Ajay Mariwala 2.0: Spicing it up with a secret sauce

A seasoned F&B founder has been inconspicuously garnishing his second innings with a unique recipe, a new play and a vast user base, which is largely under-serviced. Can Ajay Mariwala's gravy train at Food Service India reach a different and desired destination this time?

Ajay Mariwala, Founder of Food Service India

Image: Mexy Xavier

Ajay Mariwala, Founder of Food Service India

Image: Mexy Xavier

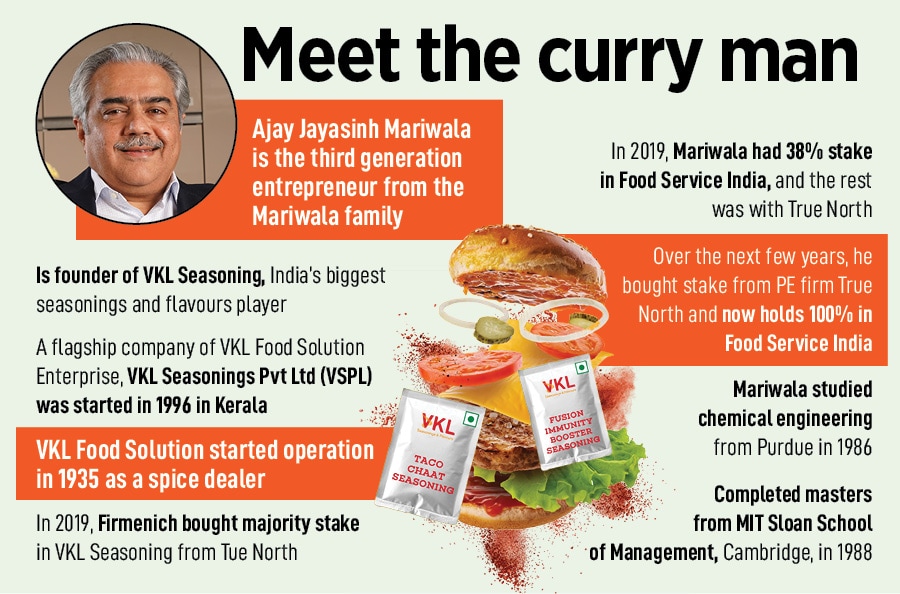

Kochi, Kerala, 2015. There was an unusual flavour in the monthly accounts book. And the seasoned entrepreneur was quick to spot the odd condiment. “There was a rogue sales guy in South India,” recalls Ajay Mariwala, who founded VKL Seasoning—India's biggest seasonings and flavours’ company, which reportedly had Yum! India, Domino’s Pizza, McDonalds India and Burger King among its QSR clients—in 1996.

During one of his monthly rituals of scanning the ledger in early 2015, the third-generation entrepreneur detected a bunch of random local ‘distributors’ in Salem, Bengaluru and Chennai, and quickly summoned the sales guy concerned. “What is wrong with you?” asked the founder of the food ingredients’ company in which private equity (PE) major True North (which was then known as India Value Fund Advisors) had invested $40 million in 2013. “Don’t you know we don’t sell our stuff to distributors,” he reprimanded his staff, who stayed mum. “We deal with India’s best food brands. And you are selling to unknown guys,” Mariwala was in no mood to cut him some slack. “Don’t do this again,” he warned the errant employee.

Two months later, the same employee turned out to be a habitual offender. “You have done it again,” fumed Mariwala. “What is going on? Why are you selling to such people,” he asked, issuing a final warning. A few months later, the founder lost his cool. “I have had enough. Either you explain what is going on or you are out,” bristled Mariwala. “Sir,” the accused staff meekly replied, “you need to come with me to understand what is going on.”

Back in the US in 1988, it was not hard for a young Mariwala to understand what was going on in America. “The trucks were all over the place,” recalls Mariwala, who studied chemical engineering from Purdue University in 1986, and was pursuing a masters degree from MIT Sloan School of Management. “They were omnipresent,” recounts the founder who was intrigued as well as impressed with the way Sysco’s army of trucks dotted the American retail landscape and highways. American biggie Sysco is the world’s biggest food service company selling, marketing and distributing food and non-food products to restaurants, health care and educational establishments. “We used to get Sysco’s supplies in the dorms in the US,” he says.

