Linking CEO Compensation with ESG markets is the worst idea: Rajeev Peshawaria

The CEO of the Temasek-backed Stewardship Asia Centre in Singapore, on why capital, incentives and regulation may not be enough to drive responsible corporate behaviour towards climate and sustainability

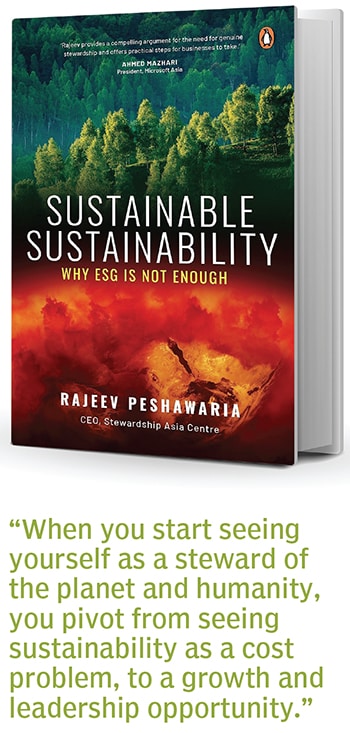

Why it’s important for leaders to have interdependence, ownership mentality, a long-term view and creative resilience, and why sustainability is not a cost problem, but a leadership challenge.

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur

Why it’s important for leaders to have interdependence, ownership mentality, a long-term view and creative resilience, and why sustainability is not a cost problem, but a leadership challenge.

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur

The ESG (environment, social, governance) framework that companies follow to be more accountable towards climate and environmental sustainability is often reduced to box-ticking and greenwashing, says Rajeev Peshawaria, CEO of the Stewardship Asia Centre. The Singapore-based non-profit and think tank is founded under Temasek Trust (the philanthropic arm of investment company Temasek Holdings), and looks at how environmental and social sustainability can work for businesses.

Q. Why do you propose the term ESL (environment, social, leadership) instead of the conventional ESG?

So, environment and social are existential challenges, and governance is supposedly the mechanism that is going to help businesses address those challenges. So, we [at Stewardship Asia Centre] looked at whether ‘G’ was working. We asked a lot of board directors around the world, ‘How do you spend your time in board meetings?’. It turned out that 60 percent of board time is spent on regulatory compliance, financial management and risk management. We asked them what are the things they didn’t spend enough time on as board members, and they said, sustainability, culture, leadership, talent, and innovation. So, it struck me, how is G is going to save us from E&S if we don’t focus on talent, sustainability and innovation?

We researched and talked to 100 companies around the world that were driving superior shareholder returns by addressing an environmental or social challenge, and were doing it profitably. We asked them two questions. Why do you do it? And how do they do it? The answer to the ‘why’ was they see themselves as stewards who need to take care of the planet and society. And the role of businesses is to make money, so they want to find profitable solutions to these challenges. Four specific values were common among these 100 companies.

First is interdependence, which is the belief that the more I do for the planet and society, the more my business is going to thrive, rather than the other way around. They don’t look at sustainability as a cost problem, they see it as a leadership challenge.

The second is that they take a long-term view. We have examples in our research of companies that are 200 or 300 years old, and they’ve had sustainability-first strategies from the get-go. One of the companies we talk about is the Tata group. Long before the first steel power plant came up, they were building schools, hospitals and community parks. Not because they were philanthropists. Jamsetji Tata knew very well that unless they build all that, how would they attract families to come and live there?

Third is taking ownership for the challenges that humanity is facing today, and use business as a means to address them. The fourth is creative resilience, which is not giving up until they find innovative solutions. And then the companies pursue a purpose based on these four values, which creates a collective better future, not just for the shareholder, but all stakeholders. This became the steward leadership model that the book talks about, and we now recommend that ESG should be upgraded to ESL, where L stands for a specific form of leadership called steward leadership.

Rajeev Peshawaria, CEO, Stewardship Asia Centre

Rajeev Peshawaria, CEO, Stewardship Asia CentreQ. Apart from the Tata group, are there other companies from India?

We have an initiative called SL [Steward Leadership] 25. Every year we invite self-nominations from companies that are solving an environmental or social challenge profitably. An international jury selects the 25 best stories and we publish them. There are two-three companies from India that have been on the list. One, for example, is the Avatar Group. Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) has been on the list for a couple of years. We are getting a lot of applications from India.

Q. Do you only look at legacy companies, or even startups?

SMEs and social enterprises is one category, and large caps is another.

Also read: Does it pay to link executive compensation to ESG goals?

Q. There’s this conversation about how it’s easier for larger corporates to adopt ESG, but SMEs often lose out because of lack of resources. Is that something you’ve seen?

That’s the popular belief, right? ‘Sustainability is not for me because I’m still a small startup and can’t afford these costs’. But when you start seeing yourself as a steward of the planet and humanity, you pivot from seeing sustainability as a cost problem, to a growth and leadership opportunity.

Every large corporation today was an MSME at one time. The average lifespan of a company is 18 years, according to McKinsey. But we’ve got examples in our database of companies that are 100, 200, 300 years old, and we argue that they have been around for this long and growing profitably because they used a sustainability-first strategy from day one. In the history of wealth creation, ultra-amounts of wealth were created because an entrepreneur somewhere put a finger on the biggest pain points of society and found a profitable solution. Be it oil, electricity or railroads.

Today’s biggest pain points are climate change, socioeconomic inequality, and cyber vulnerability. Anybody that can find profitable solutions to this is going to make the next amounts of ultra-wealth.

Q. Given a high competition environment with fine margins, how do you integrate ESL practices, and also overcome, say, cultural resistance in companies?

As a leader, you have to ask yourself honest questions about your own values and purpose, be super clear, and have the courage that no matter what happens, you will not break those values. That’s the personal inner engineering work that needs to happen. How do you make a successful business based on that? You have to innovate and find profitable solutions.

A lot of people say that the consumer is not willing to pay extra for sustainability. And I say, no, big companies have billions of dollars in cash, trillions of dollars in some cases, so they cannot expect the consumer to pay extra for sustainability. The average person is already suffering with inflation. The top one percent of the world have more wealth than 6.9 billion people, and these rich people are the ones running the big companies. Their job is not to make the consumer pay, their job is to find innovative solutions for climate change and inequality. They have to build those innovation engines, invest in research and development, find profitable solutions, which make the life of the common person better and make them tonnes of money.

Q. Sustainability or ESG-linked investments are increasing, and assets under management are expected to reach $50 trillion by 2025. What do you think the venture capitalists or the private equity funds, or banks need to do differently to evaluate companies or investments?

We are at $43 trillion right now, which is a third of all assets under management in the world. So I have a couple of questions. Suddenly, how did one-third of all capital become ESG? Is it really ESG? Secondly, $43 trillion is not a small amount of money, why are we [the global temperature] moving towards 2.5 degrees rather than 1.5 degrees? According to estimates by the World Bank and the World Economic Forum, you need anywhere between $50 million and $100 trillion to meaningfully reverse climate change. We’re halfway there with $43 trillion and it’s growing with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 12 percent. So why are we not going in the right direction? Because it’s all greenwashing and box-checking. How much of that $43 trillion is going towards climate or social action? I don’t have the number, but I know it’s very little.

Capital, incentives and regulations are the three tools being used to drive responsible behaviour. That $43 trillion of capital is not doing it. Over 100 countries have passed new regulations, but people are finding loopholes, and even if they are following regulations, it’s at best minimising harm and not maximising good. And coming to incentives, the idea of linking CEO compensation with ESG markers is the worst possible idea. The belief in management circles is what gets measured and incentivised gets done. No, it doesn’t. What gets overly measured and incentivised gets misused. I report to you the numbers and the data that I want, which make me look good, so that I maximise my bonus. So, capital incentives and regulations are not going to cut it. We need steward leadership.

Q. How do you get more executives and businesses to be steward leaders?

I would be naïve to say everyone would adopt such values and want to create a collective better future. Eighty percent people will never adopt steward leadership. So then why are we talking? Because we don’t need them. If [late economist] Vilfredo Pareto is to be believed, we only need 20 percent of the people and 20 percent of organisations to embrace steward leadership, because the 80:20 rule says that 20 percent of the people do 80 percent of the magic. Right now, we are nowhere close to even 20 percent. So, all we need is two out of every 10 people to adopt steward leadership, and I think that’s doable.

(This story appears in the 28 June, 2024 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)