Lakshmi Vilas Bank-DBS India merger: Rocky road ahead

While the amalgamation seems like the best possible option for the cash-strapped bank, hurdles such as integrating technological platforms, limited cross-selling opportunities of products and cultural differences will have to be overcome

Photo: Abhirup Roy/REUTERS

Photo: Abhirup Roy/REUTERS

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has assisted the cash-strapped Lakshmi Vilas Bank (LVB) take its first tiny step to survival. The central bank has found a suitor and formulated an amalgamation plan with private lender DBS Bank India (DBIL)—the wholly-owned subsidiary of Singapore-based DBS Bank.

The road to the merger, though, is rocky and a tricky one, laden with hurdles, including integrating technological platforms, limited cross-selling opportunities of bank products, cultural differences and employee compensation issues, which the two banks have to deal with in coming months.

Investors, too, have signalled their concerns: The LVB stock is down by 36 percent to Rs9.95 at the BSE since the moratorium and a thrust-down amalgamation was announced by the RBI. The deadline to submit suggestions and objections to the amalgamation plan ends on Friday, November 20, following which the RBI will take a final call on the matter.

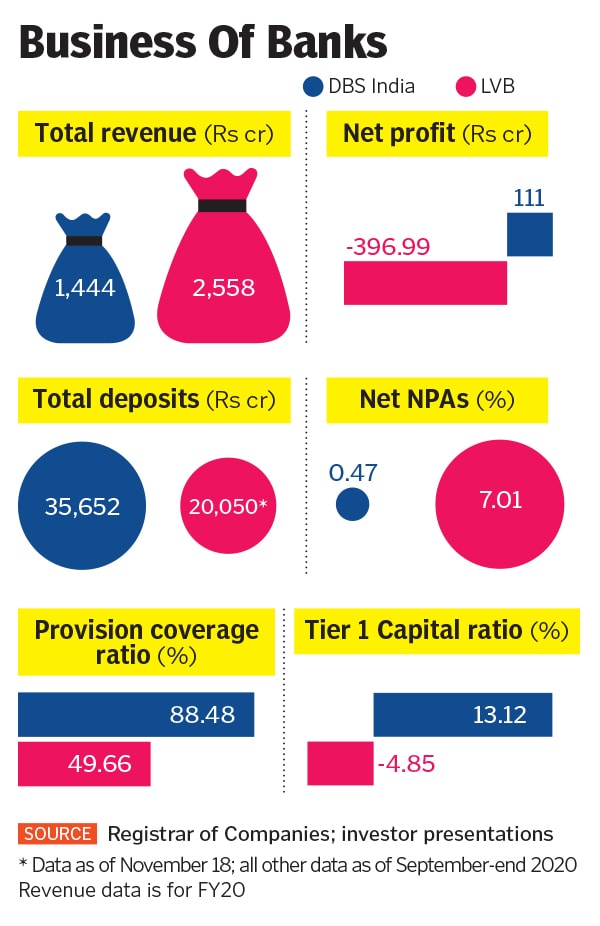

LVB is now under moratorium and its new administrator, TN Manoharan, appointed by the RBI, is focussed on ensuring the availability of cash through all banking channels for its customers, who appear keen to withdraw cash from the troubled bank. Deposits for LVB have fallen to Rs20,050 crore as of November 18 from Rs20,973 crore in the September-ended quarter. “An amount of Rs10 crore has been withdrawn since the moratorium was imposed,” Manoharan told the media in a conference call on Wednesday.

The shape a new LVB might take

Reason For Moratorium

Reason For Moratorium