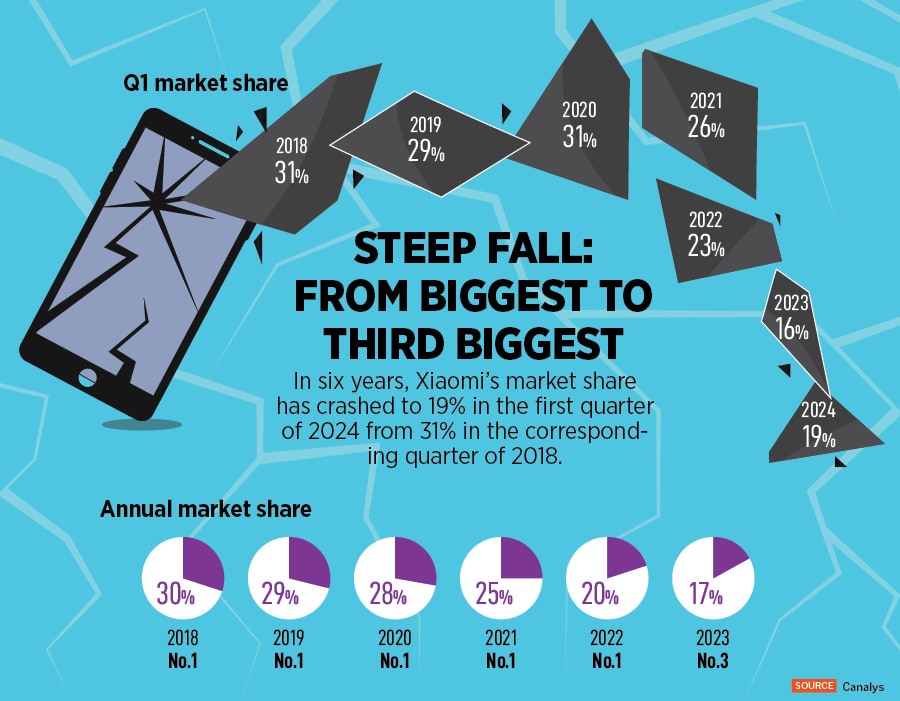

India was warming up to 4G but homegrown mavericks like Micromax, Intex, Lava, and Karbonn were saddled with a massive 3G inventory. “We started with a clean slate, went aggressive with 4G handsets, and things changed over time,” he underlines. In little over three years, Xiaomi became the biggest in India and grabbed a meaty 30 percent market share in 2018. In fact, the brand logged a record 31 percent share in the first quarter of 2018. “This is the stuff that fairy tales are made up of,” smiles Muralikrishnan. “But every fairy tale has an element of drama.”

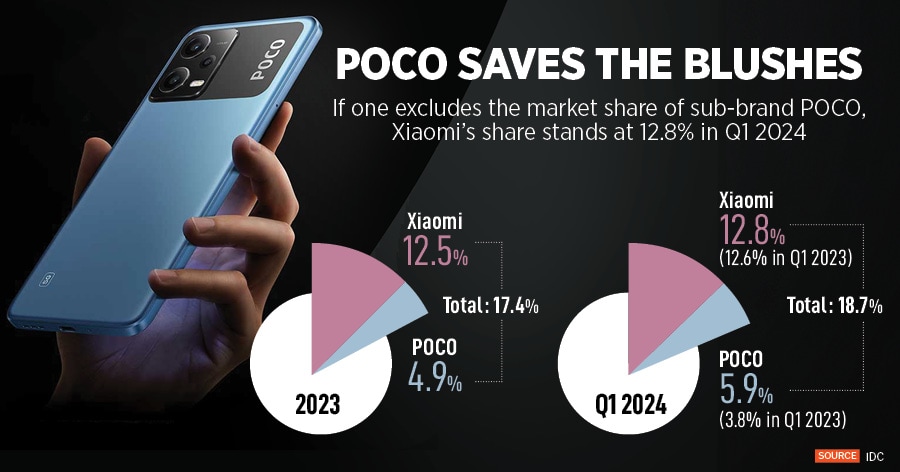

From a record 31 percent volume market share in the first quarter of 2018, Xiaomi slipped to 16 percent in the corresponding quarter of 2023. A year later, it inched to 19 percent. The annual report card too reflected the grim reality. From a 30 percent market share in 2018, Xiaomi tumbled to 17 percent in 2023. A player that occupied the top slot for 20 consecutive quarters, made way for Samsung in the third quarter of 2022.

From a record 31 percent volume market share in the first quarter of 2018, Xiaomi slipped to 16 percent in the corresponding quarter of 2023. A year later, it inched to 19 percent. The annual report card too reflected the grim reality. From a 30 percent market share in 2018, Xiaomi tumbled to 17 percent in 2023. A player that occupied the top slot for 20 consecutive quarters, made way for Samsung in the third quarter of 2022.