Delivery is on: Can Pizza Hut grab a bigger slice?

Twenty-five years in India and the world's biggest pizza player is still a distant No 2 to Domino's. Can Pizza Hut's latest brand positioning—Dil khol ke delivering—help it deliver a sucker punch?

Twenty-five years after entering India, Pizza Hut is now kneading new pizza dough in an attempt to reflect a new reality: It can deliver! Recently, it rolled out a campaign—Dil khol ke delivering—which underlines the message that the brand not only excels in delivery of pizzas, but also delivers on a bunch of other metrics such as taste, value, customer service and offers

Twenty-five years after entering India, Pizza Hut is now kneading new pizza dough in an attempt to reflect a new reality: It can deliver! Recently, it rolled out a campaign—Dil khol ke delivering—which underlines the message that the brand not only excels in delivery of pizzas, but also delivers on a bunch of other metrics such as taste, value, customer service and offers

Image: Amit Verma

It all started with vanity, sanity and reality. In June 1996, Pizza Hut was opening its first store in Bengaluru. And there was an element of vanity for the world’s biggest pizza brand. It was making its India debut ahead of rival Domino’s, which too set shop in the country in the same year. Being the first one, and having the first-mover advantage by a few days and months, helped Pizza Hut score brownie points, and make some extra cheese.

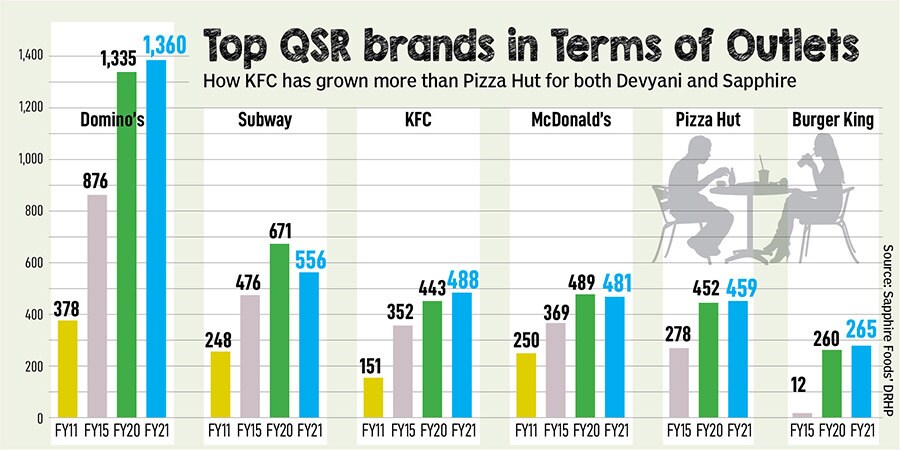

Back in 1996, starting as a dine-in restaurant—the DNA of Pizza Hut—ensured sanity in business. Indians was warming up to the concept of quick service restaurants (QSRs); burger giant McDonald’s had entered the country a year before, and so did rival KFC; and the lavish in-store food experience offered by the global biggies whetted the appetite of the consumers. Almost every QSR player sharply focussed on dine-in, and it made sense. This was the reality of the QSR industry then. The brand positioning was clear: While Pizza Hut had its perfect mojo in dine-in, rival Domino’s found nirvana in delivery.

