Cow to consumer: Beyond profit for Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation

At the Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation, which runs the Amul brand of dairy products, making profits is important only so that they can be routed back to the cattle farmers

Forbes India Leadership Award: Conscious Capitalist for the Year

Bhanubhai Patel from Sandesar village of Gujarat’s Kheda district wakes up at 5 am every day, recites the morning prayers and heads to his cattle farm. He affectionately pats his cows before milking them. Then, with the milk carefully packed in steel canisters, he heads to the Sandesar Dairy Cooperative Society—an institution he helped build along with others in his village, and one that has played a key role in establishing one of India’s most trusted brands: Amul.

GCMMF, which is headquartered in the nation’s milk city of Anand in Gujarat, had an annual turnover of Rs 20,733 crore in FY15, a remarkable 159 percent growth from just five years ago when it clocked Rs 8,005 crore.

But beyond the growth, the story of Amul is primarily one of grit, gumption and ambition of the cattle-rearing farmers of the Kheda region. In 1946, the farmers united to fight against corrupt middlemen who procured milk at arbitrary prices on behalf of the local Polson dairy. The middlemen would keep fat margins for themselves. Inspired by social leader Sardar Vallabhai Patel, the farmers decided to stop supplying milk to the local dairy: They rallied under the leadership of Tribhuvandas Patel, a local farmer, demanding their own cooperative society. After more than 15 days of complete shutdown, the British government relented and allowed the farmers to form a village dairy cooperative society. The British assumed the farmers would never be able to run it professionally and that the society would disband in a few months, if not weeks. But that was not to be.

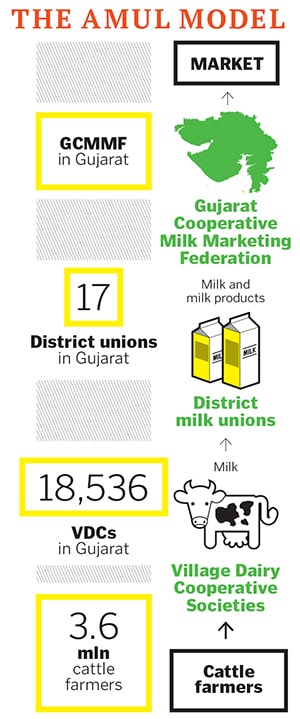

The first village dairy cooperative society was formed in 1946; there are over 18,500 such societies in Gujarat today. And it has inspired over 1.5 lakh such societies of other milk federations across the nation. This has led to the launch of multiple dairy cooperative movements across the length and breadth of India. Famously known as the Amul pattern, the three-tier structure of GCMMF has been replicated in various states via Operation Flood, executed by its architect, the late Dr Verghese Kurien, and it has turned India into the world’s largest milk producer.

Each farmer in the village dairy cooperative owns one share in his or her local society, which in turn owns a share in the District Milk Cooperative Union. Seventeen such unions own a share each in the apex body GCMMF that has 58 dairy plants and a milk handling capacity of 24 million litres per day.

This unique structure makes GCMMF possibly the only organisation that is built by farmers, run by farmers and works primarily for the interest of farmers. The company’s managing director RS Sodhi explains that for a company in the dairy sector, its CEO has only one goal—buy raw material (milk) at the lowest possible price and sell goods at the highest possible price so as to maximise profit margins. “But as the head of GCMMF, my goal is to buy raw material at a high price from the farmers, and then sell the final product at the highest quality and the lowest possible price,” says Sodhi. “So in a way, my role is diagonally opposite to that of other CEOs. As an intermediary, our role at GCMMF is to minimise our own profit, and ensure that both the milk supplier’s and the customer’s interests are protected and they repose trust in us.”

Moreover, GCMMF is bound by a mandate to buy all the milk that farmers bring to them, unlike other private dairies that procure only the required amount. As a result, GCMMF has to operate on a much larger scale and keep prices low so that whatever it produces is sold quickly.

GCMMF’s business strategy can be summed up in two points: One, value for many; two, value for money. The company has a mandate to pay the highest possible price for milk supplied by the millions of farmers, who are also its owners. But at the same time, it also needs to ensure that the products it sells always carry the ‘value for money’ perception by its consumers without compromising on quality standards. It’s a tightrope walk.

GCMMF was instituted in 1973 as a sales and marketing organisation by the then six district milk cooperative unions with an agenda to manage brand Amul and scale its operations across the nation. With professionals hired from the best management institutes in the country, the company has established brand Amul not just in India but also in the Middle East, Southeast Asia, the US and even Australia and New Zealand. It recently set up a plant in New Jersey in the US to manufacture ghee, shrikhand and paneer (cottage cheese), products coveted by the Indian diaspora.

Every village dairy cooperative society that is core to GCMMF is a distinct financial entity with its own balance sheet and has a committee that works in an honorary capacity. Each society hires a team comprising an accountant, a milk collector, a milk tester and an administrator who runs the centre. Expenses for these are borne by the society as it earns anywhere between 2 and 4 percent margins on every litre of milk sold to the district union which, in turn, it sells to GCMMF. The district union collects milk, processes it into value-added products like cheese, butter, ghee and chocolates, while the federation (GCMMF) ensures quality checks over and above the ones performed at the district unions’ factories. GCMMF also tells the district unions what to produce on the basis of its demand and supply study. Without the quality certification of the federation, no product is released in the market.

