Finance Minister has big reform plans through bank privatisation. But are PSBs ready?

Big ticket reforms through privatisation of banks and insurance companies were announced during the Budget, but Covid-19 has played spoilsport with profitability, productivity, asset quality and financial management at the public sector banks

Employees of various government banks hold a banner as they shout slogans during a protest against the Privatization of Public Sector Banks and retrograde banking reforms during a two-day Nationwide strike at Jantar Mantar road on March 16, 2021 in New Delhi, India. Photo by Mehta/Hindustan Times via Getty Images

Employees of various government banks hold a banner as they shout slogans during a protest against the Privatization of Public Sector Banks and retrograde banking reforms during a two-day Nationwide strike at Jantar Mantar road on March 16, 2021 in New Delhi, India. Photo by Mehta/Hindustan Times via Getty Images

Four months after Minister of Finance Nirmala Sitharaman announced big steps to reform—through privatisation in the banking and insurance sectors—in this fiscal year’s budget, some real concerns are starting to play out. The murmurs over which public sector banks (PSBs) will be privatised have been growing since the government think-tank Niti Aayog, in June, shortlisted the names of two banks and recommended them to the Core Group of Secretaries on Disinvestment.

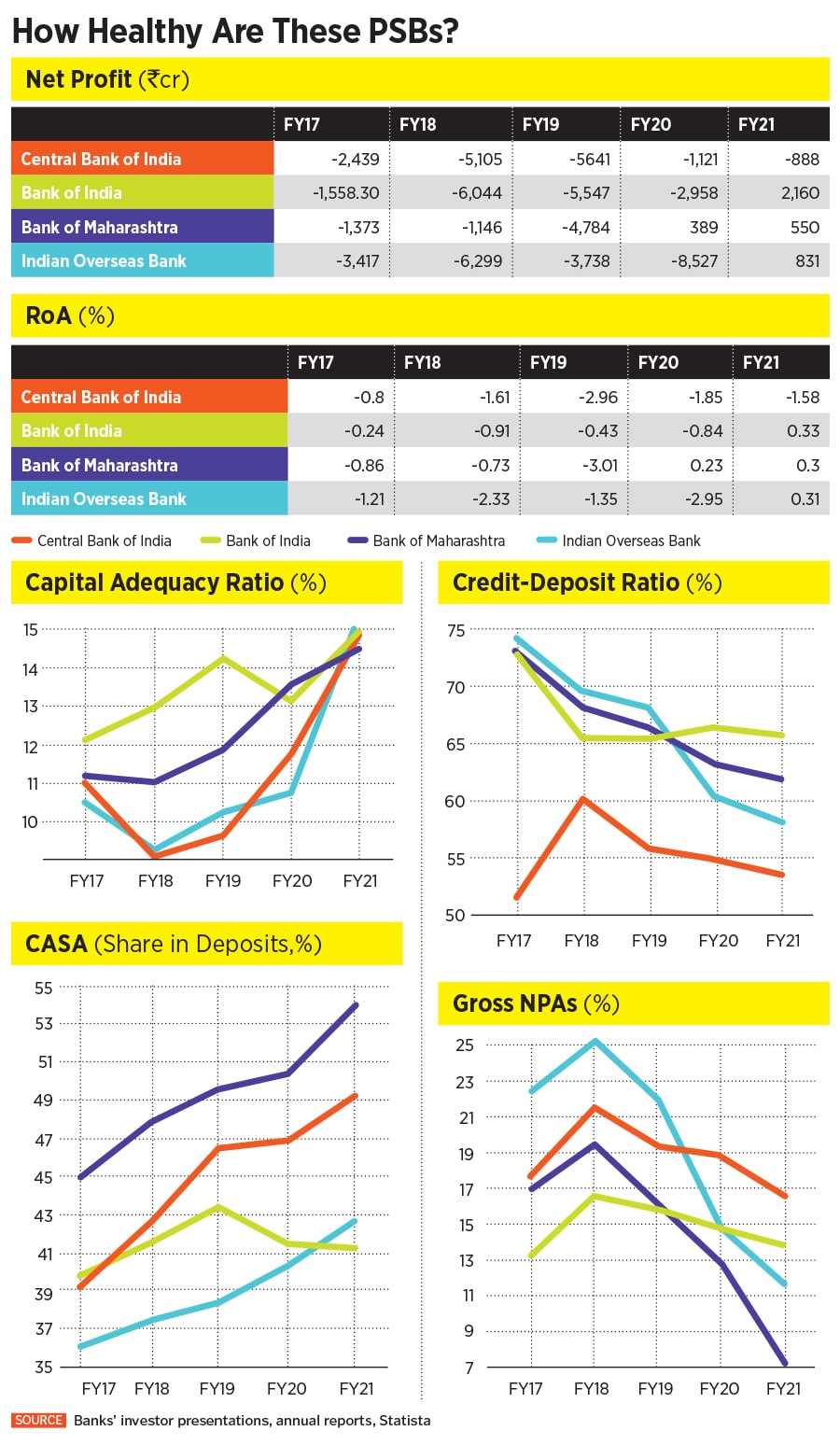

