Ather Energy has survived so far by scripting a differentiated play. Can they continue creating magic?

A couple of close calls, moments of self-doubt, a handful of daring rescues and a firm belief in magic. Tarun Mehta and Swapnil Jain have had a thrilling ride so far with their electric vehicle startup

Tarun Mehta, Co-founder and CEO of Ather Energy Image: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India

Tarun Mehta, Co-founder and CEO of Ather Energy Image: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India

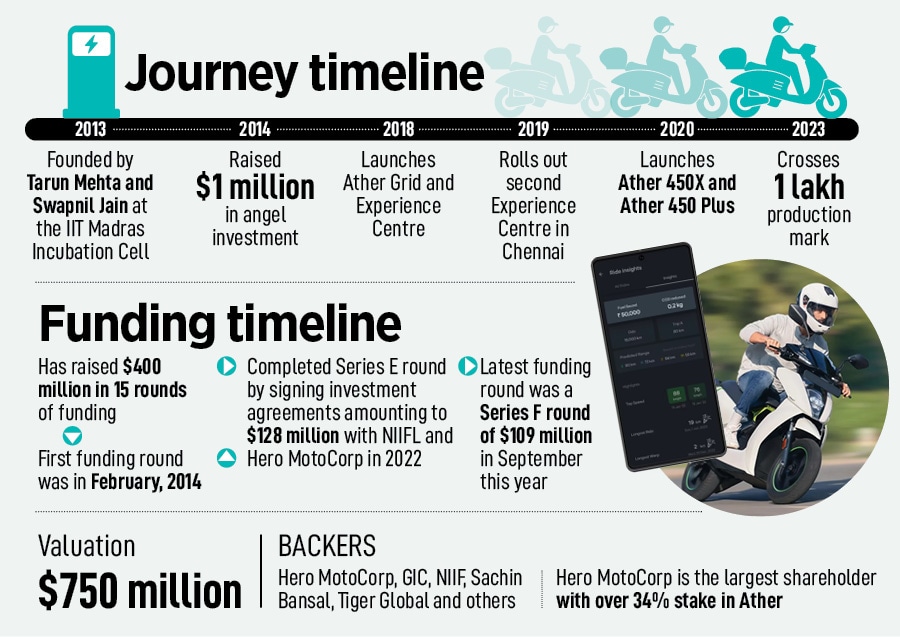

October 2014, Bengaluru. Eleven months, maiden venture, and the rookies ran out of money. It was an existential crisis for Tarun Mehta and Swapnil Jain. The batch mates from IIT Madras had made a daring move by starting two-wheeler EV venture Ather Energy in October 2013. “It was bonkers,” recalls Mehta. Two young boys—first-generation entrepreneurs with no money, no connects and no storied family background in business—were engineering an electrifying story that not many in the country had ever dared to dream. The greenhorns had made an audacious pitch of building a two-wheeler EV company. The vision was to invest a lot of money in research and development. “We wanted to build the largest R&D based two-wheeler EV company in the world,” says Mehta.

Ironically, the dream of the young guns was a nightmare for the potential backers. Everybody greeted them with disbelief and skepticism. Eleven months of hustle, and Ather ran of money in September of 2014. The duo dragged the venture into the next month, October, on the back of some personal loans. “We had decided to close down in November,” recounts Mehta, who had countless futile meetings with all kinds of investors. But in the dying moments, the founders spotted a spark of light.

Mehta had been in touch with a group of HNIs (high net-worth individuals), who evinced interest. The meeting was in Bengaluru. Mehta came from Chennai, and Ather was set for a new lease of life.

The meeting turned out to be a dud. They eventually called to inform that they would not invest. Mehta’s last hope had vanished into thin air. But just as death seemed evident, he had a fleeting thought. “Why don’t I drop a quick message to Sachin,” Mehta thought, referring to Sachin Bansal of Flipkart. A few months ago. Mehta had sent cold mails to a bunch of founders in the hope of some connects with potential investors. Only two replied, Bansal was one of them, and he had liked the vision of the young boys. “So I thought of going back to Sachin,” Mehta recalls. “He was my last shot.”