Vivo's V-shaped comeback

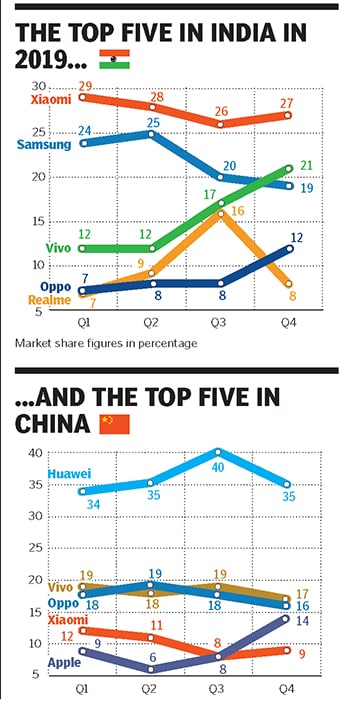

Vivo capped a splendid performance in 2019 by toppling Samsung to become No. 2 in the October to December quarter. Can the Chinese smartphone maker maintain its winning run once the Covid-19 dust settles down?

Vivo India is the second biggest after China. Over the next five years, our plan is to shift gears from a follower to a leader: Jerome Chen, CEO, Vivo India

Vivo India is the second biggest after China. Over the next five years, our plan is to shift gears from a follower to a leader: Jerome Chen, CEO, Vivo IndiaPhotomontage: Madhu Kapparath

Photos: Vivo & Shutterstock

Simple things, reckons Jerome Chen, are easy to understand, but quite difficult to do. It’s early March, Holi is just a few days away, and the only colour that’s visible across the satellite city of Gurugram is blue hoardings of Vivo smartphones on huge metro pillars.

Sitting in a café on the ground floor of the Palms Spring Plaza building, just 100 metres from Vivo Sector 53-54 metro station in Gurugram, Chen looks bemused. Every day scores of bikers and speeding cars miss the U-turn on the main road that goes towards Delhi. A huge signboard reading ‘Slow down for a U-turn’ falls on their blind spot. “They just need to see the sign and follow it. It’s that simple,” says Chen, irritation in his voice quite palpable. “Simple things,” reinforces the chief executive officer of Vivo India who came to the country in August 2014 to set up operations, “are difficult to do.”

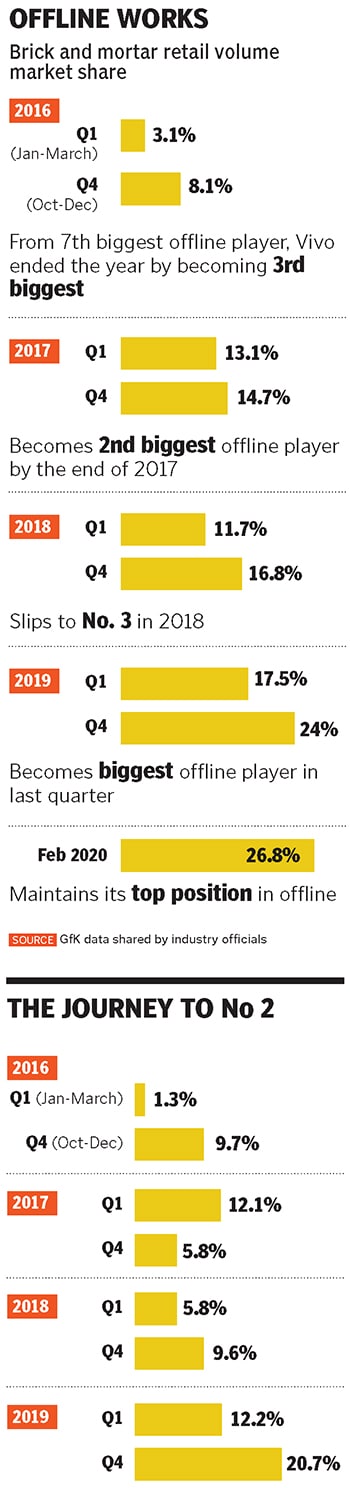

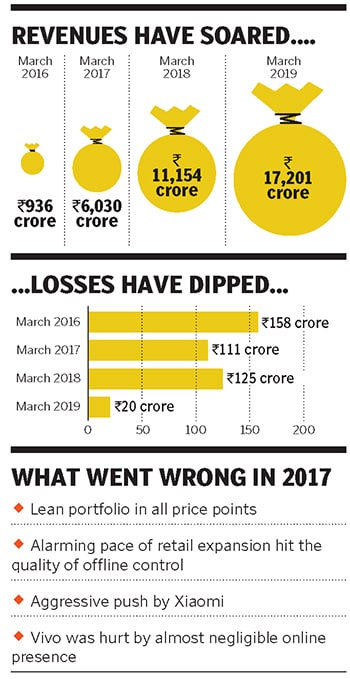

Three years back, towards the end of 2017, Chen too was guilty of oversight, and failing to do simple things. The writing was on the wall, but he couldn’t see it. For a company that swears by the philosophy of slow is fast, over-speeding was turning out to be dangerous. In just a year, market share had zoomed from 3.6 percent in the second quarter of 2016 to 12.6 percent a year later.

