Facebook, WhatsApp sue Indian government over traceability requirement

In two separate petitions filed in the Delhi High Court, Facebook and WhatsApp have challenged the traceability requirement in the Intermediary Rules, and asked the court not to impose criminal liability if traceability is not implemented. Forbes India, after reviewing the petitions, summarises the arguments made

The heart of the matter are WhatsApp’s entire default service and Facebook’s specific “Secret Conversations” feature on Messenger that allows users to opt-in for end-to-end encrypted messaging; Image: Shutterstock

The heart of the matter are WhatsApp’s entire default service and Facebook’s specific “Secret Conversations” feature on Messenger that allows users to opt-in for end-to-end encrypted messaging; Image: Shutterstock

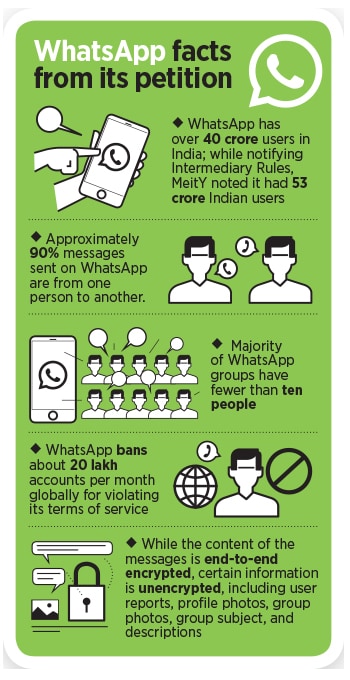

WhatsApp and its parent company Facebook are finally going on the offensive to protect end-to-end encryption. In two separate petitions filed with the Delhi High Court on the night of May 25, the two companies argued that the traceability requirement—mandated under the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021, notified in February 2021—will force them to break end-to-end encryption. They have also called the traceability requirement unconstitutional and violative of people’s right to privacy, as guaranteed under the Supreme Court’s Puttaswamy judgement.

The two social media giants want the Delhi High Court to declare the traceability requirement as ultra vires (beyond the legal mandate of) the Information Technology Act, 2000, and that no criminal liability should be imposed if the companies do not implement traceability. At the heart of the matter is WhatsApp’s entire default service and Facebook’s specific “Secret Conversations” feature on Messenger that allows users to opt-in for end-to-end encrypted messaging.

In a no-holds barred blog post, WhatsApp called traceability “ineffective and highly susceptible to abuse”, which would effectively mandate “a new form of mass surveillance” explaining that to trace even one message, WhatsApp would have to trace every message and will thus land up with “giant databases” with “permanent identity stamp[s]” of every message that is sent on its platform. This echoes Forbes India’s previous reporting wherein experts had warned that retaining digital fingerprints of messages (read: hashes) would lead to the creation of giant catalogues through which WhatsApp will be able to track all the messages that people send on its platform.

In response to the lawsuits, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) issued a statement that the traceability requirement passes the muster of proportionality. “It is in public interest that who started the mischief leading to such crime must be detected and punished,” the statement read.

The petitions have thus far not been listed for hearing in the Delhi High Court but it is expected that they will be heard by the division bench led by Chief Justice D.N. Patel, who is also hearing three separate cases against WhatsApp’s 2021 Privacy Policy update.