Parag Milk Foods: Whey to go

Akshali Shah is giving Parag Milk Foods, India's second biggest cheese maker, a protein makeover. Will the second-gen entrepreneur's gambit pay off?

Akshali Shah, Senior vice president (Strategy, Sales and marketing) and Devendra Shah, Chairman and founder, Parag Milk Food

Akshali Shah, Senior vice president (Strategy, Sales and marketing) and Devendra Shah, Chairman and founder, Parag Milk FoodImage: Mexy Xavier

Sunil Rathi, a budding wrestler in Badshahpur village, over 60 km from Delhi, starts his day with a glass of cow milk. Rathi, six-foot-something and weighing 85 kg, has plastered his bedroom with pictures of bodybuilder-turned-actor Arnold Schwarzenegger, flexing his muscles. His favourite is the one stamped on the door, where Schwarzenegger’s veins threaten to pop out of his arms and the frame. “Milk alone can’t get you such a monstrous shape. It has to be protein,” Rathi, 21, says, as he grabs a yellow jar lying on his table. He scoops out some powder from it, mixes it with water and gulps it down. Avvatar, a whey protein brand from Parag Milk Foods, happens to be Rathi’s daily dose of dietary supplement.

Cut to the western suburb of Vile Parle in Mumbai. Shiva Sardesai, a chartered accountant and a vegetarian, was introduced to protein supplement ‘Go Protein Power’, another product from the Parag stable, last December by his neighbourhood chemist. Though the plan was to take care of the protein deficiency he was diagnosed with early last year, Sardesai, 40, also made his 10-year-old daughter try the product. “I was surviving on carbs. It never hit me that protein would matter so much.”

About an hour’s distance from Vile Parle, at Parag Milk Food’s corporate headquarters in Nariman Point, Akshali Shah, its senior vice president (strategy, sales and marketing) knows the significance of protein. “It,” she says, “is going to be one of the biggest growth drivers for us.” Second-generation entrepreneur Akshali has been stealthily transforming Parag Milk Foods—India’s second biggest cheese maker with ‘Go’, and largest cow ghee producer with ‘Gowardhan’—into a protein powerhouse.

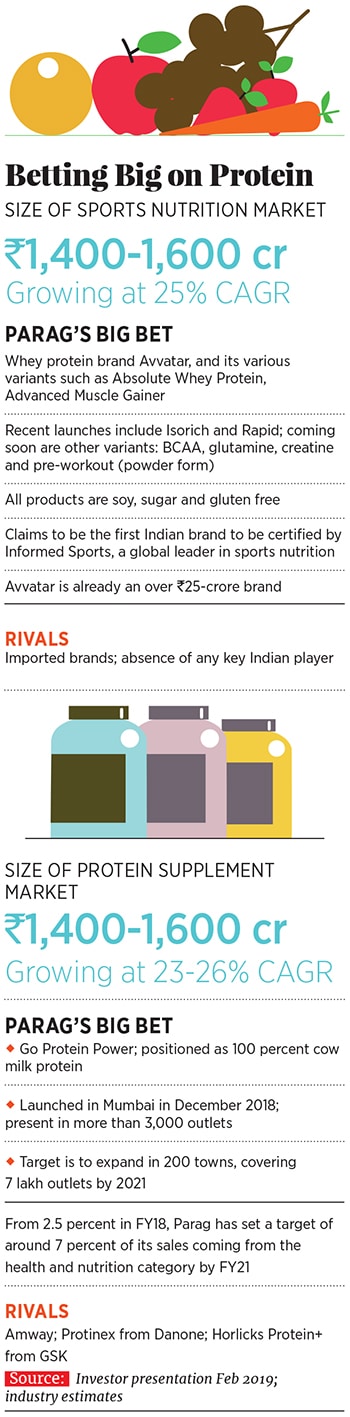

From rolling out ‘Go Protein Power’, which takes on the likes of biggies such as Amway, Protinex from Danone and Horlicks Protein+ from GSK, in Mumbai last December to aggressively pushing Avvatar and its recent muscle and mass gainer products across the country, the 28-year-old is savouring the nascent taste of her business strategy. “Protein is also a high-margin game,” she says, as she drinks Topp Up, a flavoured milk brand made by her company. Started in 1992 by her father Devendra Shah to sell milk and skimmed milk powder, it had a modest beginning; it got listed in 2016, and closed FY18 with a revenue of ₹1,955 crore.