Then, for the next three quarters, the inevitable happened. Vivo dipped to a low of 5.8 percent in the first quarter (January-March) of 2018, its lowest ever. “We grew a bit too fast. But we wanted to go at a faster clip,” recalls Chen. “Kyon hua pata hai (I know why it happened),” he mutters. He’s picked up a few Hindi words during his five-year stint in India. During good times, he underlines, it’s all the more easy to forget simple things. The company, though, took a quick U-turn, and started doing simple things by sharply focusing on four key stakeholders: Customers, retailers, shareholders and employees.

The U-turn led to a V-shaped recovery. In the last quarter of 2019 (October-December), Vivo pipped South Korean rival Samsung to become the second biggest smartphone maker after Xiaomi. For a smartphone maker that shunned the online route taken by its rivals such as Xiaomi and opted for the traditional brick-and-mortar model to carve a place for itself, the success was even more satisfying. The second biggest player in India, which occupies the same ranking in its motherland behind Huawei, gets over 90 percent of revenues from offline sales.

Cut to mid-April. India is in the second spell of lockdown, Vivo Sector 53-54 Metro Station is shuttered and, although the roads are deserted, a few swanky cars and bikes can still be seen speeding on the empty stretches. “People just need to follow the simple rule of staying at home,” says Chen, who declined to step out for a photo shoot or meet for a follow-up interview. “Isn’t it simple? We just need to stay put wherever we are unless something urgent pops up,” he says. “Well, we can always talk over the phone, can’t we?” he says with a laugh.

SLOW IS FAST

For Vivo, the beginning was muted. For Chen, though, “slow was fast”. For any Chinese brand, entering India in 2014 was not difficult. The country had seen a bevy of brands from Dragon Land such as Gionee, and the Indian or desi clones such as Micromax and Lava who were assembling the handsets imported from China. Though entry was easy and simple, winning trust was difficult. “People,” recalls Chen, “perceived Chinese brands to be of low quality and cheap. Another damning perception was that the brands from China were in India to make money and run away.”

JC—that’s how Chen is addressed by his colleagues—decided to tackle the bigger challenge first: Battling perception and changing it. He, along with his team of loyal distributors who had come from China, fanned out across India to understand the need of the market. Along with making progress on the retail front, what helped Chen was a concurrent slide in market share of HTC, Sony and other Chinese brands. The offline retailers, consequently, had to try the new kid on the block. The brand spent the first month in India selling around 100 handsets every day.

What also helped in beefing up the credibility of the brand was nil consumer complaints. In the third month, the offtake increased to 1,000 handsets every day, and then there was no looking back. The company, till February this year, was selling an estimated 71,000 units per day.

Back in 2014, retailers lapped up the generous margin offered by Vivo—an estimated 13-15 percent, much more than the 7-8 percent offered by most other brands. The third factor that helped cement a strong retail footprint was a dedicated team to look into distribution. One person was put in charge of up to 20 shops as against the industry norm of 1:50 or 1:100.

Adding more heft to the offline strategy was appointing Vivo Brand Ambassadors (VBAs): Young marketing executives, sporting Vivo-branded tees, and placed inside the shops. They soon became the face of the brand, and the first point of interaction with the consumers. Trust was slowly built, and the retail footprint was painstakingly expanded. But something else also happened, which made the other brands sit up and take notice. Vivo institutionalised a decentralised form of structure. Every state in India was headed by a Chinese distributor who had come to India when Vivo entered in 2014. Every state ‘company’—as Chen describes it—was allowed to frame its respective distribution and marketing strategy, suited to that particular region. A sense of ownership in the company and skin in the game helped fuel the retail machine.

The army of retail distributors traces its origin to an existential crisis faced by BBK Electronics, the parent company of Vivo, Oppo, OnePlus and Realme, way back in 2012 in China. BBK, then into the business of feature phones, stared at a bleak future when the entire Chinese market overnight got hooked to smartphones as operators distributed handsets for free. Consumers were only asked to pay for data. “The change happened much faster than anybody’s expectation,” recalls Chen, who joined BBK in 2002.

Sitting on a huge stockpile of feature phones, which were twice as expensive as the newly-arrived smartphones, BBK was left with only one option: Liquidate the stock at a heavy discount. Retailers, along with the company, took a massive hit. But all stayed together. And when BBK entered into smartphones later on, all these retailers became an integral part of the company. “This is the culture of the organisation that helped it to survive the crisis,” contends Chen.

Vivo’s offline bet, reckon industry experts, was timely. In 2014, offline made up over 85 percent of the smartphone market. With a rapid decline in the fortunes of the Indian players, and a concurrent preference of all new players from China opting for online over offline, the brick-and-mortar distributors were left with only Samsung.

“The timing was right, and the market was ripe for Vivo,” says Tarun Pathak, associate director at Counterpoint Research. What also helped in standing out in a cluttered market was Vivo’s focus on music, even as everybody else was flaunting camera. “The gambit worked,” adds Pathak, adding that betting on offline distribution won the loyalty of the retailers who felt threatened by the online juggernaut. The icing on the cake, points out Pathak, was a lucrative retail margin offered by Vivo. Being ready with 4G handsets also proved to be a big blessing as the Indian ecosystem was fast moving away from 3G.

