The anomaly of doing whatever it takes to revive growth

The RBI needs to focus on its mandate of inflation control, and the onus is on the government to do the bulk of the lift off to drive investments and growth as the economy grapples with multiple challenges

Monetary policy needs to be normalised quickly as any delay risks even bigger rate hikes down the road and more policy uncertainty, which could be painful

Monetary policy needs to be normalised quickly as any delay risks even bigger rate hikes down the road and more policy uncertainty, which could be painful

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur

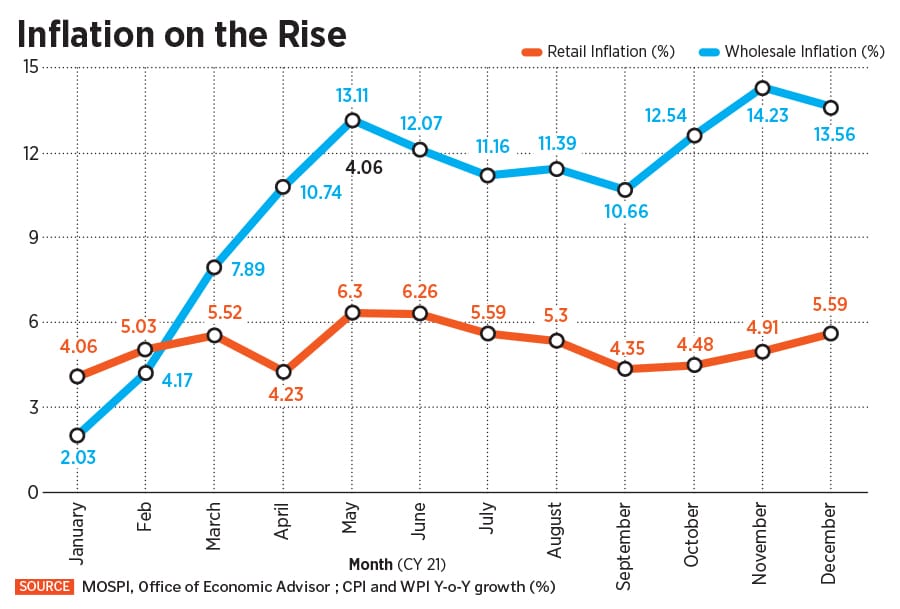

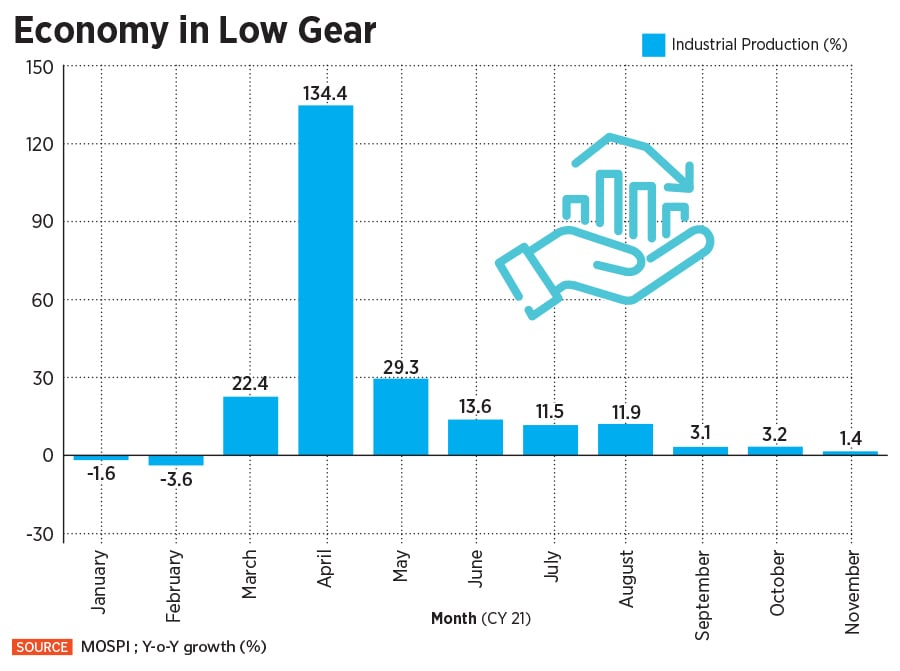

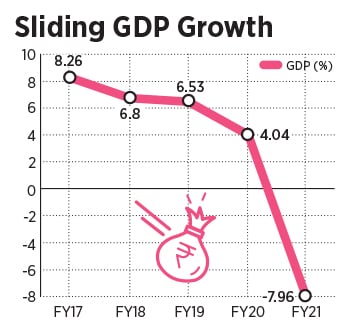

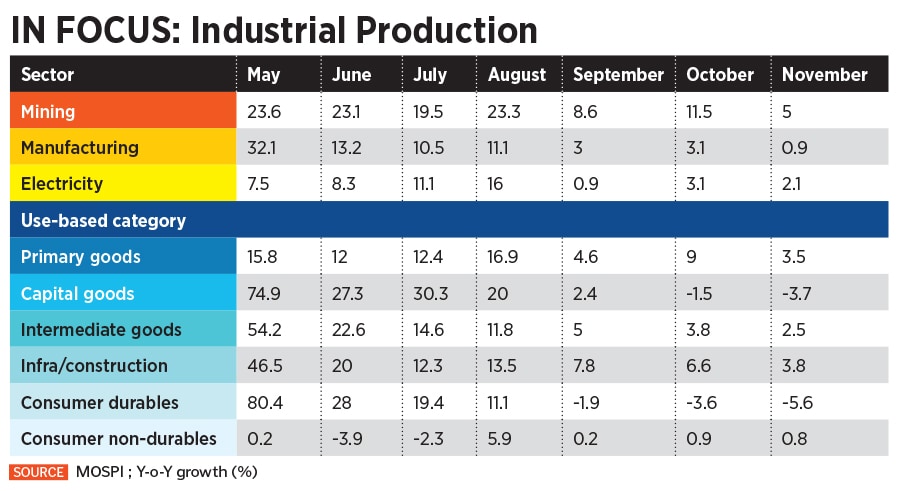

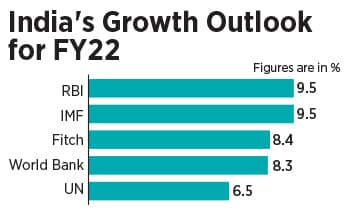

Unprecedented times call for unprecedented measures that come with untold risks. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI), like central banks worldwide, made this leap of faith as it scrambled to respond to the once-in-a-lifetime pandemic by reducing interest rates and injecting excess liquidity to cushion the economy from acute disruptions. Nearly two years later, there is a new mutation of the coronavirus; inflation is disturbingly high (see chart) but economic growth is anaemic; the repo rate is at an all-time low of 4 percent but consumption and investment demand are in low gear; industrial production is bleak but stock markets are cheerful.

Against this backdrop, despite growing inflationary challenges, the RBI has said it will remain committed to continue its accommodative stance until there are signs of durable growth in the economy. In other words, the central bank prefers a status-quo till the time there is a clear uptick in the investment cycle.

