Varun and Ghazal Alagh's Mamaearth empire is built on the foundation of frugality

Profitable businesses don't happen by serendipity, there has to be a plan—and the Alaghs have led with their middle class values of frugality, to deliver three straight years of profit at beauty and skincare brand Mamaearth

Varun Alagh, co-founder & CEO,

Honasa Consumer and Ghazal Alagh, co-founder and chief innovation officer, Honasa Consumer

Image: Amit Verma

Varun Alagh, co-founder & CEO,

Honasa Consumer and Ghazal Alagh, co-founder and chief innovation officer, Honasa Consumer

Image: Amit Verma

January 2020, Sector 44, Gurugram. Ishaan Mittal was stunned. “It was probably the smallest office I had ever seen,” recounts the venture capitalist. On a Monday morning, the principal at Sequoia India landed in Delhi from Bengaluru, navigated smog and congested roads to reach Honasa Consumer’s office in Gurugram. He wanted to quickly wrap up the last-minute formalities before closing the series B round of funding. Ghazal and Varun Alagh were busy with the R&D team cramped in the basement of a building where the parent company of skincare and beauty brand Mamaearth was chaotically nestled.

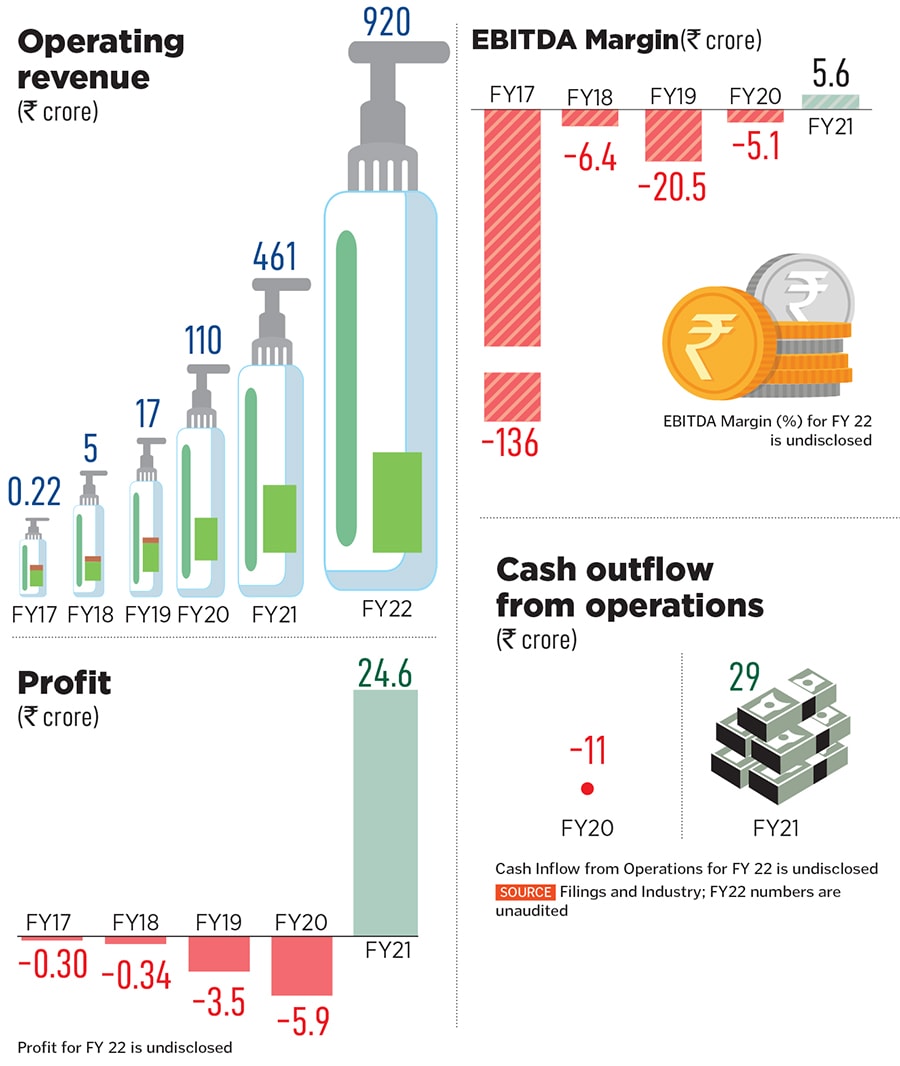

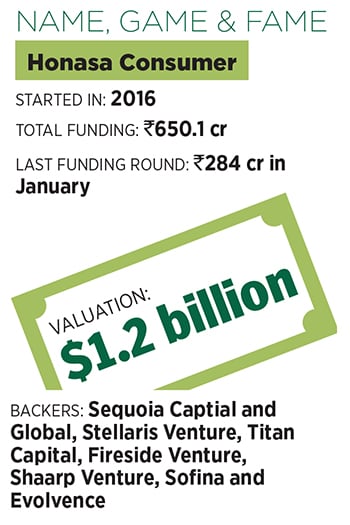

Mittal was dazzled. He expected some sort of visual relief. But there was none. “This was the beauty about the co-founders,” underlines Mittal, now managing director with Sequoia India. He explains his ‘pleasant state of surprise’. Started in 2016 by Ghazal and Varun Alagh, Mamaearth had raced to an operating revenue of ₹17 crore in three years—₹22.19 lakh, ₹5 crore and ₹17 crore in FY17, FY18 and FY19, respectively. The brand, which started with toxin-free babycare products, was now striking a run-rate of ₹100 crore for FY20.

Mittal now talks about another pedigree of the startup, which gave it enough room to flex its elbows. The direct-to-consumer brand had raised over $4 million from Fireside Ventures, Titan Captial and a bunch of angels in its seed and series A round till January 2020. So a company of this size was expected to have a slightly spacious and more modest corporate headquarters. Right? “Well, this is what I presumed,” says Mittal, who had seen a bulk of startups graduate to a much bigger space after getting funded. The Mamaearth co-founders, though, were the odd ones out. “They were immensely frugal,” he says.

The constricted size of the office, however, had nothing to do with the financials of the startup. Mamaearth has posted three consecutive years of losses—₹30 lakh, ₹34 lakh and ₹3.5 crore in FY17, FY18 and FY19, respectively—and was expected to bleed more in FY20. Queerly, Mittal sensed an impending tipping point. Sequoia India led the series B round of funding in January 2020 when Mamaearth raised $20 million. “Profitable businesses don’t happen by serendipity,” he maintains. “There has to be a plan.”