The brand, Pathak, underlines, also took a U-turn last year, in terms of coming up with a special series for online only: U series. Though the company decided to do away with the online-only product, the success of the U series made it realise the importance of having a hybrid approach in gaining market share.

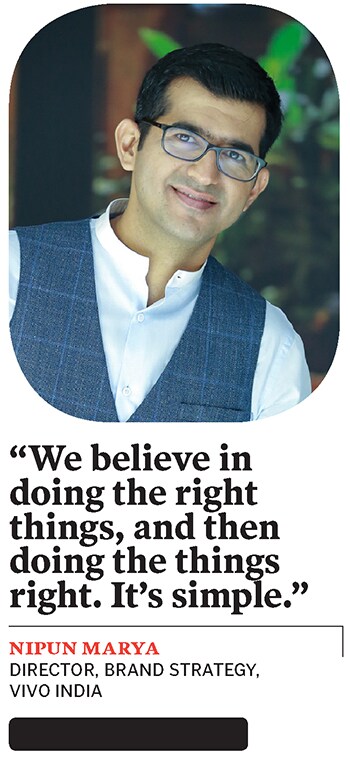

Nipun Marya, director of brand strategy of Vivo India, reckons that following the basics and slogging always helps. For any brand coming to India, online offers multiple advantages: No need for large infrastructure, one can bypass distributors, and a lean team will suffice. “You can just make a product and sell it online,” says Marya, who has had stints with Samsung and Lava before Vivo. In offline, he reckons, hard work is required. “That’s why Vivo is a labour of love for all of us,” he says, adding that the brand has a spread across 70,000 retailers and boasts of 30,000 VBAs.

Marketing experts reckon there is enough juice left in the offline model. When significant brands such as Xiaomi have reached pole position largely on the back of online, it takes some boldness to charter an offline path. “Vivo’s success, therefore, has a sweetness to it,” says Abraham Koshy, professor of marketing at IIM Ahmedabad. While consumers got a good “look and feel” of the brand, salesmanship of the retailers and VBAs worked in tandem to convert the sale, and add to consumer stickiness.

Aggressive marketing was capped by bagging the title sponsorship of the Indian Premier League, rooting for kabaddi—the second biggest sport in India after cricket—and roping in Aamir Khan as brand ambassador. “Speed or over-speed was the only thing that could have undone all the excellent work,” says Koshy, hinting at how the company slipped towards the end of 2017.

Back in Gurugram, JC points out what went wrong. The focus on market share meant that the retail footprint zoomed to over 1 lakh retailers and 60,000 VBAs. “This was not the right thing to do,” he admits. In the rural markets of Uttar Pradesh and Odisha, there were retailers selling only 30 units per month. “In some places even vegetable and shoe shops had Vivo branding,” recalls JC. All these hit the perception and value of the brand. “We realised we were doing it wrong. We were too eager to gain market share,” he rues.

There was another chink: A skewed product portfolio. Vivo focused more on higher priced products—over ₹20,000. The reason was wide consumer acceptance. When you launch a product, explains Marya, which is double the average selling price in the industry, and also gets a terrific response, it means more revenue. What the company failed to realise is that 80 percent of the smartphone market was below ₹15,000. “At that time, our low-end products were not as good as the top-end ones,” confesses Marya. The result was a steady slide in market share for over three consecutive quarters.

If the setback was striking, the comeback last year was astonishing. The retailer footprint was rationalised—it’s now at 70,000. The excessive VBA flab was shed—it now stands at 30,000, half of what it was during 2018. A renewed focus on the Y Series of handsets (those priced between ₹8,000 and ₹12,000) paid dividends.

A sustained omni-channel play with a presence across all mass price segments also aided in coming back into the game. Being an offline heavy brand, contends Navkendar Singh, research director at IDC India, it continued investments in the offline channel in the form of incentives, attractive margins and timely settlements of schemes, which helped maintain positive sentiment across the channel’s width and depth. Additionally, it also made a foray into the online channel, with the Z and U series. “These were aggressively priced with high-end specifications and found encouraging response from online buyers,” says Singh, who quickly adds a word of caution. Though Covid-19 is going to impact all brands, what might become more challenging for Vivo is an equally aggressive play by online-heavy brands such as Xiaomi and Realme in their offline push. “The competition in brick and mortar will intensify,” he warns.

JC, on his part, believes in keeping things simple. “We will keep doing the right things, and in the right way,” he says, explaining his approach. Since the lockdown the company has been conducting extensive online training of its VBAs. “I don’t care about being number 1, 2 or 3,” he adds. What matters most now, he underscores, is satisfaction of four stakeholders: Consumers, retailers, shareholders and employees. “It can’t be one at the cost of another,” he says.

When asked if the company has enough ammunition to survive the Covid-19 crisis, JC keeps his response simple. He smiles ear to ear, in the shape of a U, and flashes a V sign on a Zoom call. Whether we are in China or India, he asserts, it’s time to have a strong belief that we can overcome this crisis together.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)