What Koreans can teach Americans and Europeans on cracking India's auto market

Ford and Hyundai entered India at the same time, and as the first shuts shop in the country, the second has become hugely successful

SS Kim MD & CEO, Hyundai Motor India Limited, says that Hyundai India's product planning and development processes are based on India. Image: Madhu Kapparath

SS Kim MD & CEO, Hyundai Motor India Limited, says that Hyundai India's product planning and development processes are based on India. Image: Madhu Kapparath

It’s a tale of contrasting fortunes. And in many ways, it’s akin to David’s conquest over Goliath. Twenty-five-years ago, American automobile giant Ford, having revolutionised global automobile manufacturing, came to India’s shores with serious ambitions of striking gold. Ford was a pioneer in the assembly line manufacturing process, and remained an inspiration to many Indians who had long been deprived of global automobiles as India remained a protectionist regime.

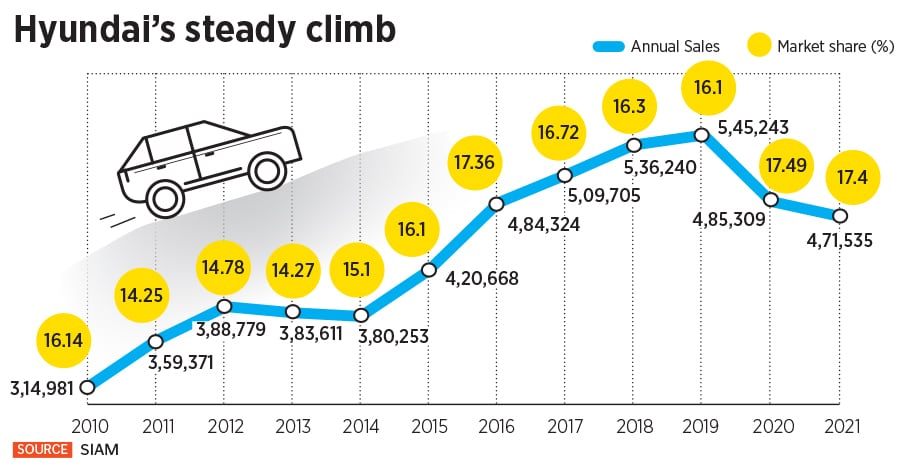

Around the same time, Hyundai, a relatively unknown South Korean car manufacturer, having forayed into the US market barely a decade earlier, also came knocking to capitalise on India’s fledgling economy, which looked set for rapid growth. Both Hyundai and Ford set up their factories in Chennai.

Now, 25 years later, one has gone on to become India’s second-largest carmaker, while the other has shut shop.

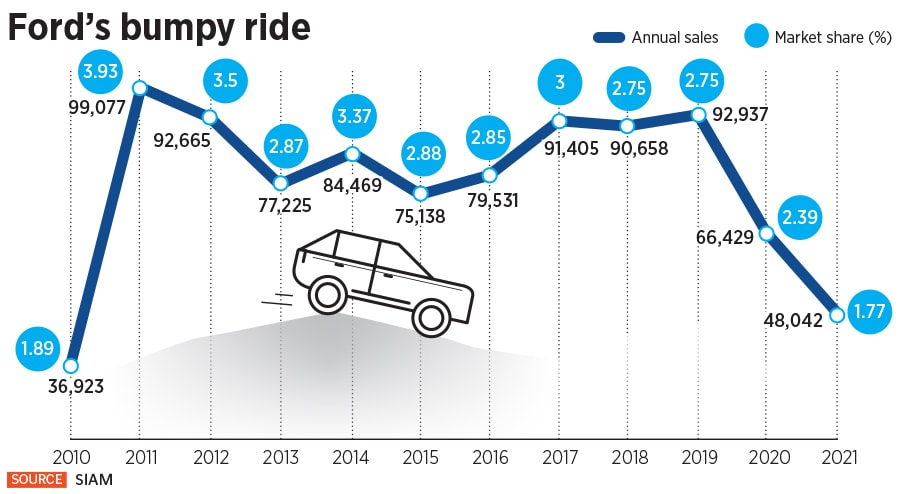

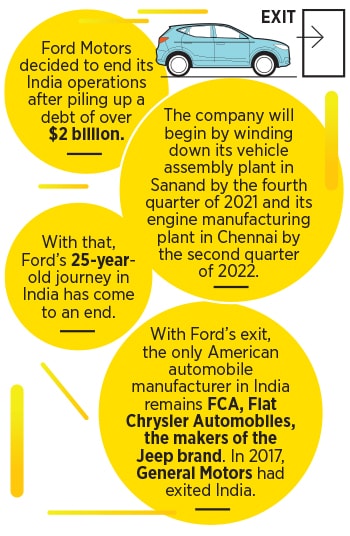

In early September, Ford Motors decided to end its India operations after piling up a debt of over $2 billion, making the Detroit-headquartered automaker’s India operations unsustainable. The decision to pull out of the world’s fourth-largest automobile market has also put a near end to an American dream in India. With Ford’s exit, the only American automobile manufacturer in India remains Fiat Chrysler Automobiles (FCA), makers of the Jeep brand. In 2017, General Motors had exited India.

“Despite investing significantly in India, Ford has accumulated more than $2 billion of operating losses over the past 10 years, and demand for new vehicles has been much weaker than forecast,” said Jim Farley, Ford Motor Company’s president and CEO, in a statement. The company will begin by winding down its vehicle assembly plant in Sanand, Gujarat, by the fourth quarter of 2021 and its engine manufacturing plant in Chennai by the second quarter of 2022.

Former US Secretary of State John Kerry looks over the machines at a Ford India automotive factory with plant manager Kal Kearns (behind Kerry) in Sanand January 12, 2015. Image: Rick Wilking / Reuters

Former US Secretary of State John Kerry looks over the machines at a Ford India automotive factory with plant manager Kal Kearns (behind Kerry) in Sanand January 12, 2015. Image: Rick Wilking / Reuters Hyundai did not waste any time in developing a made-for-India car, which offered many firsts to the consumer. For example, a multi-port fuel injection engine with three valves in the entry-level segment instead of carburetors, along with power steering and rear seat belts. At its Chennai plant, the carmaker brought many of its South Korean makers and vendors, who localised the manufacturing processes, while maintaining international standards and controlling costs of body parts, headlights and engine parts, among others.

Hyundai did not waste any time in developing a made-for-India car, which offered many firsts to the consumer. For example, a multi-port fuel injection engine with three valves in the entry-level segment instead of carburetors, along with power steering and rear seat belts. At its Chennai plant, the carmaker brought many of its South Korean makers and vendors, who localised the manufacturing processes, while maintaining international standards and controlling costs of body parts, headlights and engine parts, among others.

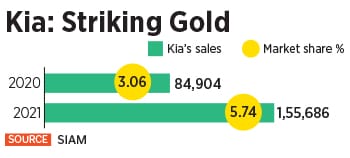

The phenomenal success of Kia and Hyundai is also an eye opener for struggling European brands in India, including the likes of

The phenomenal success of Kia and Hyundai is also an eye opener for struggling European brands in India, including the likes of