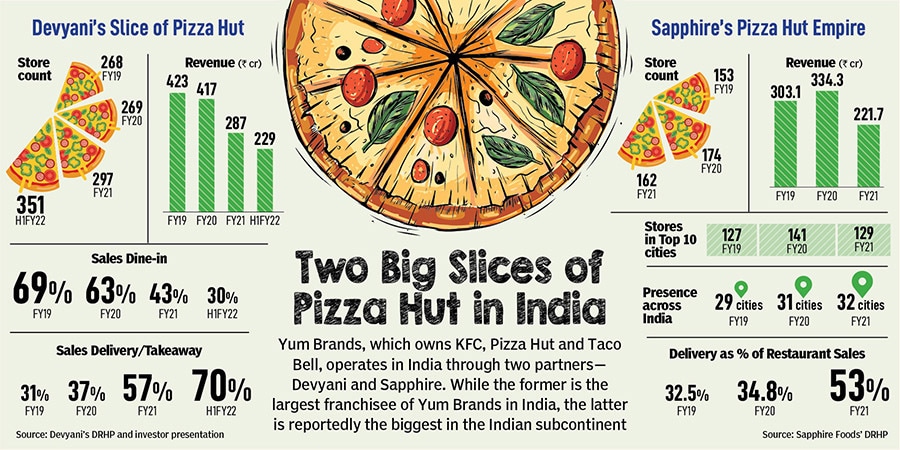

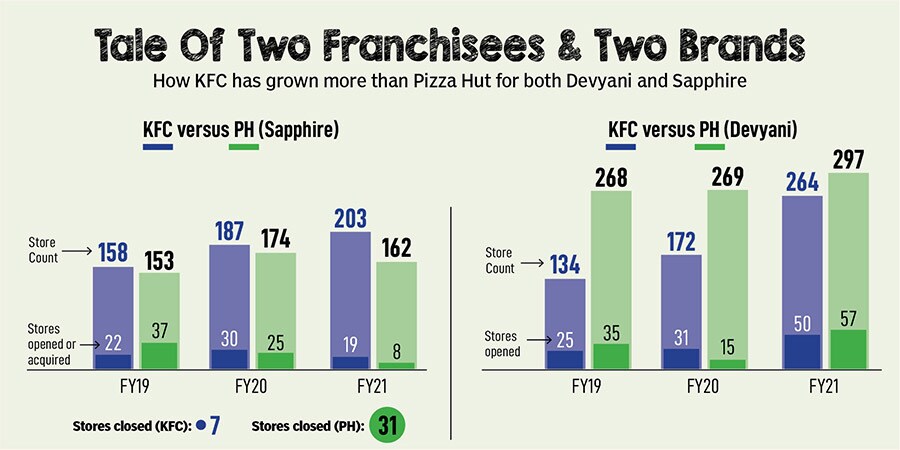

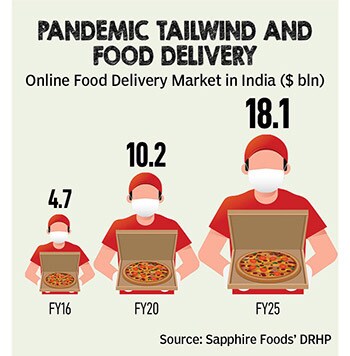

Cut to 2021, the world’s biggest pizza brand is confronted with a new set of vanity, sanity and reality. Pizza Hut is a distant number two in India, and wearing the badge of the biggest in the globe doesn’t add to its vanity. Dine-in has taken a brutal knock, thanks in large measure to Covid, and delivery has ushered in sanity for all rattled players scrambling for business. The ground reality too has changed. Domino’s is not only the biggest player but has also become synonymous with delivery.

Getting rid of the millstone makes sense. Reason: Pizza Hut had donned a new avatar. In fact, even before the onset of

Getting rid of the millstone makes sense. Reason: Pizza Hut had donned a new avatar. In fact, even before the onset of  The second big change happened on the delivery front. The brand started taking the format seriously.

The second big change happened on the delivery front. The brand started taking the format seriously.

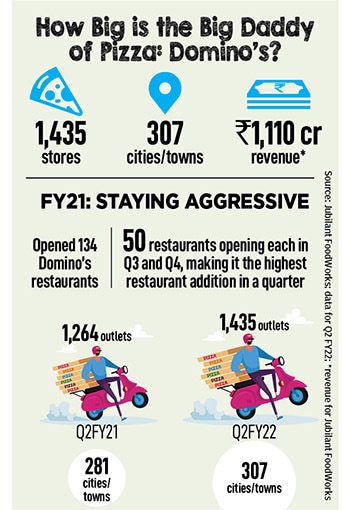

The third reality, reckon marketing experts, explains why Domino’s managed to grow at a furious pace in India and forced Pizza Hut to perpetually play a catch-up game. “The silver bullet is focus,” says Ashita Aggarwal, marketing professor at Bhavan’s SP Jain Institute of Management and Research in Mumbai. She explains. In 1996, Domino’s entered India by inking an exclusive master franchisee agreement with Jubilant FoodWorks. For the next 15 years, Jubilant didn’t have any other brand to manage. “They didn’t have an option but to grow big with Domino’s,” she says. “It was a do or die.”

The third reality, reckon marketing experts, explains why Domino’s managed to grow at a furious pace in India and forced Pizza Hut to perpetually play a catch-up game. “The silver bullet is focus,” says Ashita Aggarwal, marketing professor at Bhavan’s SP Jain Institute of Management and Research in Mumbai. She explains. In 1996, Domino’s entered India by inking an exclusive master franchisee agreement with Jubilant FoodWorks. For the next 15 years, Jubilant didn’t have any other brand to manage. “They didn’t have an option but to grow big with Domino’s,” she says. “It was a do or die.”