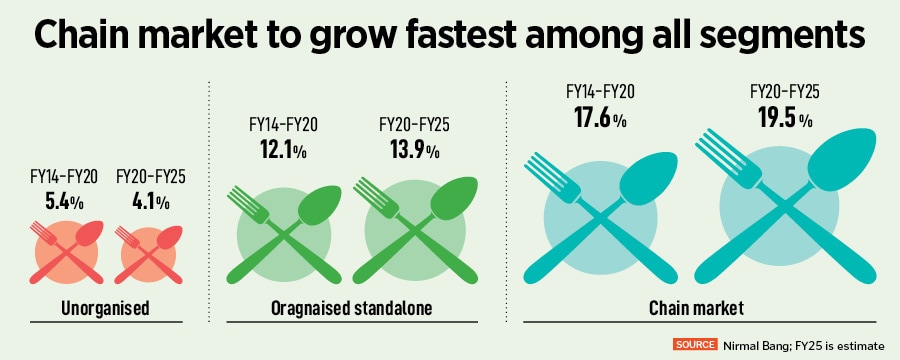

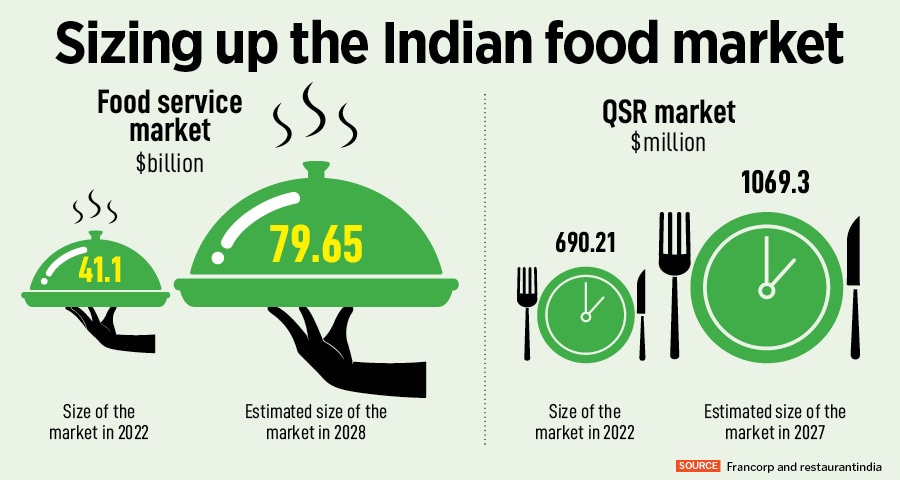

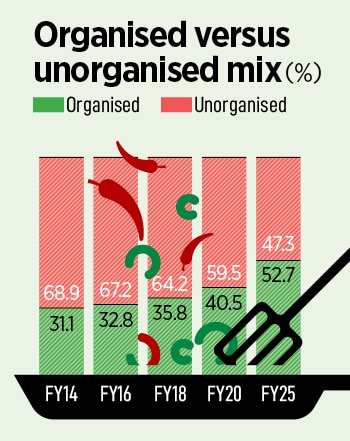

Mariwala, though, reckons that the beginning of the golden period of India’s food industry is still at least four to five years away. “We need a little bit more network effect,” he says, alluding to an uptick in economic performance of states like Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, Odisha and West Bengal. With an explosion of the middle class and rise in income levels, food service will see a widening of the market and opportunity.

Mariwala, though, reckons that the beginning of the golden period of India’s food industry is still at least four to five years away. “We need a little bit more network effect,” he says, alluding to an uptick in economic performance of states like Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, Odisha and West Bengal. With an explosion of the middle class and rise in income levels, food service will see a widening of the market and opportunity.