Foreign banks in India: Leaner, but battle-ready

Each banking crisis amplifies fears of a risk to financial stability and the capability of foreign banks to withstand it. In India, losing share in deposits and lending activity may not make for a pretty matrix, but most foreign banks have doubled down on their strengths to battle domestic heavyweights

Citibank India’s $1.4 billion sale of its consumer banking business to Axis Bank in 2022-23

Image: Vivek Prakash/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Citibank India’s $1.4 billion sale of its consumer banking business to Axis Bank in 2022-23

Image: Vivek Prakash/Bloomberg via Getty Images

In the few weeks starting March, visualisations of 2008 had started to appear in peoples’ minds: Of large global banks shuttering, bankers getting fired and regulators taking collective action to arrest a contagion effect. The United States has already seen the collapse of three banks. Last month’s rescue of Swiss giant Credit Suisse by longtime rival UBS Group, through a $3.2 billion bailout, has increased the risk to financial stability. Inflation across most economies remains stubbornly high, which means interest rates will continue to rise and the impact of which on liquidity and the pace of growth is a given.

The Reserve Bank of India has, in its April 7 monetary policy meeting, already paused its interest rates hike cycle—the repo rate has risen cumulatively by 250 basis points in the last 11 months starting May 2022—in a move seen to assess not just the impact of these actions but also the evolving financial stability risks overseas. While public sector banks (PSBs) have been urged by the government to review their exposure to the external stress, they will need to assess risks, diversification of deposits and any asset-liability mismatches.

Foreign banking activity in India, which dates back to over 160 years, has a different issue to tackle. Each tremor to a global banking system triggers different responses from a bank operating outside its home market, but the messaging usually always originates from the bank’s headquarters. The cost of operations, the returns and regulatory compliance issues become issues of discussion. These have all become relevant issues for foreign banks to deal with in recent years.

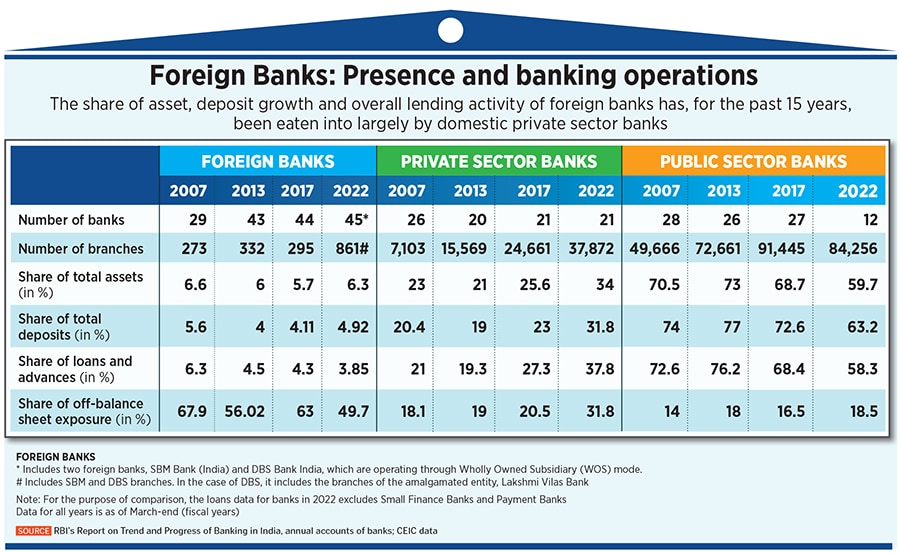

Foreign banks, at 45, constitute more than a third of the total of 137 scheduled commercial banks in India, which include public and private sector banks, payments banks, small finance banks and regional rural banks. Despite this meaningful presence for decades, they have just a 3.8 percent share of total loans and near five percent of total deposits, as of 2022 (see table). Their share of asset, deposit growth and overall lending activity has, for the past 15 years, been eaten into largely by domestic private sector banks.

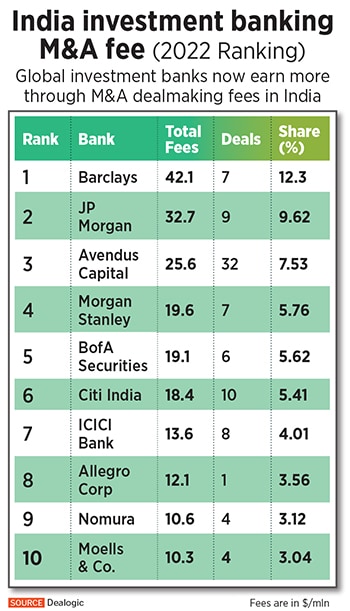

According to Dealogic, Barclays ended 2022 as a leader in M&A fees in India (see table) and global bonds, based on Bloomberg data. The list includes other heavyweights such as JP Morgan, Morgan Stanley, Citi, Bank of America Securities (BofA) and Nomura. Global investment banks now earn more through M&A deal making fees in India, than in China, indicating their shift away from the Chinese economy, which has yet to shrug off the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic.

According to Dealogic, Barclays ended 2022 as a leader in M&A fees in India (see table) and global bonds, based on Bloomberg data. The list includes other heavyweights such as JP Morgan, Morgan Stanley, Citi, Bank of America Securities (BofA) and Nomura. Global investment banks now earn more through M&A deal making fees in India, than in China, indicating their shift away from the Chinese economy, which has yet to shrug off the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic.