Inside Puma's sprint past Adidas in India

India is the only country in which German sportswear maker's Big Cat is bigger than its global arch-rival, Adidas

Image: Puma

It was early 2006. After spending three years with Reebok India, Abhishek Ganguly was set to join a German sportswear rival, which was debuting in India 13 years after Reebok set foot.

But the first question at his exit interview dampened the spirits of the IIM-Lucknow alumnus, who was then 26 years old. “Tu kitna bana lega (how much will you make from this brand)?” asked a senior human resource (HR) official. The condescension towards an upstart was perhaps understandable. Despite a global buyout by Adidas in 2005, Reebok still lorded over the India market. “Who knows Puma here?” asked another HR honcho. “It won’t even be a ₹50-crore brand in five years.”

Ganguly was shaken. “I believe it’s a great brand and the Indian market needs it,” he said politely. It was clear that the historic rivalry between Germany’s Dassler brothers was about to play out in India. The duo founded sports shoe company Gebruder Dassler OHG in 1924 until, 24 years later, when the elder sibling, Rudolf, parted ways to start Puma. A year later, in 1949, younger brother Adolf (Adi) founded Adidas.

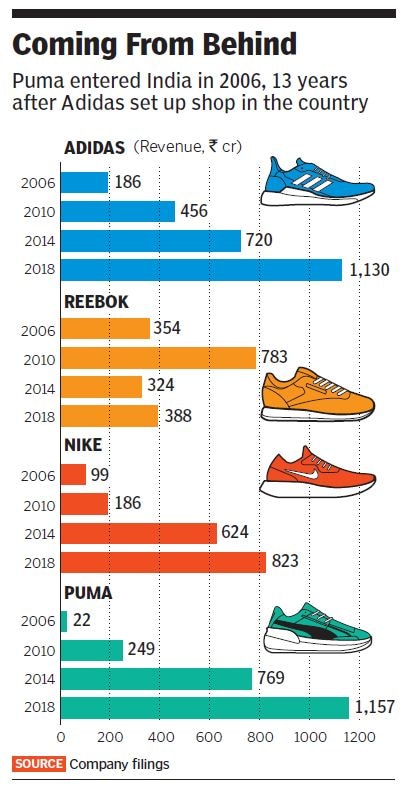

In India, Puma came after Adidas, and began with a modest revenue of ₹22 crore in 2006. Reebok by then had an imposing top line of ₹354 crore, ahead of Adidas at ₹186 crore and Nike at ₹99 crore.

Fast forward to 2020. In 13 years, the Big Cat has leapt ahead. Puma posted revenues of ₹1,413 crore in 2019, the second consecutive calendar year in which it has sprinted ahead of its competitors. Reebok and Adidas, which follow a March-end fiscal year, were at ₹407 crore and ₹1,250 crore respectively in fiscal 2019. Nike reported revenues of ₹831 crore for the same period, according to the Registrar of Companies (RoC) filings by the brands. However, a more accurate comparison of Puma’s year-ended December 2019 numbers with those of the rest would be once the competitors release their numbers for the year-ended March 2020.

At the corporate headquarters of Puma India at Indiranagar in Bengaluru, a huge portrait of pugilist and six-time world champion MC Mary Kom looms over the entrance of the four-storeyed building. Inside, another brand ambassador, eight-time Olympic gold medallist and 100 mt world record-holder sprinter Usain Bolt gazes intensely from a poster. Giving him company, fittingly, is arguably the best modern cricketer and Indian cricket captain Virat Kohli—the face of the brand since 2017—a move that global chief executive officer credits to the local leadership.

On the third floor, Ganguly, the managing director of Puma India, is firmly ensconced in a plush red sofa in one of the meeting rooms that has a picture of American singer and actor Selena Gomez on one of its walls. “When people said the economy is slowing down, we grew by 22 percent,” he says. Last year, Puma signed the highest number of brand ambassadors. “I don’t know how many brands have grown so much in a slowdown year.”

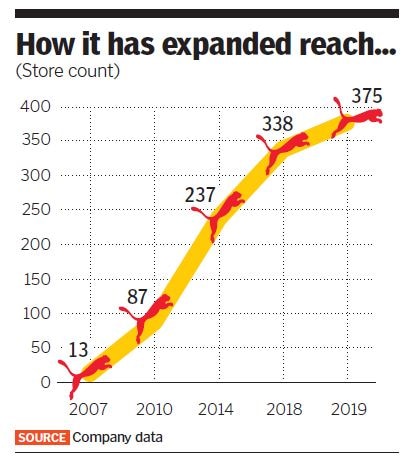

Defying norms, much like its latest brand campaign of ‘Propah Lady’—which showcases how boxer Mary Kom, athlete Dutee Chand, actor Sara Ali Khan and transgender model Anjali Lama shattered stereotypes—has helped the brand take a huge leap last year. The biggest problem of a slowdown, Ganguly maintains, is not consumer sentiment. “It’s business sentiment,” he says. Businesses go on the back foot, there is a freeze on hiring, marketing costs are chopped, plans to open new stores are shelved and less inventory is added. “We went against the conventional wisdom,” he adds. The brand opened 47 stores last year, doubled its marketing spend, bought more inventory to grow its size and invested heavily in a customer relationship programme. The results were for everyone to see. Puma, he says, has added ₹250 crore in one year, which is roughly half the size of Reebok.

There are a number of levers, reckon marketing experts, which Puma is using as a challenger brand. It is going after market share in a clearly defined segment: The lifestyle dresser. India, says Jessie Paul, founder of Paul Writer, a marketing advisory firm, has a much larger lifestyle footwear market than athletic footwear. So carving out even a small percentage is big in volume terms. To build on its casual dressing position, Puma has invested in non-sports properties like Sonic the Hedgehog, a video gaming legend. “It has cleverly directed and concentrated its ad spends for maximum impact,” she says. Choosing Virat Kohli as a brand ambassador was a clever thing to do. “It appeals to a mass millennial audience,” adds Paul. Overall, its strategy is to focus on a youth audience and then pursue each campaign with the full power of digital.

What also gives Puma an edge over its famed rivals is its appeal. While all brands make similar products, Adidas and Nike are purely in the sportswear category, while Puma is a ‘style and leisure’ sportswear company, says N Chandramouli, chief executive officer at Mumbai-based TRA Research. The millennial buyer, he explains, wants to find a brand that expresses their aspirations. The Puma buyer is younger and more style conscious than that of Nike or Adidas. From the brand’s persona to its engagement with consumers, all are reflective of why Puma finds better acceptance with the younger generation. “Puma’s positioning is the reason it fits into young India’s aspirations, and therefore its growing market,” says Chandramouli. Puma, he predicts, will grow at a much faster pace over the next five years.

The journey of the challenger brand, though—from ₹22 crore in 2006 to ₹1,413 crore in 2019—was not easy. From being shunned by multi-brand retail stores to being mocked at by big-pocket offline retailers who used to dictate terms to foreign brands to struggling to find ‘cheaper’ space to open stores, Puma didn’t come in the consideration set of any stakeholders—traders as well as buyers. “Will you pay me rent on time?” asked one of the mall owners in Bengaluru when Ganguly tried to hunt for retail space. “Get me an assurance email from your global head office. I hope you won’t disappear overnight,” was how the landlord abruptly ended the meeting.

Ganguly didn’t disappear. Nor did the brand. Both persisted, and crisscrossed large parts of the country looking for takers. Like a possessed salesman, he used to stuff all shoes in his Tata Indica and keep pitching to offline retailers. Ecommerce channels were almost non-existent. Every order, however small, was cheered. “When I got my first ₹10 lakh cheque from a retailer, I celebrated with my chief financial officer,” he recalls.

Struggle also brought in its wake the first set of mistakes, and learnings. Puma’s first set of customers—multi-brand retailers—never stayed with the brand. This promiscuous behaviour led Ganguly to focus more on solo branded stores. Focus was now shifting on consumers rather than the traders. Over the last few years, contribution from ecommerce is over a quarter of total sales.

The second mistake was to do more with Ganguly, who had hired people from his previous organisations at a hefty package. If the idea was a quick fix, it backfired. “It was a complete disaster,” he says. Reason: The executives coming from a leader company didn’t have the mindset to work in a ‘startup’ like Puma. “They didn’t step out of the comfort zone or think out of box.”

What also came along was quick learning. The most crucial was to spot an opportunity in a consumer segment that most of the brands didn’t focus much on: Women. “Our sales are growing much faster in the women’s category,” Ganguly points out. Apart from having a battery of women brand ambassadors, Puma started wooing women buyers too. What this means is more space for women products at stores, and more women-specific marketing and advertising campaigns. “Focusing on women is a crucial part of our strategy,” he says. Opening large format stores in top cities was another gambit that paid off. “It was an expensive risk. But it worked out.”

Can Puma maintain its pace of growth? Ganguly sounds confident. Being a market leader is an outcome, not an objective. “My biggest ambition is to ensure that there is not a single year of a blip—a fall in sales,” he says. The task, though, is not easy given that the disruptor can also get disrupted. “You can be destroyed if you don’t evolve, and behave like a newcomer.” The question now is not ‘tu kitna bana lega?’ but ‘tu aur kitna bana lega (how much more will you make)?’ “We came from behind by looking ahead. We need to keep running,” he says. The Big Cat, he promises, will always be on the prowl.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)