Automation and technology deployment at each dairy cooperative society has enabled instant calculation of fat content in the milk deposited by farmers, and thereby the price due to them. Profit is made at all levels in the three-tier structure, right up to the apex body GCMMF. The profits are then routed back to the farmers via the village cooperatives, which also provide various other services such as cattle care, artificial insemination, cattle feed, veterinary support, etc. “The farmer gets a pre-determined price for milk per litre when he or she brings it to the village cooperative. This is the first tranche of payment,” explains Sodhi. “But at the end of the financial year, after profits are tabulated, a large portion of the gains are distributed back to the farmers by increasing the per litre price of milk that was procured from them. The profits thus return to the farmer, in a second tranche, as ‘price difference’. Hence, farmers who bring in more milk stand to benefit the most.” In the last two years, on an average, the price of procured milk has been revised upwards by 24 percent after profits are tabulated.

“Making profits is not our motive, since we do not distribute dividends to our shareholders [the farmers],” adds Sodhi. This also helps avoid any tax that would be levied on the shareholders if GCMMF were to distribute profits among farmers. Since a major portion of the profit is routed back to the farmer, GCMMF keeps only a nominal profit for itself, rendering its tax outgo very low. It sends its profit as surplus to the district unions which add their own profit to it before passing it to the village dairy cooperatives, who do the same and send it forward. The final amount determines the price increase given to the farmers. This has been the practice at all milk cooperatives in the country for the last six decades.

Throughout the chain, ownership of each tier is with the farmers. And together with professionals, they ensure procurement, processing and marketing of fresh milk and dairy products. Many dairy cooperatives, even in developed economies, don’t handle all these three functions. They would rather sell the milk or milk powder to larger dairy companies, or FMCG firms, as handling sales and marketing or production of milk, a perishable commodity, is quite challenging. But farmers at GCMMF know that the biggest chunk of profits lie in selling value-added products of milk and not just fresh milk.

Sodhi says the world over, farmers get only about 30 percent of the price of the final milk product. At GCMMF, they get up to 80 percent value back since it has chosen the difficult path of creating value-added products on its own and selling them too.

GCMMF currently handles only 4-5 percent of the milk production in India, which is about 25 percent of the milk in the organised sector. Since only 20 percent of the dairy business in India is organised, there is immense scope for growth in the milk and dairy business alone. Hence, the company plans to expand its milk procurement and distribution into the untapped regions of the nation. It stepped out of Gujarat to start sale of fresh milk in 2004 in Delhi and has entered six more states since then.

“Even at the current pace of growth, there is still a lot of room for growth. We are not under any threat from private producers,” says Sodhi. And he believes the sector will grow if a private player enters the fray. “First of all, the farmers will benefit since their milk will be in demand and more of the unorganised sector will become organised. So we will be more than happy about competition. That’s the difference between us and the private sector, we welcome competition.”

This is what makes GCMMF a ‘conscious capitalist’. Its core objective is to ensure greater good for India’s cattle farmers than protect its profit margins. It is for this reason that Dr Kurien helped set up the National Dairy Development Board to replicate the Amul pattern across India, resulting in 23 state milk marketing federations, like GCMMF, that now compete with each other with their own branded products; all of it leads to a higher price for the cattle-rearing farmer.

GCMMF’s conscious capitalism extends to the consumer too as the company is careful not to overprice its customers. “Although Amul products, especially butter, are always in high demand, we do not exploit our monopoly. Even during shortages, we have never increased prices. We believe that you have to be responsible and relevant to society,” says Kishore Jhala, chief general manager, GCMMF.

Though it has the potential to extend the Amul brand to various other product categories and services and become a multi-billion dollar company, GCMMF does not plan to deviate from its singular goal of ramping up business around milk and milk products. Its owners (farmers) are not interested in taking the turnover to Rs 1 lakh crore by entering new businesses; they would rather increase milk procurement and raise the price they are paid for their milk.

Even when it comes to advertising spends, GCMMF is prudent. On an average, an FMCG company spends 8-14 percent of its sales turnover on advertising. Dr Kurien realised early that brand building is vital to establish the Amul brand, but he wanted to adopt an innovative and low-cost approach. He opted for the billboard campaign for Amul butter that began in 1966 and it continues to date with witty remarks on current affairs. Since then, as a principle, the company spends less than 1 percent of its sales on advertising; last year it spent 0.8 percent. But consistency has been the key and it has always chosen to amplify the Amul brand name than advertise its product lines. It has bought 80 billboard sites nationally, but the moment a new campaign hits, it goes viral on digital media.

The company has given complete freedom to its advertising agency, daCunha Communications as the billboard campaign requires no approval from the GCMMF team. They trust the agency implicitly, it says.

Instead, it prefers to focus on milk procurement and sales than brand promotion because they know every extra minute spent on their core task will result in higher milk prices for their owners, among them, farmer Bhanubhai Patel.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)