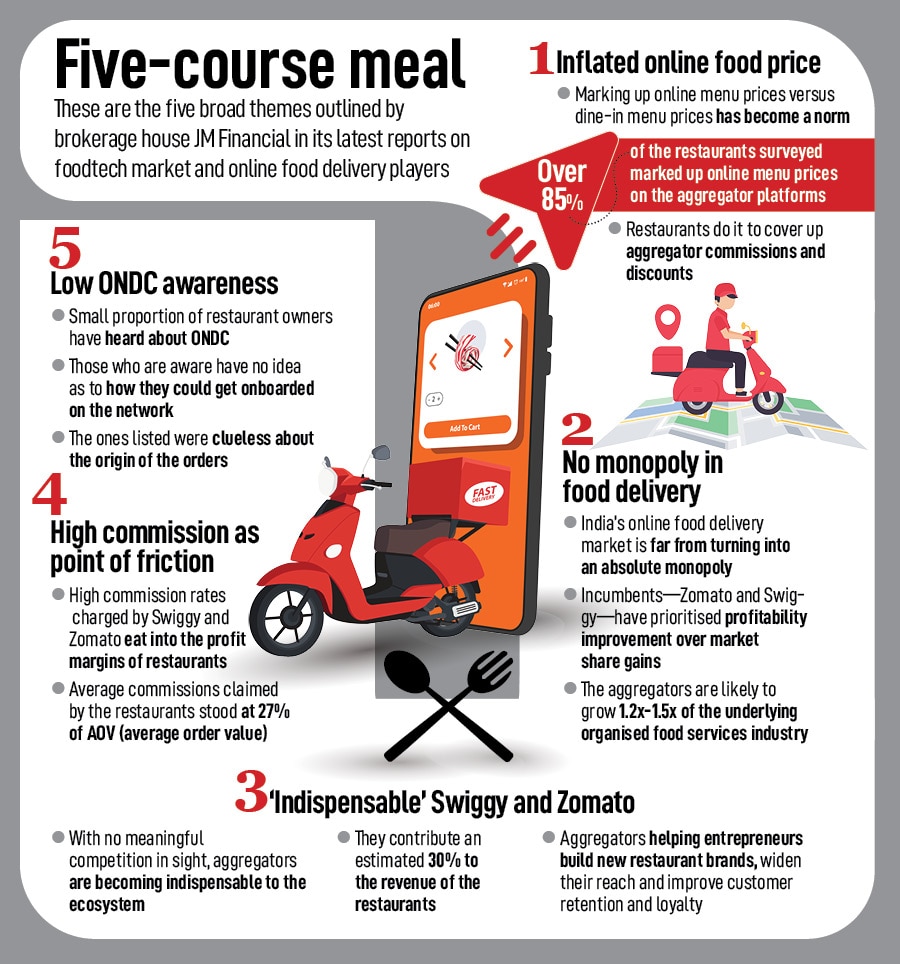

Mark-up and deliver: Why you can't count on online food discounts

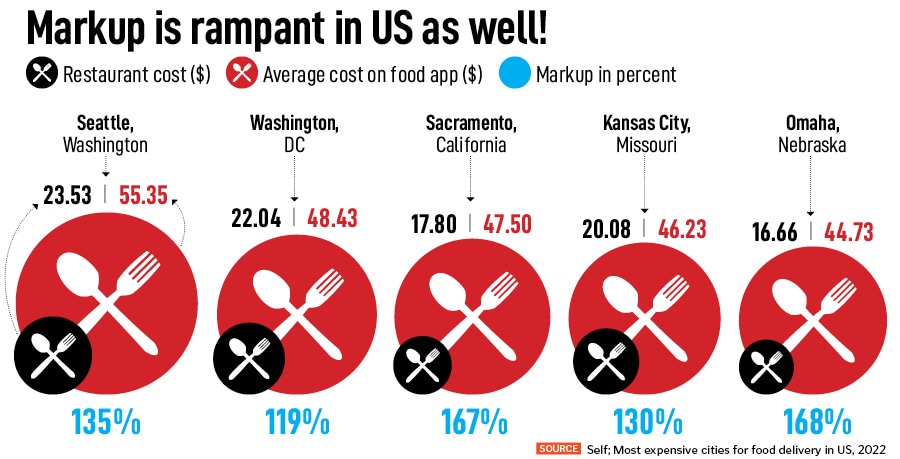

With most restaurants jacking up their online menu prices as compared to in-store rates, the discounts on Swiggy and Zomato turn into a farce. The trend is likely to stay as the foodtech duopoly gets deeply entrenched, and consumer activism goes missing

If monopoly hurts, then duopoly also does no good. It can create barriers for new entrants, limiting competition and stifling innovation.

If monopoly hurts, then duopoly also does no good. It can create barriers for new entrants, limiting competition and stifling innovation.

Let’s start with the first side of the coin. “Restaurants are forced to resort to such practices due to steep commissions charged by Swiggy and Zomato,” laments Savar Malhotra, working partner at Delhi-based The Embassy Restaurant, which traces its origin to 1948. “I have not yet added GST,” he says, adding that the bleeding food delivery aggregators are trying to squeeze restaurants as much as possible to reduce their bulging losses. “They (aggregators) are a pain for restaurants and are trying to make a profit by charging more from food players,” he rues. Restaurants, Malhotra underscores, are the first side of the coin.

Let’s analyse the second side of the same coin. “Aggregators are unlikely to voluntarily stop such practices,” notes JM Financial in its latest report on the foodtech sector. The practice won’t stop, the brokerage house underlines in its note released late last month, unless there are regulatory changes or a severe backlash from customers. “Both of which do not seem to be happening at present,” the report adds. While theoretically, the organised food services industry can survive without the aggregators, practically that is unlikely to ever happen. “Aggregators now contribute around 30 percent to the turnover of restaurants listed on their platforms,” the report notes, pointing out the value of the ‘second’ side of the coin: Aggregators.