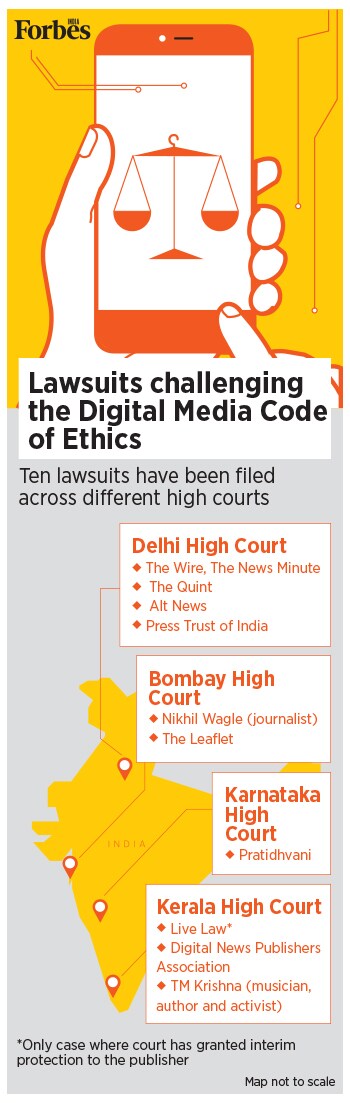

PTI sues Centre, calls digital media code state's 'weapon' to control media

India's largest news agency has become the tenth party to challenge the rules, but the Delhi HC refused to grant interim protection to any publisher

Image: Shutterstock

Image: Shutterstock

The largest news agency in the country, the Press Trust of India (PTI), has challenged the constitutional validity of Part III of the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and

Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021, which seek to oversee regulation of digital news media publishers. PTI has argued that the Code of Ethics is “draconian” and that the Rules “usher in an era of surveillance and fear”, which will result in “self-censorship” and violation of fundamental rights.

It has also stated that Part II of the Rules, which govern intermediaries, are “antithetical to fundamental rights”. Arguing that they should be stayed, PTI has said the Rules are only meant to be “a weapon for the Executive or the State to enter and directly control the content of online digital news portal”. Filed on behalf of PTI’s Chief Administrative Officer Mohini Ranjan Mishra, the lawsuit echoes other similar lawsuits as it calls out “vague conditions” such as “good taste”, “decency”, prohibition of “half-truths” mentioned in the Code of Ethics.

Although PTI’s petition has been filed by Mishra, it makes it clear that its editor-in-chief and CEO, Vijay Joshi, is involved in the matter.

The petition clarifies that it is challenging the Rules only as far as they apply to news publishers, and not to OTT platforms or intermediaries.

Forbes India

Forbes India