For Rajasthan Patrika, it is Readers Above Advertisers

Rajasthan Patrika is an unabashedly family-run newspaper and the promoters, the Kotharis, believe their business cannot work in any other way

What was born in 1956 as a quarter-sized eveninger—started by Karpoor Chandra Kulish with Rs 500 borrowed from a friend and just “two-and-a-half people”

as staff—has grown up. It is now a reputed Hindi daily, spread across eight states, spanning 34 cities with over 250 editions. That is how far Rajasthan Patrika has come, both in size as well as geographically. Not only is it present in most states of the Hindi heartland but also in non-Hindi states like Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat and West Bengal. Officially known as Patrika in most regions, much of the newspaper’s growth has taken place in the last decade after it was woken up from slumber by Dainik Bhaskar (DB) which entered the former’s bastion of Rajasthan in 1995-96.

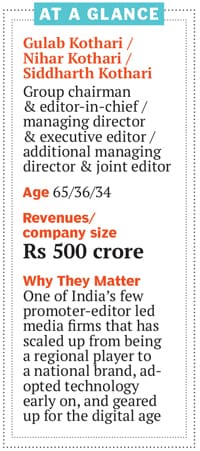

Patrika had started to feel like a sleeping giant, admits Nihar Kothari, Kulish’s grandson, who now manages the newspaper’s editorial policies; his brother Siddharth heads the advertising and marketing departments. Their father Gulab Kothari is editor-in-chief of the paper, and an author of many books.

“Until Dainik Bhaskar came, we were moving along at our own pace, happy doing what was required,” Nihar says. They had scaled up extensively in Rajasthan with local editions in different cities, and had also entered two states in the south. In retrospect, DB’s entry into Jaipur, the headquarters of the Patrika, proved invaluable, he points out. “Competition did to us what Hyundai did to Maruti—its growth just catapulted. We realised our true brand value, put in the required effort to scale up and grew substantially.”

The change of guard at the top also made a significant difference. Till about 2003, founding editor Kulish and his two sons (Milap and Gulab) were at the vanguard, testing different markets and penetrating deeper into Rajasthan. They had already made headway in Gujarat, West Bengal, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu. Then, in 2003-04, Gulab’s sons, Nihar and Siddharth, joined the family business; that gave the Patrika Group a much-needed momentum.

Gulab turned 60 in 2009, and in an editorial in the paper, announced his retirement from the day-to-day handling of the business. However, he continues to write editorials in Patrika.

Nihar and Siddharth are now in charge. And they have relentlessly pursued growth, introducing the latest technology, and expanding the business through new ventures such as radio stations, an outdoor advertising division, and event management; they have also taken the newspaper to states like Madhya Pradesh and Chattisgarh.

The journey hasn’t been easy though, father and sons tell Forbes India during an interview at Jaipur’s Kesargarh fort, the headquarters of the newspaper. They have faced many upheavals and financial troubles, with state-sponsored advertising running dry whenever they wrote against local state governments, or getting singed in competitive battles with other newspapers on entering new territories.

The Values Business

The reader should come first: That is the only mission statement that Kulish, who passed away in 2006, gave his son Gulab; he, in turn, has made the reader the focus of his editorial policy.

Consider how often Patrika takes up civic issues in the interest of the reader; be it illegal changes in development plans or inept bureaucracy that compromises citizen safety. From picking up battles with telecom players (one of the biggest category of advertisers for newspapers) on tower radiation to pushing the agenda of oil exploration and discovery in Rajasthan’s Barmer district, the Patrika Group has often forsaken financial gain at the altar of honest and accurate reportage.

“For three years, we lost advertising from the telecom sector when we ran a huge campaign on tower radiation and its potential for causing cancer. But we persisted. Because that’s the core philosophy of this paper and it cannot be compromised at any cost,” says Siddharth, who is now battle-scarred in the turbulent quest to maintain the editorial integrity of the paper vis-à-vis protecting advertiser interest. “Money will come in the long term, but integrity and credibility cannot be wasted on short-term financial goals,” says Gulab. “Beyond a point, all the extra money you earn is merely adding to your bank balance. Respect is the biggest asset you can gather in this lifetime. And that is most important for us Marwaris.”

Nihar, the elder son, adds: “In this line of business you can be either respected or resourceful [rich]. We don’t need to reach the top right now. If it takes time, we are ready to wait.”

At this point, the family reminds you why Rajasthan Patrika was started way back in the 1950s. Karpoor Chandra Kulish was a reporter in a local newspaper then and was exasperated with the political affiliations publications had in the state. He felt the need for an independent paper that would be the voice of the common man. Today, Kulish would have been pleased to see his progeny attempting to uphold his values amidst political as well as corporate (and advertiser) pressures on the group.

Of particular pride to Patrika is an initiative launched during the 2009 state elections. Through it, the newspaper invited its readers from across constituencies to come together and create a manifesto for every local politician. The suggestions were collated in a document and handed over to the candidates personally. Subsequently, the army of reporters at Patrika monitored the candidate’s steps, reminding him of the manifesto given to him by the electorate and about the tasks yet unfinished. This programme met with great success in 2013, and made a significant difference to the polity of Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh; it also won the Patrika Group a National Media Award and recognition by the Election Commission of India for raising voter awareness.

But there are some question marks still on this apparently well-intentioned media entity. Rajasthan Patrika and its owners have been alleged of being close to a particular chief minister from 1970-80. However, the paper has been working assiduously over the last decade to move away from these associations, and to change public perception.

Family First

Although Patrika has always had professionals in senior positions, some of them even running editorial operations, Gulab Kothari and his sons maintain firm control.

They aren’t handing over the reins to a non-family member or an external CEO anytime soon. This move, they believe, will be counterproductive.

A true Marwari businessman, Gulab says, does not believe in FDI or in listing his company on the stock exchange. “What is the need to get an outsider in the family business? And why should we imitate others or satisfy our ego in the name of growth or in an attempt to be number one immediately?” he asks. “If you borrow money for growth, I believe you can’t reverse that decision. The question is, do I give my children 100 percent of the business or leave them to deal with an outsider who I sold a stake to? My view is, expand less and gradually… we don’t need to jump the gun by taking debt.”

Nihar, meanwhile, says that a professional CEO can’t take the risks a media business requires. “It’s not his fault but, by design, his mandate is to protect rather than take big risks. At times, this business needs one to take audacious bets, put the last penny at stake, which a CEO will never be able to do,” he says. “A CEO can be a great business guy, but what if the promoter or shareholder wants to destroy some money now for a future larger goal? He can’t take that call. Our presence is critical… and that’s why you see families coming back to the media business now,” he adds.

(This story appears in the 30 November, -0001 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)