The constricted size of the office, however, had nothing to do with the financials of the startup. Mamaearth has posted three consecutive years of losses—₹30 lakh, ₹34 lakh and ₹3.5 crore in FY17, FY18 and FY19, respectively—and was expected to bleed more in FY20. Queerly, Mittal sensed an impending tipping point. Sequoia India led the series B round of funding in January 2020 when Mamaearth raised $20 million. “Profitable businesses don’t happen by serendipity,” he maintains. “There has to be a plan.”

Back in 2018, the husband-wife duo was busy executing a close-fisted plan. Mamaearth roped in actor Shilpa Shetty Kundra to endorse the brand. Analysts and critics reacted strongly. “Another D2C startup burning money,” was the noise. There was a fitting context for the caustic reception. The combined losses of five of India’s most funded internet firms—Paytm, Flipkart, MakeMyTrip India, Swiggy and Zomato—stood at ₹7,800 crore in FY18, according to data quoting business intelligence research platform Tofler. The Alaghs, though, stayed unfazed. “We did an equity deal with the celeb. She invested in the company, and we didn’t pay her,” says Varun. “Humne cash bachaya [we saved cash],” chips in Ghazal. “Having clarity on what not to do is more important than aligning what all to do.”

Another instance of keeping costs under control was delaying Mamaearth’s debut on television. Pressure, again, was immense and thrusted quite early. “Itna paisa pada hua hai bank mein, tum TV ad kar lo [there is so much of money lying in the bank. Do a TV ad],” was a strong pitch made by a bunch of VCs in 2018. “This would help in multiplying sales,” they argued, rooting for an aggressive marketing and promotional blitzkrieg. Yet another suggestion was to expand outside the country. After all, new geographies would lead to a spurt in sales and widening of consumer base. The third advice was to foray into the home care segment. Again, the move made sense. HUL and P&G were cited as great examples and the huge total addressable market (TAM) of the segment was dangled as a carrot.

Another instance of keeping costs under control was delaying Mamaearth’s debut on television. Pressure, again, was immense and thrusted quite early. “Itna paisa pada hua hai bank mein, tum TV ad kar lo [there is so much of money lying in the bank. Do a TV ad],” was a strong pitch made by a bunch of VCs in 2018. “This would help in multiplying sales,” they argued, rooting for an aggressive marketing and promotional blitzkrieg. Yet another suggestion was to expand outside the country. After all, new geographies would lead to a spurt in sales and widening of consumer base. The third advice was to foray into the home care segment. Again, the move made sense. HUL and P&G were cited as great examples and the huge total addressable market (TAM) of the segment was dangled as a carrot.