PROTEIN SHOT

From a paltry 2.5 percent of sales coming through the health and nutrition category in FY18, Parag plans to double it to 7 percent by fiscal 2021. Leading from the front is Avaatar, which has become a ₹25-crore brand. Billed as India’s first whey protein brand to be milked, processed and packed within 24 hours, Avvatar also claims to be soy, sugar and gluten free. Joining the protein brigade is another brand ‘Go Protein Power’. Positioned as 100 percent cow milk protein, it is present in more than 3,000 outlets across Mumbai. The target is to expand it to 200 towns, covering 7 lakh outlets by 2021.

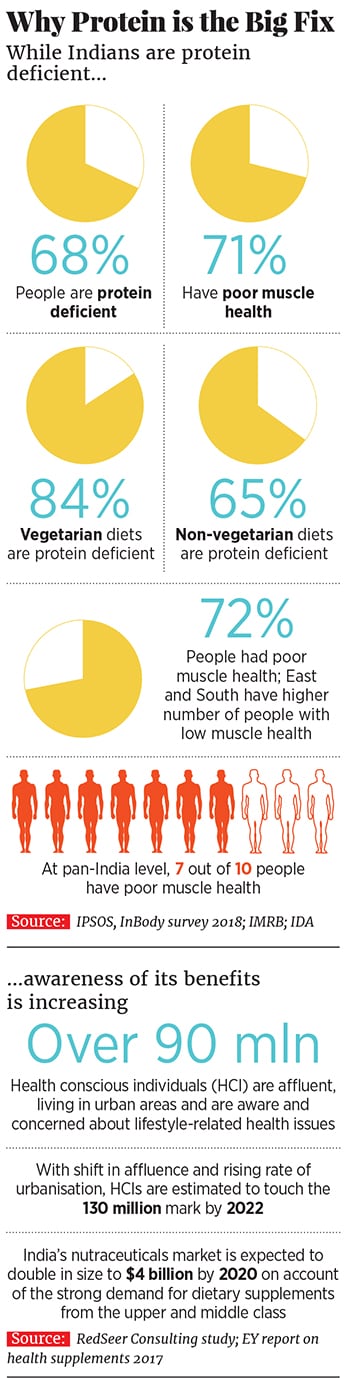

For Parag Milk Foods, which already gets 66 percent of its revenue from value-added products—mostly cheese and ghee—betting heavily on the protein market makes business sense. Akshali explains. The size of the sports nutrition market, she lets on, is estimated at ₹1,400-1,600 crore, and is growing at 25 percent CAGR. “There is no major Indian player in this segment,” she says. There’s another lucrative segment—the protein supplement market. Though this has many foreign players, the headroom for growth is immense given Parag’s distribution reach of over 3 lakh retail outlets across India.

Underlining Akshali’s attempt to take Parag deeper into the protein business is the fact that Indians are largely protein deficient. “Eighty-four percent of vegetarian and 65 percent of non-vegetarian diets are protein deficient,” she says, citing a study carried out last year.

Though the trigger to enter the whey protein segment was the frequent sighting of Indians carrying huge jars of imported brands at airports, the move was driven by a business opportunity that the making of cheese offered. Whey is the liquid part of milk that separates during cheese production. “We are the only Indian company to make fresh whey protein from our dairy farm to your shaker cup,” she avers.

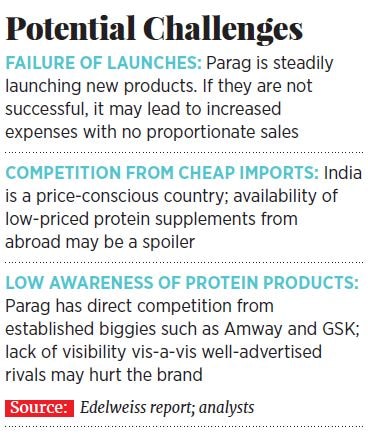

Though the protein supplement market is growing at a fast clip, it will take a few years for it to reach an inflection point, reckon retail and food experts. “It is still early days for protein shakes and supplements,” says Rajat Wahi, partner at Deloitte India. While conceding that increasing awareness and knowledge about health and wellness, weight loss programmes through high protein diets, and importance of protein diets—especially for vegetarians—will push the frontiers of the market, Wahi stresses there are two stumbling blocks for widespread adoption of protein: High price points, and the lack of availability and distribution. “As prices come down and availability increases, the market will grow faster and reach an inflection point in the next two to three years,” he adds.

Akshali, for her part, is in no hurry, and dismisses the idea of ‘unaffordability’. Take, for instance, premium milk brand ‘Pride of Cows’, which was recently launched in Delhi and for which the company will airlift milk from its dairy farm near Pune and sell it in Delhi-NCR at ₹120 a litre. Regular milk costs ₹40-50 a litre in the capital. “We are already selling an average of 34,000 litres of premium cow milk directly to customers in Mumbai, Pune and Surat,” she adds.

REVISITING THE CHEESE GAMBIT

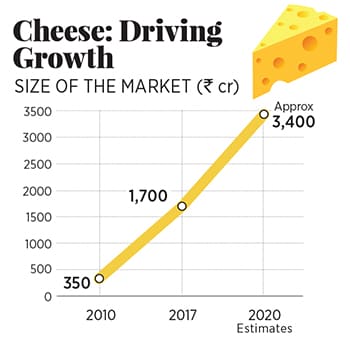

Being adequately prepared for take off at the right time, reckons Akshali, is what matters the most. “History repeats,” she grins, alluding to the bold gambit taken by her father in 2008.

A decade back, the cheese market was dominated by the two big daddies of dairy: Amul and Britannia. There was also a large unorganised cheese market, mostly made up of imported stuff. While Amul and Britannia had a combined capacity of an estimated 600 metric tonnes per month, Shah decided to set up a 1,200 metric tonne plant. “People branded us crazy. Most of our rivals and industry veterans mocked us,” the senior Shah recounts. Reading the market dynamics better than others, he reckons, is what helped him in taking a huge leap of faith.

Parag’s cheese play coincided with a time when the quick service restaurant (QSR) industry was about to experience a strong tailwind in India. Shah sensed the impending shift. The cheese market, eventually, did explode as a battery of multinational as well as homegrown players hopped on to the burger and pizza bandwagon. What resulted over the last decade was what Shah had envisaged back in 2008: A huge uptick in cheese consumption.

In 2019, Parag is the second-biggest cheese maker in India by value, according to industry estimates. With 35 percent of the value market share, its ‘Go’ cheese trails Amul, but is almost four times bigger than Britannia. Akshali now intends to “repeat history”. Protein will be the next cheese five years down the line. “Parag is getting a protein makeover,” she beams, adding that the company has also been expanding its footprint in North India. Last April, the acquisition of Danone’s dairy factory in Sonepat, Haryana, helped Parag strengthen the distribution of milk and milk products in NCR and Haryana.

Though the intention, and the plan, is to replicate cheese, the result might not be the same this time. Reason: Cheap imported protein brands that have flooded the market across India.

In a recent earnings calls, Shah underlined the strategy of his company to stay away from the B2B segment dominated by cheap imports. With the kind of investments and efforts the company has put in the protein business over the last four to five years, Shah pointed out it does not make sense to get into commodities and sell it against current players who are selling cheap.

The whey protein market, especially in the lower end—which constitutes around 80 percent—was a waste stream two years ago. Recently, companies have tried converting it into some dried form. It is a highly competitive B2B market and does not make any sense to get into it as of now, he maintained. “We are not targeting the lowest end of the market and we don’t want to get there,” he added.

The biggest edge, Shah claims, which Parag has over imported whey protein is the quality. “Avvatar is India’s first brand made from 100 percent cow milk-based protein which is manufactured at our plant,” he says. The consumers, Akshali adds, have accepted the product that tastes better than any international brand. “That’s why this has been a very fast moving product for us,” she claims.

But there is still much ground to cover in terms of consumer recall, visibility and brand building. Protein supplement market, especially in the sports segment in India, is still a commodity, driven by medical store owners. “Where is the brand?”

asks Saurabh Jindal, analyst at Bonanza Portfolio. Though their vast retail network might help in pushing their offerings, brand building through mass advertising is the need of the hour. “Building a brand out of a commodity is what will help them stand out in a cluttered market,” Jindal reckons.

Akshali believes the company has enough bandwidth to focus on all categories. As far as protein products are concerned, Parag is targeting the right segment of consumers through sampling at gyms and parks. Efforts are also being made to educate consumers about the merits of opting for protein made from cow milk. The opportunity, she adds, is massive and the potential for growth enormous. “Protein is the whey to go and grow,” she smiles.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)