Pranjul Bhandari, chief India economist at HSBC, argues that the pace of acceleration in investments in the economy depends on a high degree of policy certainty around macroeconomic stability. "Perhaps the RBI now needs to think differently and focus on its mandate of inflation control. That in itself adds a layer of policy stability that will drive investments over time, rather than the other way around—where it will not normalise monetary policy until investment rises,” she adds.

The RBI cannot afford to focus just on growth, says Upasna Bhardwaj, senior economist, Kotak Mahindra Bank. “We need to ensure we don't get into an inflationary environment which can choke growth,” she cautions. In fact, hovering above 5 percent during the pandemic period, core inflation has been elevated long before rising global inflation rung alarm bells.

After rising rapidly, goods production has indeed plateaued at about pre-pandemic levels. There is hope that services demand does better, but both goods and services demand are driven by incomes, elaborates Bhandari. “We will start to see growth slowdown in the second half of FY23 once pent-up demand has run its course and we realise we don't have a new growth driver,” she says.

After rising rapidly, goods production has indeed plateaued at about pre-pandemic levels. There is hope that services demand does better, but both goods and services demand are driven by incomes, elaborates Bhandari. “We will start to see growth slowdown in the second half of FY23 once pent-up demand has run its course and we realise we don't have a new growth driver,” she says.

Economists and analysts Forbes India interacted with stress on the need for the government to implement targeted fiscal measures and policy reforms to address the ailing sectors of the economy. They also call for continuation of

Economists and analysts Forbes India interacted with stress on the need for the government to implement targeted fiscal measures and policy reforms to address the ailing sectors of the economy. They also call for continuation of