Heat, steam & perception: Inside Triveni Turbine's audacious global gambit

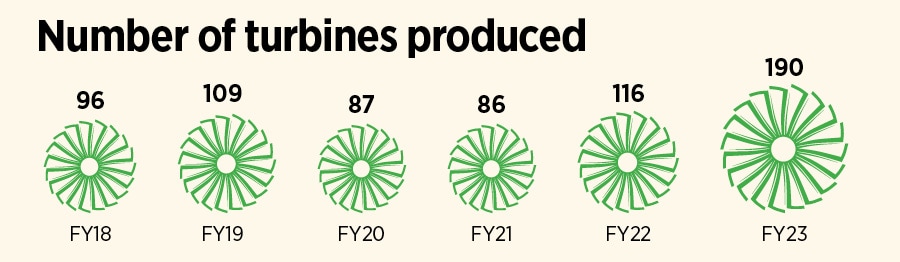

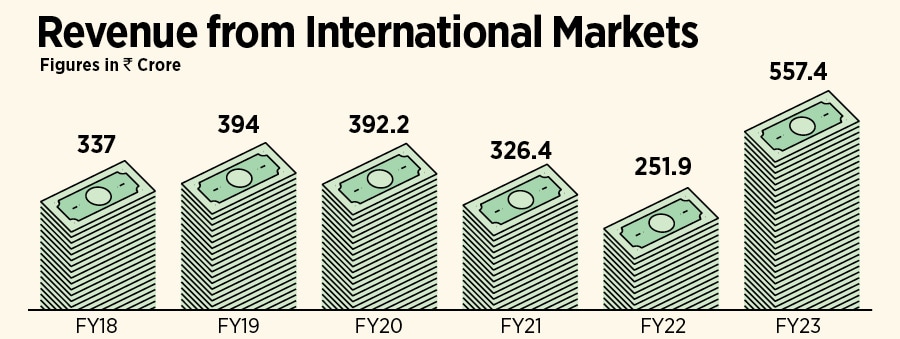

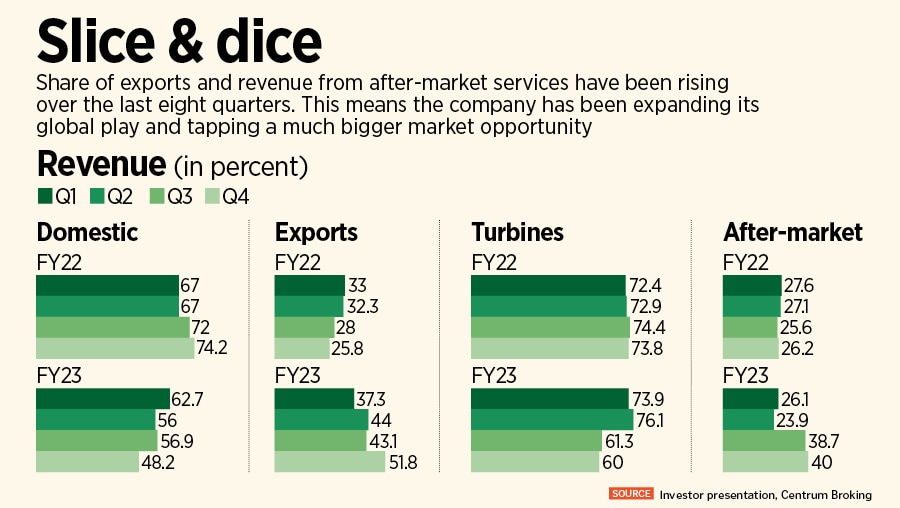

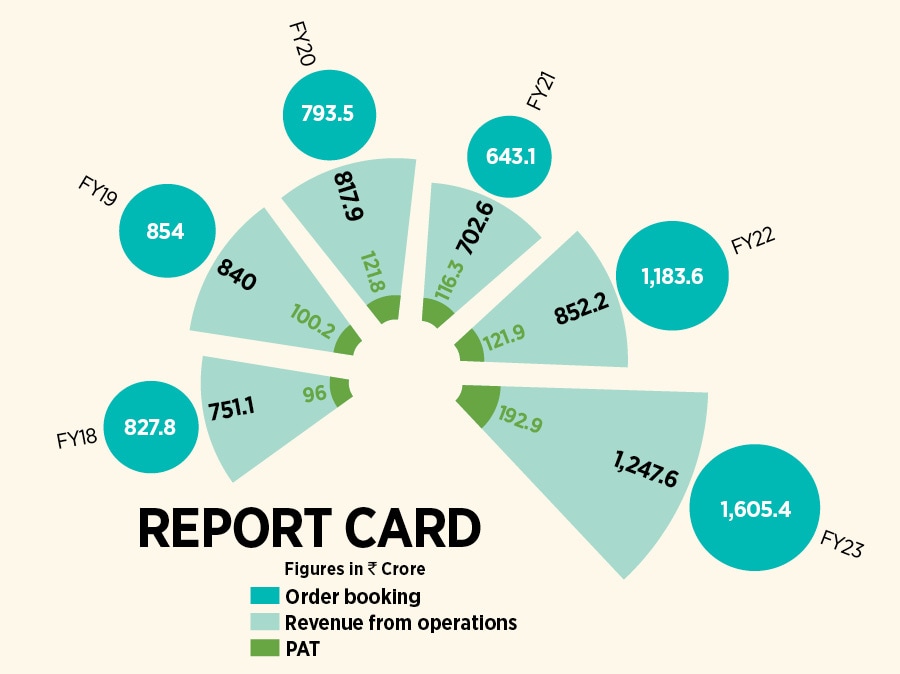

Triveni Turbine has posted its best fiscal performance in over a decade. With contribution from foreign markets growing at a faster clip, can India's biggest steam turbine maker engineer a playbook for a dominant global play?

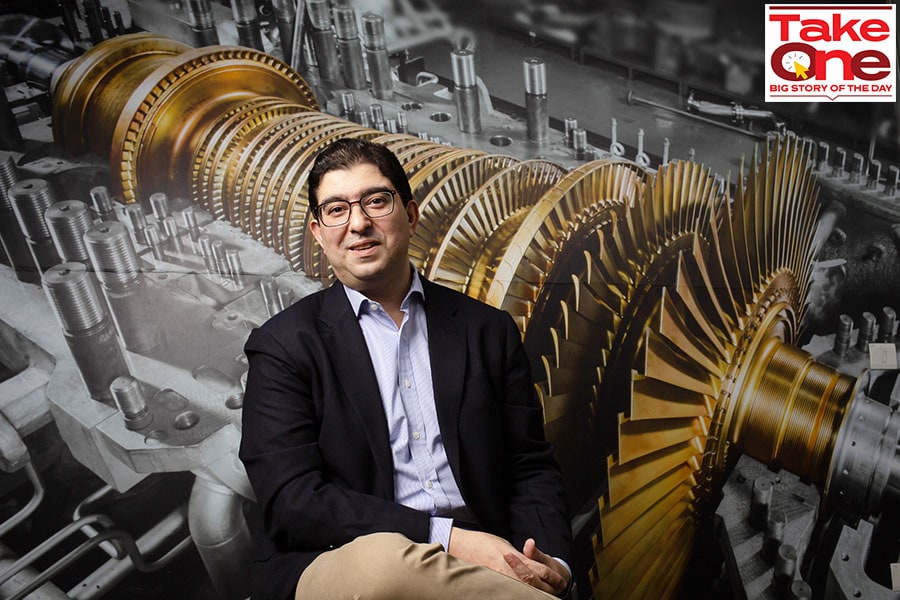

Nikhil Sawhney, MD and vice chairman of Triveni Turbines

Image: Madhu Kapparath

Nikhil Sawhney, MD and vice chairman of Triveni Turbines

Image: Madhu Kapparath

Noida, Uttar Pradesh May 2023. “The only thing constant for us is the heat,” says Nikhil Sawhney. It’s May. The scorching summer in Delhi-NCR had forced commuters to stay off the road, and the brave ones stepping out in the blazing sun find themselves running out of steam. Sawhney, somehow, is ice-cool, even as he is in the business of heat. The MD and vice chairman of Triveni Turbines, India’s biggest industrial steam turbine maker, says he cannot take his feet off the fire pedal because they have to be ahead of competition. “The heart and soul of the steam turbine is the fluid dynamics,” maintains Sawhney, as he starts explaining the nuances of the steam turbine.

Five minutes into the conversation, the strong central air conditioning of our meeting room on the eighth floor of the Express Trade Towers starts to freeze the cabin. “Do you want me to turn off the AC,” asks Sawhney, a suave Cambridge graduate who joined the family business of sugar in 1999, went on to study MBA from Wharton in 2002, and came back to India to be inducted into the turbine division of Triveni Engineering in 2004.

The AC is put to sleep, and the second-generation entrepreneur gets back to what he does best: Talk about heat, steam and turbines. “We set unrealistic benchmarks of where we think our competition is or could be,” Sawhney says, explaining how the DNA of ‘taking the heat’ got ingrained in the company, which got demerged from the parent entity in 2010, formed a joint venture in the same year with GE Oil & Gas to design, manufacture, supply, sell and service steam turbines in 30-100 MW in domestic and global markets. “We do this (benchmarking) so that we can constantly be ahead of others,” he adds.

Back in the 2000s, Sawhney got to see another side of steam: Burn. For steam turbine makers, India has been a low-cost and not a lucrative market. Global markets are where manufacturers make more money, and it’s in the foreign markets where quality, credibility and, most importantly, perception matters. India players, unfortunately, were singed by poor brand perception, and it had nothing to do with quality. It’s not that Triveni never had technical collaborations. Back in 1968, the first steam turbine was delivered in partnership with the UK's Peter Brotherhood. The arrangement continued till late 90s, and then Triveni decided to carve out an independent path. “We decided to invest in ourselves, in R&D and engineering,” recalls Sawhney. “We needed to back ourselves,” he adds.