How Bira 91 went from craft brew to the small-town's drink of choice

"A stronger brew helped Ankur Jain transform Bira 91 into a player that's getting most of its growth from the hinterlands"

Ankur Jain, founder, B9 Beverages, maker of Bira 91

Ankur Jain, founder, B9 Beverages, maker of Bira 91 Image: Madhu Kapparath

On Christmas eve, around 2.30 pm, Channegowda was about to make a bold move. “Onedu strong beku (give me a strong beer),” requested the 32-year-old electrician. The retailer stared back. “Are you inspired by Virat Kohli?” he asked, alluding to the huge billboard of the Indian cricket captain that greets consumers at the Sri Kalikamba Wines Store in Baburayanakoppal village, some 130 km from Bengaluru. The hoarding of Royal Challenge sports drinks, endorsed by Kohli, flashes the brand’s signature message: Make a bold move.

“Virat strong beda, bunder strong beku (I don’t need Virat strong. Give me monkey strong),” Channegowda replied, pointing to a bottle. “It’s Boom and has a quirky monkey head,” his friend chipped in, who induced Channegowda into shunning his old beer brand. “Idu tumba tasty mattu strong (This is different, tasty and strong),” he insisted.

Another 40 km from Baburayanakoppal is Kwality Spirits, a wine retail shop that has a singular distinctive identity: A massive advertisement of Knock Out, a beer brand owned by SABMiller. Lokesh, a painter, is enjoying a chilled beer in a steel glass. “Beer mugs are for the cities. Here you get the monkey drink in a glass,” he says, pointing to a bottle of Boom, a strong beer brand he got hooked on to six months ago. “It gives me a kick,” he says.

