ONDC is India's next big bet after UPI

The open network is re-inventing ecommerce to level the playing field between online and offline players and loosen the grip of Big Tech. The opportunity is massive but so are the obstacles

Rosbin P B, ONDC user and owner of Greenmart supermarket

Image: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India

Rosbin P B, ONDC user and owner of Greenmart supermarket

Image: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India

When Rosbin PB, a 32-year-old shopkeeper, joined hands with the owner of a 450 square-foot local convenience store in Bengaluru’s Indiranagar, it had a small but dependable customer base. IT workers who lived in the neighbourhood bought their groceries and daily supplies from the shop. But Rosbin wanted more.

He borrowed money, expanded the shop, and registered on Dunzo. Orders routed through the hyperlocal delivery service shot up to 700 per day in a matter of months.

Then, Dunzo decided to open its own dark store in the neighbourhood. Rosbin says the number of orders slashed to 80 per day. “They give preference to their own store, naturally,” he says. “We have to accept whatever these companies decide. We have no choice.”

That’s changing now. Rosbin has registered on the Open Network for Digital Commerce or ONDC—a network that enables his little shop to be visible to online buyers shopping on any app, so long as that app is aligned with ONDC.

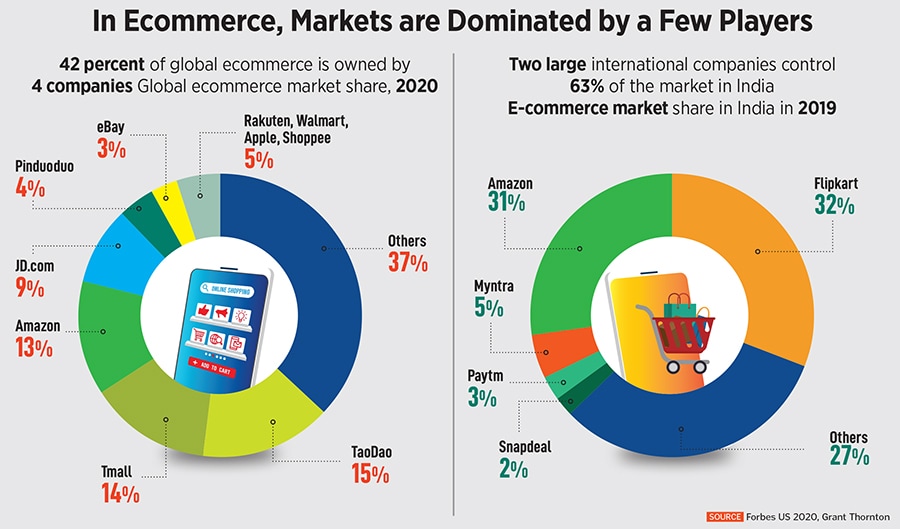

So when a customer opens his favourite shopping app—Paytm, for example, which is part of the network—and clicks on the ONDC icon, he will be able to find products from all sellers who are part of the network, not just sellers registered with Paytm. So far, 36,000 sellers across 236 cities have registered on ONDC including large ones like HUL and ITC, as well as smaller setups like Rosbin’s Green Mart.