The names of four banks—Central Bank of India, Bank of India, Bank of Maharashtra and Indian Overseas Bank—are doing the rounds as potential candidates that could be privatised, despite the Niti Aayog shortlisting Central Bank of India and Indian Overseas Bank.

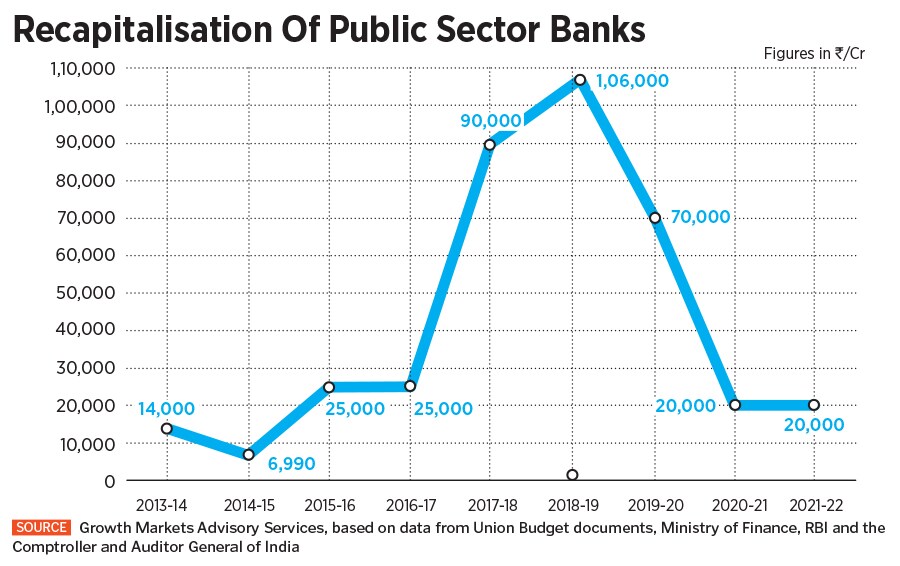

But the real issue is, are these banks ‘privatisation-ready’? There is very little evidence to suggest it. The second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic has affected profitability, productivity, asset quality and financial management at these banks. A new investor will need to infuse sizeable fresh capital, even after years of government support through recapitalisation for these banks. Sourcing the right talent has also been a battle for PSBs; banks that were part of the government-induced 2019 mega-merger are still struggling to find the right talent to manage complex risk management issues and leverage new-age fintech solutions.

Any move to retrench the existing workforce during privatisation will be met with stiff resistance at all these unionised banks. Legislative changes to bring these banks under the Companies Act 2013 are being debated, but we are also far from evaluating the accurate valuations for these banks, beyond book value and financials.

It will be a tough haul for the government machinery, lawyers and investment bankers to complete all of this smoothly over the next nine months. And, in reality, the bank management and employees are unlikely to have a meaningful say in the privatisation process.