Why the rural economy isn't out of the woods yet

Rural spending fell to 2.8 percent in the previous quarter but most corporate honchos expect demand to pick up ahead of the festive season even as some caution that there are no visible green shoots of a meaningful recovery in rural markets yet

Delay in the sowing of kharif crops, which reduced the demand for farm labour. Besides, the withdrawal of some pandemic sops squeezed spending and rural wages remained flattish.

Image: Avijit Ghosh/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

Delay in the sowing of kharif crops, which reduced the demand for farm labour. Besides, the withdrawal of some pandemic sops squeezed spending and rural wages remained flattish.

Image: Avijit Ghosh/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

The world’s most populous country is trying to revive its rural markets. Despite a recent uptick in demand, the signs of stress in India’s hinterlands are hard to rub off. Almost 70 percent of its people live in rural areas where agriculture is an important source of income. Yet, farming contributes less than 20 percent to the country’s GDP. In cracking this conundrum lies the biggest challenge and opportunity for small and big industry players. The mixed signals from towns and villages doesn’t make this task any easier.

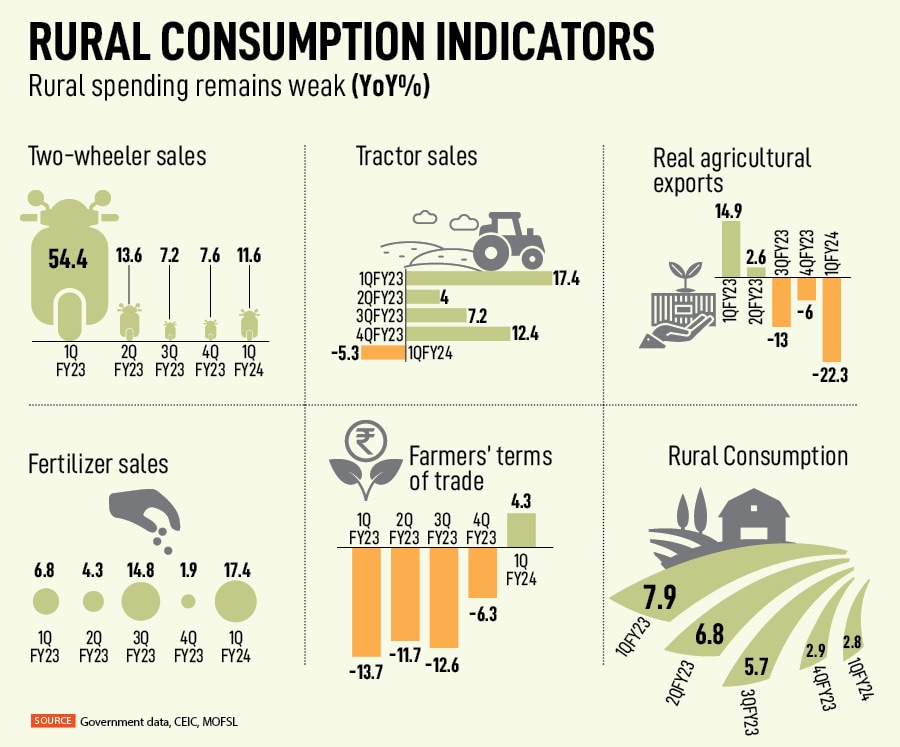

There are ten proxy markers for gauging the state of the rural economy. These include two-wheeler sales, tractor sales, farmers’ terms of trade, agricultural exports, real agricultural GVA, farm credit, reservoir levels, and fertiliser sales. A simple average of these indicators, according to economists, suggests that the rural economy is not out of the woods.

Rural consumption fell to a six-quarter low of 2.8 percent year-on-year in Q1FY24 in comparison to 7.9 percent in Q1FY23 (see table). There was a big drop in farm exports (fastest decline in eight years) and tractor sales (first contraction in five quarters) that slumped to 22.3 percent and 5.3 percent respectively in the April-June period. The blow was partially softened by an improvement in the farmers’ terms of trade and fiscal rural spending which rose by 4.3 percent and 7.5 percent each.

As per the 77th round of the National Statistical Office (NSO) survey, around 49 percent of rural household income comes from wages, approximately 37 percent from crop production, and close to 14 percent from non-farm business, livestock and rent. Currently, the rural unemployment rate hovers close to 8 percent and the demand for work under the rural employment guarantee scheme increased by 15.2 percent in July over the previous year. One reason for this could be the delay in the sowing of kharif crops, which reduced the demand for farm labour. Besides, the withdrawal of some pandemic sops squeezed spending and rural wages remained flattish.