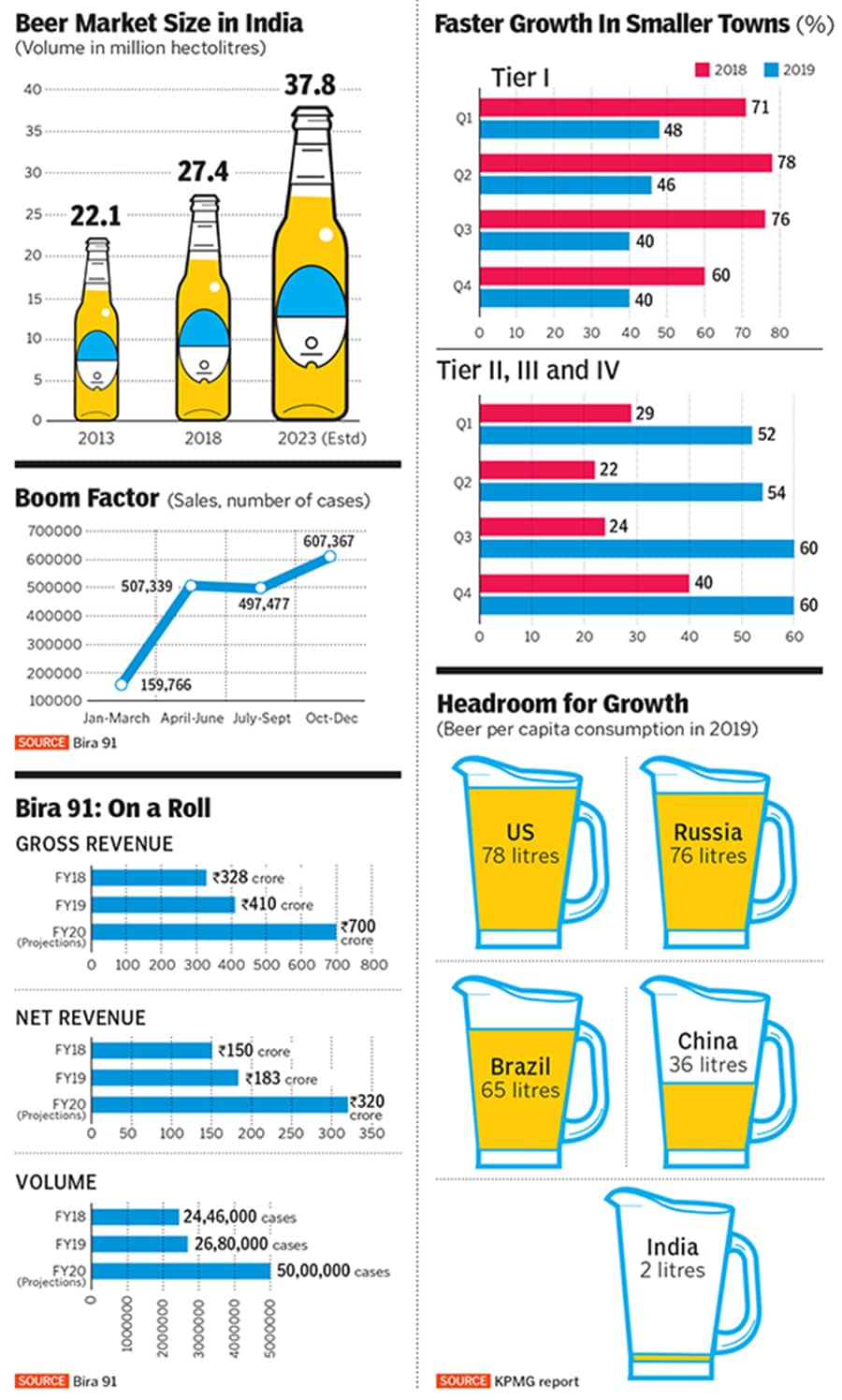

“Welcome to Karnataka. It’s Boom time,” says Vikash Bakrewala, division director (south) of B9 Beverages, the maker of Bira 91 and Boom beer. “We have just started. The pace and the reach are set to accelerate,” he says. Bira 91 got 60 percent of its sales from Tier II cities and beyond in the last two quarters of 2019 compared to 24 percent and 40 percent in 2018’s corresponding quarters. From 159,766 cases of Boom—its strong beer brand launched last February— sold in the first quarter of last year to 607,367 cases in the last quarter, the monkey jump has been staggering.

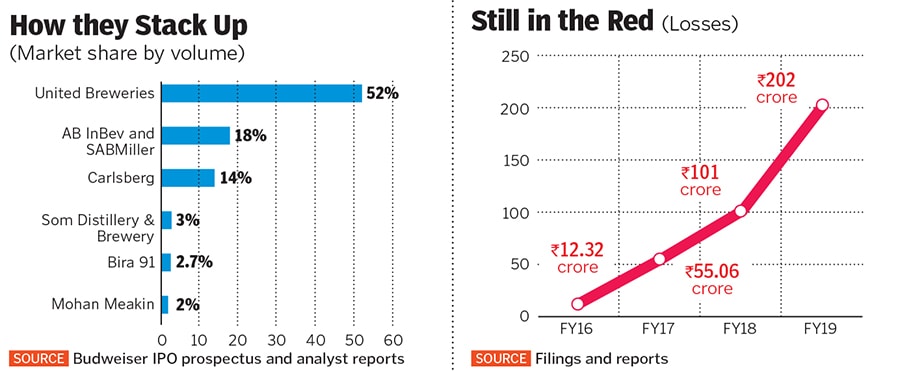

With over 85 percent of the beer market in India dominated by strong beer—with alcohol content between 6 percent and 8 percent—Boom is helping Bira 91 make a transition from a craft beer brand to a player that’s getting most of its growth from smaller cities and towns. What Boom has also done is enable Bira 91 to expand aggressively—from 56 cities at the start of the year to 386 cities now—and become the fifth biggest beer maker in India with 2.7 percent value market share.

For a brand that began its innings in February 2015 in Delhi, the journey has been phenomenal: From a paltry gross revenue of ₹50 lakh in fiscal 2016 to striking a run rate of ₹700 crore for the financial year that ends in March 2020; from a presence in 60 outlets to reaching a little under 29,000 by end-March; and from selling in one country to now being present in 16.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)

Boom is helping Bira 91 establish its presence in smaller cities and towns

Boom is helping Bira 91 establish its presence in smaller cities and towns